Estonia 2040 scenarios

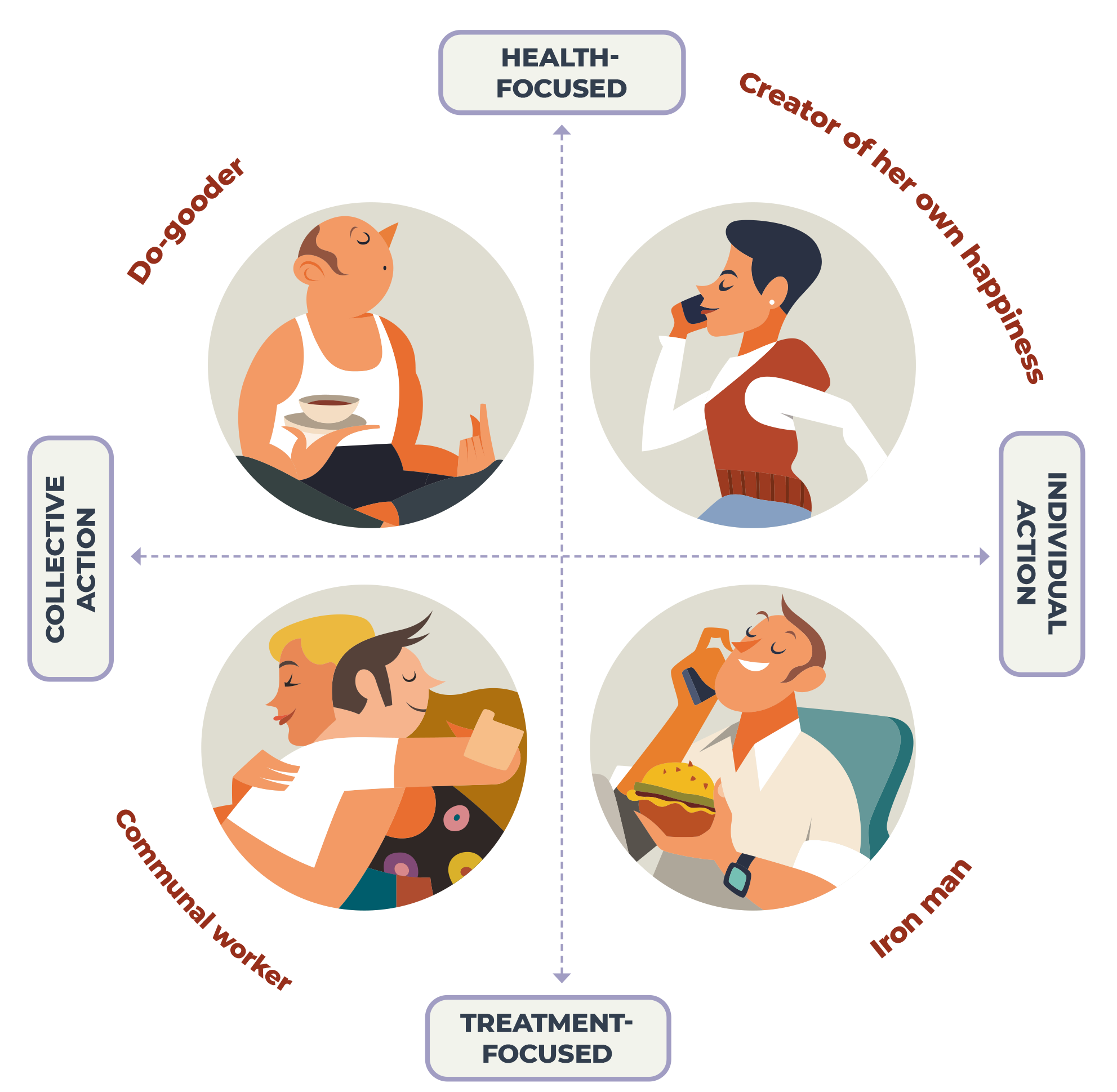

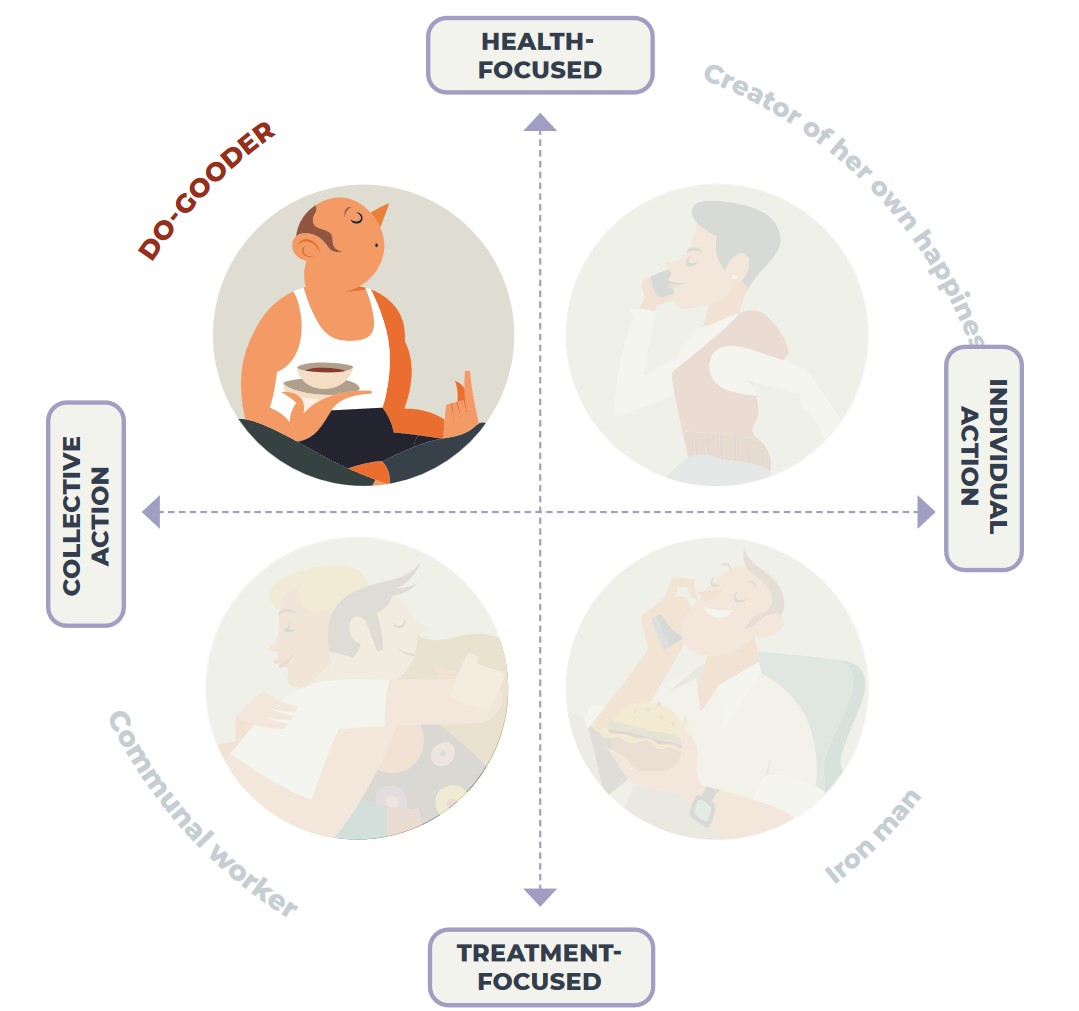

The four exploratory scenarios (Börjeson et al. 2006), illustrating very different possible future developments play out the impact of the main trends described in this chapter. The exploratory scenarios illustrate the possible extremes of each axis, which may not materialise exactly as described here. For example, health care is unlikely to become polarised in such a way that the focus will be solely on prevention or solely on treatment. However, leaning more in one direction or the

other, investing more funds in it or communicating messages supporting it is entirely possible. We selected the axes for the scenarios so as to cover both the wide-ranging changes in social attitudes and health behaviour and developments in the healthcare sector more specifically. Global trends (e.g. climate change or the impact of artificial intelligence and other still-unknown technologies) were included selectively.

