The labour market, the working environment, and mental health and well-being

Work is an essential part of an adult’s life, affecting their economic, cultural, social and psychological coping abilities.

Working takes up a large part of a person’s time, and the working hours often cannot be freely chosen. According to Eurostat (2022), in 2021, the average working week in Estonia was 39 hours for men and 36 hours for women, while 21% of men and 15% of women had the benefit of flexible working hours. Compared to being away from the labour market for various reasons (e.g. unemployment, parental leave), working as such is associated with a greater sense of well-being. Work is an important source of self-development and self-determination and has a wider positive impact on well-being, because work provides social connectedness. However, there are a number of risks in the working environment and the organisation of work that affect well-being and mental health.

Working often requires physical and mental, as well as emotional, effort. The nature of work and working conditions are important for both the worker and their family members. Harvey et al. (2017) divide the work-related risk factors for well-being into three groups: imbalanced job design (e.g. working time is not enough to fulfil work tasks, effort-reward imbalance), occupational uncertainty (e.g. temporary work) and a lack of value and respect in the workplace (e.g. a low level of autonomy at work, i.e. unfair treatment or bullying and the exclusion of employees from decision-making). Eurostat (2021) ), 41% of women and 34% of men in Estonia considered their working environment harmful to their mental health in 2020, while 48% of respondents reported that health problems arising from work affect their daily activities. The main causes of stress were high workload, time pressure, and interaction with difficult colleagues and clients. A survey conducted in Estonia in 2020 (Eurofound 2020) showed that people also worry about a lack of savings and possible hardships in the event that they or a family member loses their job.

How one copes with work in times of rapid and unexpected changes, and how this affects mental health and well-being, depends not only on the person but also on factors such as the workplace, working conditions, family-related factors, and opportunities to reconcile work and family life. Recent international studies show that the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which strongly shook the entire occupational sphere, has not been uniform across the entire population. Women, young people, frontline workers, and the infected and people close to them, as well as people who isolated themselves completely, suffered more mental health problems (Reile et al. 2021).

The purpose of this article is to show how the mental health and well-being of Estonian employees coming from different socioeconomic groups and working under different conditions has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic and how these changes are related to differences in working environments vis-à-vis other European countries.

For Estonia, the COVID-19 crisis that began in 2020 was unprecedented, giving rise to a state of emergency, excess mortality, an overload in the hospital system, and restrictions on movement and activities. There were also major changes in the usual working environments and working conditions. Many studies (nt Kumar and Nayar 2021) have confirmed the negative impact of the pandemic on people’s mental health and well-being, including through changes in working conditions.

The pandemic has significantly changed the forms and ways of working for some people and threatened job stability for others, causing issues with coping and self-identification. The labour market impacts of the pandemic are more wide-ranging than just the absence of certain workers from work or the reduction or increase of workloads during the crisis. Changes in the organisation of work affect the types of workers participating in the labour market. The organisation of work and the workers’ mental health affect work performance, which in turn affects the workers’ income and success in the labour market. Changes in the organisation of work and workload ultimately affect mental health.

SHARE OF REMOTE WORK DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The pandemic accelerated changes in the ways, times and places of working. The number of people involved in platform work and especially remote work increased. In the EU, the share of people working from home increased from 5% in 2019 to 12% in 2020. According to Statistics Estonia, the share of employees in remote work was 9% in 2015 and 18% in 2019; it reached 31% in 2020. Most of them worked from home for all their working hours, while 11–15% worked from home for only a small fraction of the working time. By the beginning of 2021, the share of remote working had dropped to 21%.

The increase in remote working during the pandemic required both employees and managers to be able to implement and coordinate hybrid forms of work despite having no previous experience or norms for doing so. During the pandemic, the share of employment relations based on civil law contracts rather than employment contracts increased.

In connection with remote working, employees felt changes in both their mental and physical health, which prompted greater public attention to the issue of employees’ well-being. According to the Eurofound(2020) survey, 3–4% of respondents stated that remote work caused them stress, and 12% attributed the stress to an increased workload. According to the same survey, overall life satisfaction in Estonia, on a 10-point scale, decreased from 6.8 points in 2019 to 6.0 points in 2021. The decrease was somewhat more for men than for women. With the expansion of flexible forms of work, the need for additional competencies grew. ICT knowledge, risk management and analysis, product development, communication and management skills became more important. Everyone’s self-management skills, including the ability to independently plan and organise their work and take responsibility, became important. Employees became more aware of the significant impact of the working environment on their mental health.