The main axes for the future scenarios represent the predominant type of action and the focus of mental health interventions. When the two axes intersect, four scenarios arise. We begin each scenario by outlining the main characteristics of the future story that distinguish it from the others. This is followed by a description of what life is like in this possible future world, based on the two axes. The future stories are illustrative, and the main characters are presented as caricatures, with their key characteristics deliberately exaggerated. In the Estonian version, the main characters of all four scenarios are intended as gender neutral. In English, we address them using ‘she’ in some scenarios and ‘he’ in others, although it could just as well be the other way around. The key factors in each scenario apply equally to both men and women. It goes without saying that none of the scenarios appears in a pure form in real life, and none is good or bad in all its elements.

AXIS 1 – TYPE OF ACTION In a complex society, people’s individual agency and their skills for collective action in various psychosocial environments (family, education and working life) are being put to the test more than ever before. Thus, our first axis focuses on the various ways in which the

awareness and skills supporting mental health and well-being can develop in individuals and their psychosocial environments. One end of the axis represents a focus on individual action, which does not build strong community ties, and the other end represents collective action, which creates new and/or stronger support networks.

AXIS 2 – FOCUS OF MENTAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS Although the prevalence of mental health disorders has increased and is likely to increase further, the availability of specialist care cannot grow indefinitely. The state and local governments have to do more with fewer resources – they have to

find clever ways to strengthen mental health and organise help, including preventive measures to reduce the number of people in need of help. One end of the axis represents a focus on treatment, or dealing with the consequences. The other end represents a focus on health, or reducing the

number of people in need of help with prevention.

Future scenarios

The main characters – Margo, Robin, Kait and Karol – meet in 2040 in a popular cafe in a quiet tree grove in the centre of Tallinn. The gruelling years of crisis, natural disasters, wars, migration and economic recession have had a severe impact on people’s psyches. The government has realised that the medical system cannot cope with the nation’s ever-increasing mental health problems, and it is looking to communities for support. The main characters are active people whose initiative has led to the creation of mental health centres in their communities. These functional models could be widely used in other regions of the country. Today, they must decide which model best supports people’s mental health and well-being and considers society’s values and options as well as people’s attitudes and needs.

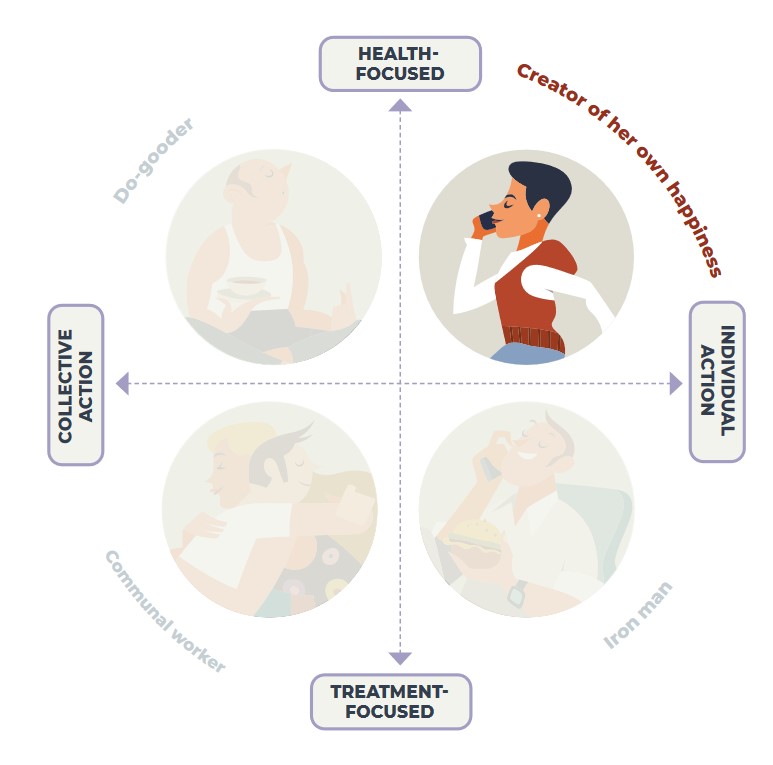

The creator of her own happiness

| Responsibility for mental health | Do it yourself. Acting on your own comes first |

| Maintaining mental health | Maintaining mental health |

| Maintaining mental health | Maintaining mental health |

| Maintaining mental health | Problems are a sign of failure |

| Living environment | Living environment |

| Digital environment | Digital environment |

| Sense of community | Vague. Living alone is preferred |

| Lifestyle | Obsessively healthy |

| Self-care toolbox | Abundant, high awareness |

With a screech of her bicycle tyres, Margo stops in front of the cafe. At the table, she eats homemade salad out of a box, because she knows best what is good for her, and she believes that everybody creates their own happiness.

Margo was a teenager when the world was in lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and her generation adapted to the digital lifestyle quickly. When Margo has a problem with mental health, she looks to ‘Dr Google’ first for answers. For her, the physical world is slow and not very motivating. Pop-up relationships are her only form of close relationship. It is lonely sometimes, but living alone is comfortable.

Margo lives in the heart of the city. ‘Even though, as a result of the green transition, many asphalt lots have been turned into parks in recent years and some Estonians have a garden, not everyone has such options and access to nature,’ says Margo. The quality of housing, the size of living space and the access to green spaces are very different. ‘That is why the primary goal of my mental health centre is reducing stress.’

The centre, located between office buildings, has spacious rooms for exercise, because sports and exercise are the foundations of mental health. The centre has nutritionists and body consultants. Body design has become a form of mass culture, or rather a plague, which sometimes goes to extremes. A community garden surrounds the centre because gardening has scientifically proven benefits for mental health. The centre has a lot of greenery and quiet places. Various digital-based therapies and online counselling are offered.

Margo thinks that a person’s mental health should not be anyone else’s business. ‘People use guidance materials and put together their own mental health journey,’ explains Margo. ‘And if you cannot manage your mental health, it is your personal failure!’ At the centre, people can learn self-care and mental health first-aid techniques and consult with a life coach. These services are expensive, and only the wealthiest people can afford them. It is hard to navigate the wellness industry and mental health gurus out there. Who is for real and who is just an extension of the world of entertainment?

Margo’s motto is: ‘The fishing rods are handed out, but you have to catch the fish yourself.’