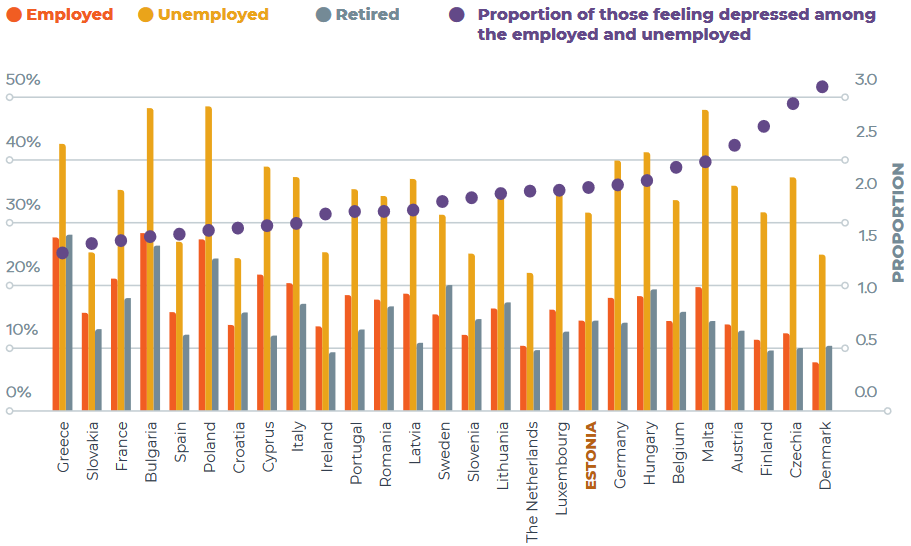

Employment as such can have a beneficial effect on mental health. The 2020 Eurofound survey reveals that the percentage of people who have experienced depression is more than twice as high among people who are unemployed than among those who are employed.

The respective figures for Estonia are 33% among the unemployed and 15% among the employed (Figure 3.4.1). Compared with other European countries, Estonia falls in the middle range in terms of the difference in the percentage of people who felt depressed during the previous week among the unemployed compared to the employed.

A new aspect of work during the COVID-19 pandemic was the fact that many people were working from home. The Eurofound 2020 survey shows that in Estonia the proportion of those who were depressed most of the time in the previous two weeks did not differ significantly between those who worked from home (including those who had already been working from home before the pandemic) and those who did not work from home (Figure 3.4.2).

However, it seems that the change in work organisation due to remote working has slightly increased the proportion of depressed people. This may be due to the fact that they may not have had the necessary tools or space to work from home, or they may have lacked the skills to do so (e.g. using video meeting tools) or were unable to get immediate help from colleagues when it was needed (Ainsaar et al. 2021). In addition, Estonia stands out among European countries in that it had a large share of depressed people among those who did not have the opportunity to work from home. A direct risk of infection makes them a vulnerable group.

J3.4.2.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-13

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J342=read.csv("PT3-T3.4-J3.4.2.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J342$X[4]="ESTONIA"

names(J342)=gsub("\\.", " ", names(J342))

levels=reorder(J342$X,J342$`Neither previously nor during the pandemic`)

J342=pivot_longer(J342,2:5)

J342$X=as.factor(J342$X)

J342$X=factor(J342$X,levels)

J342$name=as.factor(J342$name)

J342$name=factor(J342$name,levels(J342$name)[order(c(4,2,1,3))])

font=rep(1,27)

font[4]=2

#joonis

ggplot(J342)+

geom_col(aes(x=X,y=value,fill=name),pos=position_dodge(0.7),width=0.7)+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#634988","#6666CC","#bf6900","#f09d00"))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90,face=font))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

theme(legend.title = element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")## Warning: Vectorized input to `element_text()` is not officially supported.

## ℹ Results may be unexpected or may change in future versions of ggplot2.For many people, the pandemic led to changes in workload. There were those who suffered from a sudden increase in workload due to additional tasks related to the pandemic (e.g. frontline workers and managers dealing with crisis management and the coordination of frontline workers). However, there were also those whose workload decreased (e.g. people working in the service sector). Depression was widespread in Estonia, as well as in the majority of other European countries. This was especially noticeable among those whose workload decreased significantly during the pandemic (Figure 3.4.3), , so that having a job no longer gave them the customary sense of security.

J3.4.3.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-13

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J343=read.csv("PT3-T3.4-J3.4.3.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J343$X[8]="ESTONIA"

names(J343)=gsub("\\.", " ", names(J343))

levels=reorder(J343$X,J343$`Decreased a lot`)

J343=pivot_longer(J343,2:6)

J343$X=as.factor(J343$X)

J343$X=factor(J343$X,levels)

J343$name=as.factor(J343$name)

J343$name=factor(J343$name,levels(J343$name)[order(c(3,1,2,5,4))])

font=rep(1,27)

font[8]=2

#joonis

ggplot(J343)+

geom_col(aes(x=X,y=value,fill=name),pos=position_dodge(0.7),width=0.7)+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#6666CC","#38bf7b","#668080","#f09d00","#bf6900"))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90,face=font))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

theme(legend.title = element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")## Warning: Vectorized input to `element_text()` is not officially supported.