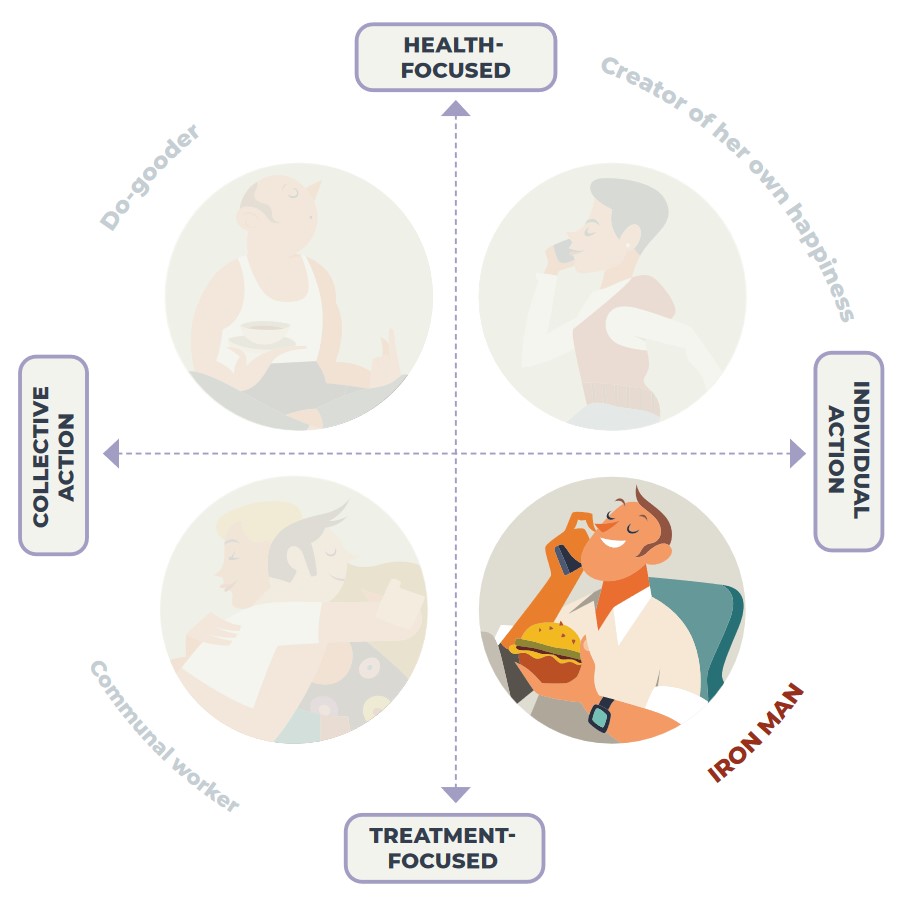

The iron man

| Responsibility for mental health | Do it yourself. Acting on your own comes first |

| Maintaining mental health | Treatment- and services-focused |

| Focus of mental health services | Putting out fires, personalised medicine |

| Mental health problems | Problems are not recognised until they are acute |

| Living environment | Commuting between city and country homes |

| Digital environment | Highly developed, rich in technology |

| Sense of community | Non-existent. Everyone for themselves |

| Lifestyle | Harmful to oneself |

| Self-care toolbox | Not considered valuable or important |

Robin the iron man orders a huge burger and a large mug of strong coffee. His fast-paced life, business projects and events, along with commuting between his city and country home, leave no time to think about self-development or mental health. ‘Everyone fights for themselves,’ he says as he introduces his mental health centre.

In recent decades, society has been thrown from one crisis to another, which has also increased economic instability. There is a great deal of inequality and little social cohesion. Well-being is unstable – constant instability exacerbates mental health problems, but there is not enough time or money to treat them thoroughly. ‘Fires are being put out constantly. People are withdrawn; they almost never share their problems with others. Everyday life requires a lot of attention, and it creates stress. You only go looking for help when you are in deep trouble. Because of all this, creating a network of mental health centres is essential.’ When creating the centre, Robin felt that he might need such a place himself.

The centre is in the middle of the city, so it is easy to visit a psychiatrist or psychologist from your office, even during a lunch break. Numerous pocket parks and small green lots for relaxation surround the building. ‘Most importantly, the centre treats people who come to us with their problems. We rely on the modern possibilities of personalised medicine, and we also use new health technologies that help guide and organise treatment effectively,’ explains Robin.

The centre has a psychologist and a psychiatrist who prescribes pills, as well as babysitters so that parents can rest. ‘We also have life coaches and counsellors. For example, family therapists are in high demand because family relationships are superficial in today’s success-oriented world, different generations do not really communicate with each other, there are many problems in blended families, and so on. Even personal relationships are contractual these days,’ Robin sighs. The centre has many rooms for individual counselling, but most patients prefer remote therapy instead because they usually do not have time to come here.

Since everyone can only rely on themselves, Robin has also invested in individual health insurance. ‘People need to realise that when trouble comes, they have to rely on their own savings,’ Robin concludes.

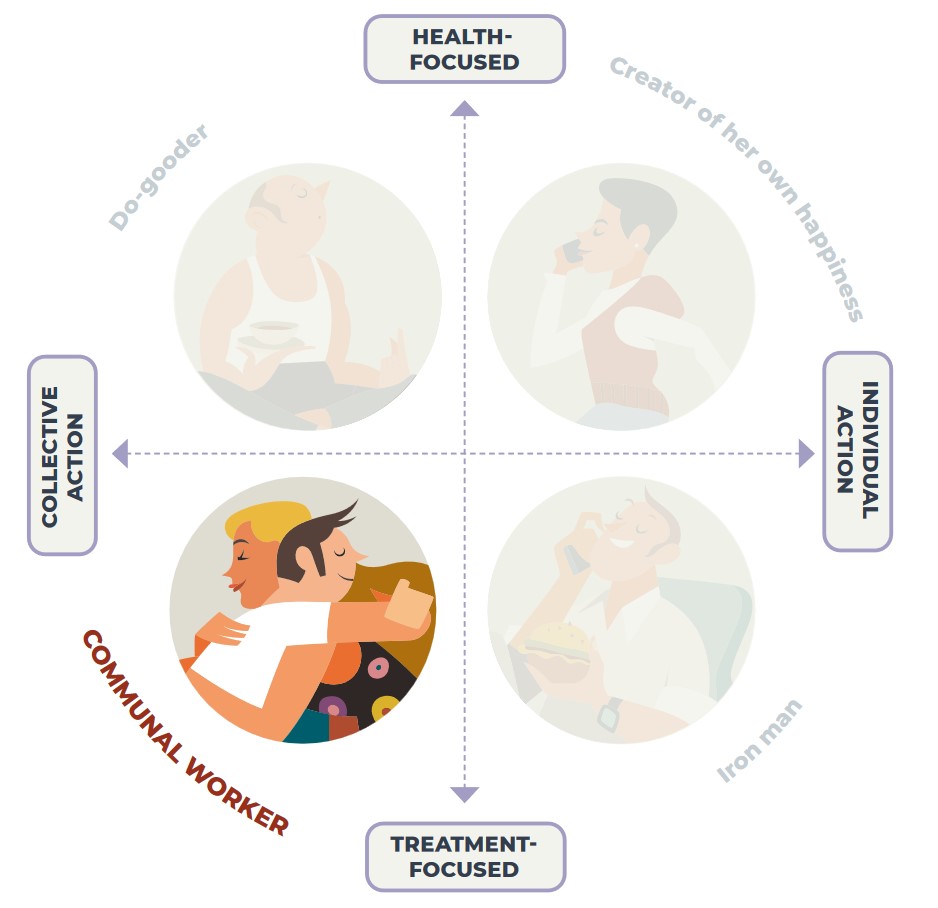

The communal worker

| Responsibility for mental health | Shared and communal. Acting together comes first |

| Maintaining mental health | Community services-focused |

| Focus of mental health services | Problem-oriented community services, abundant options |

| Mental health problems | Problems are dealt with when they arise |

| Living environment | Urban environment with a community garden |

| Digital environment | Rich in technology, tight social networks |

| Sense of community | Warm and welcoming |

| Lifestyle | Taking sufficient care of oneself, environmentally conscious |

| Self-care toolbox | Joint activities and self-care groups are popular |

Kait, in her long and colourful robe, is called the communal worker because she is always busy with this or that much-needed community project. She hugs everyone before taking a seat. Kait orders a berry juice because she knows it is made from berries grown in her friends’ community garden.

In recent years, Estonia’s happiness index has increased, which is attributed to the country’s efforts towards sustainable development and a responsible economy. Society has learned from the crises that an active community is the basis for coping. ‘The best medicine is caring for each other,’ says Kait. She was born when war was raging in Ukraine, and her parents told her that back then, people were careless and critical towards each other. Kait does not want that to be normalised again. She lives in the capital, in a district known for its wooden buildings. She works from home, and robots deliver everything she needs to her.

‘The mental health centre was a joint effort – we raised the funds and built it ourselves! There is no need for state funding. We are managing with crowdfunding.’ The centre is on the premises of an abandoned shopping centre; people do not go shopping much anymore. Kait has been picking herbs and drying berries for the health centre all summer, and in the evenings she manages the various health-related groups on social networks. People in these groups share her views and are the creators, supporters and employees of the mental health centre.

In the centre, special attention is placed on group therapy sessions, where solutions to various problems are sought and which are led by local peer-support counsellors. The centre also organises creative therapy workshops and hikes and has a backyard cafe. All these provide opportunities to socialise. ‘Many people who come to us have phobias and social anxiety,’ the centre’s volunteers say. ‘We do not rule out conventional medicine, but sometimes people are sceptical about mainstream help and digital technologies. People who have personal experience and are well-known or recommended are often trusted more,’ says Kait. The centre boldly experiments with psychedelic therapies, and the community mental health ambulance has worked very well.

Although sometimes the grind makes Kait feel exhausted (she calls it ‘the community work stress’), she says confidently: ‘People contribute to the community and expect to get something in return. The responsibility for ensuring mental health and well-being lies with communities.’

The do-gooder

| Responsibility for mental health | Shared and communal. Acting together comes first |

| Maintaining mental health | Centred around ecology, prevention-focused |

| Focus of mental health services | Community support services |

| Mental health problems | Problems should be prevented but are not to be ashamed of |

| Living environment | Ecovillage on the outskirts of the city |

| Digital environment | Global, integrated into everyday life |

| Sense of community | Tight-knit and supportive |

| Lifestyle | Healthy, natural part of the daily routine |

| Self-care toolbox | Abundant, acquired from a young age |

Karol, known as the do-gooder among his friends, orders green tea and beetroot chips. He lives an hour’s bike ride from the capital, in one of the many ecovillages on the outskirts of the city that became popular after the energy crisis ravaged the world.

‘I interact with people from many different communities, and I know that the major crises and natural disasters of recent years have had a debilitating effect on people’s mental health. For example, people often come to us with concerns about the climate and social phobias. People can find support from their communities, but our centre is focused on prevention. We have lectures and workshops. We also teach self-care techniques, yoga and proper nutrition,’ he says.

Karol, who is retired, does not have a family, because starting a family is no longer a social norm. ‘Our generation has fewer children than pets,’ Karol admits. He has a strong sense of responsibility and is dedicated to repairing the broken world inherited from our ancestors. In the last 20 years, problems with face-to-face communication have reached epidemic proportions. Stress and anxiety disorders caused by isolation are even more common than they were immediately after the COVID-

19 pandemic.

The centre founded by Karol and his partners has done a lot to ensure that the everyday living environment does not cause stress. Far from the din of the city, the centre is not affected by noise or light pollution, which is why it is favoured by patients with sleep disorders. As a sign of an ageing society, many of the centre’s clients are older people. ‘We help a lot of older people who feel lonely. We create bridges between generations. Older people can teach the youth good old-fashioned communication skills, such as making eye contact and reading body language.’

Prevention campaigns and including self-care classes in school curricula have paid off: taking care of mental health has become a natural part of personal hygiene. People are aware of different support services. The state mainly allocates funds only to mental health support services because most of the prevention and support services are borne by the communities. People do not need to pay for community support services.

The private sector also contributes significantly to prevention because responsible and social entrepreneurship is seen as natural in society. More and more reasonably priced creative products that promote mental health are brought to the market.