## ℹ Results may be unexpected or may change in future versions of ggplot2.There was basically no time off work. When I went out of the house for the first time, I went to visit my sister. I think that by then, more than a month had already passed, or maybe one and a half months – it was quite a long time. There wasn’t like… While others shared on social media how they were able to look inside themselves, so to speak, and watch Netflix and read and enjoy the outdoors, we on the crisis team were in a completely different situation.

Figure 3.4.4 also shows that having a job is very clearly related to mental health, apparently through financial security. The figure shows that the share of depressed people in Estonia was highest among those who lost their jobs either temporarily or permanently. Nevertheless, among those who permanently lost their jobs, there were more depressed people in most other European countries than in Estonia.

J3.4.4.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-12

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J344=read.csv("PT3-T3.4-J3.4.4.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J344$Riik[3]="ESTONIA"

names(J344)=gsub("\\..", ", ", names(J344))

levels=reorder(J344$Riik,J344$`Yes, permanently`)## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NA

## Warning in mean.default(X[[i]], ...): argument is not numeric or logical:

## returning NAJ344=pivot_longer(J344,2:4)

J344$value=as.numeric(gsub("%", "", J344$value))

J344$Riik=as.factor(J344$Riik)

J344$Riik=factor(J344$Riik,levels)

J344$name=as.factor(J344$name)

J344$name=factor(J344$name,levels(J344$name)[order(c(3,2,1))])

font=rep(1,27)

font[3]=2

#joonis

ggplot(J344)+

geom_col(aes(x=Riik,y=value,fill=name),pos=position_dodge(0.8),width=0.7)+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#6666cc","#FF3600","#668080"))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90,face=font))+

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(0,60,10))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

theme(legend.title = element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")## Warning: Vectorized input to `element_text()` is not officially supported.

## ℹ Results may be unexpected or may change in future versions of ggplot2.The impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis on mental health are greater among the non-working working-age population

Since 2008, a survey of the health behaviour of the Estonian adult population has been conducted every two years among people aged 16–64. The total sample size from 2008 to 2020 was over 19,000 individuals, of whom just over 1,000 completed the questionnaire during the first wave of the pandemic, from 12 March to 17 May 2020. The state of emergency in Estonia was not as severe as in more densely populated regions of the world, but it still amplified people’s fears and emotional vulnerability. The survey showed that during the first wave of COVID-19, there was an increase in feelings of depression and sleep disorders, as well as the use of sleeping pills, sedatives and antidepressants among people belonging to different socioeconomic groups. The increase in tension and depression during this period was felt the most among the working-age population in Estonia. The survey also revealed that persons participating in the labour market have significantly fewer mental health concerns than persons who are not participating in the labour market (those who are inactive, unemployed, on parental leave, studying or in military service). This finding is in line with the trends in other countries (Figure 3.4.5, cf. Figure 3.4.1).

J3.4.5.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-12

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J345=read.csv("PT3-T3.4-J3.4.5.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J345)=gsub("\\.", " ", names(J345))

names(J345)[2]="Anxiety, depression"

J345=pivot_longer(J345,2:8)

J345$name=as.factor(J345$name)

J345$name=factor(J345$name,levels(J345$name)[order(c(6,1,3,4,7,5,2))])

J345$X=as.factor(J345$X)

J345$X=factor(J345$X,levels(J345$X)[order(c(2,1))])

#joonis

ggplot(J345)+

geom_col(aes(x=name,y=value,fill=X),pos=position_dodge(0.8),width=0.7)+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#6666cc","#38bf7b"),breaks=c("Without work","Participating in the labour market"))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

coord_flip()+

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(0,60,10))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

theme(legend.title = element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")The impacts of the health crisis manifested themselves differently in different groups. Some population groups may have benefitted from social isolation, for example, by having more flexible working hours and spending less time commuting. According to the analysis, managers, above-average salary earners, men and people in a couple relationship benefitted from the lockdown, as these groups reported less anxiety and sleep problems than in previous periods. On the other hand, women, workers in technical jobs (including nurses), workers in the tourism and service fields, and people with lower salaries experienced more mental health problems during the state of emergency at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic than they had in previous years.

The conditions of the working environment have varied effects on the mental health and well-being of different groups of employees

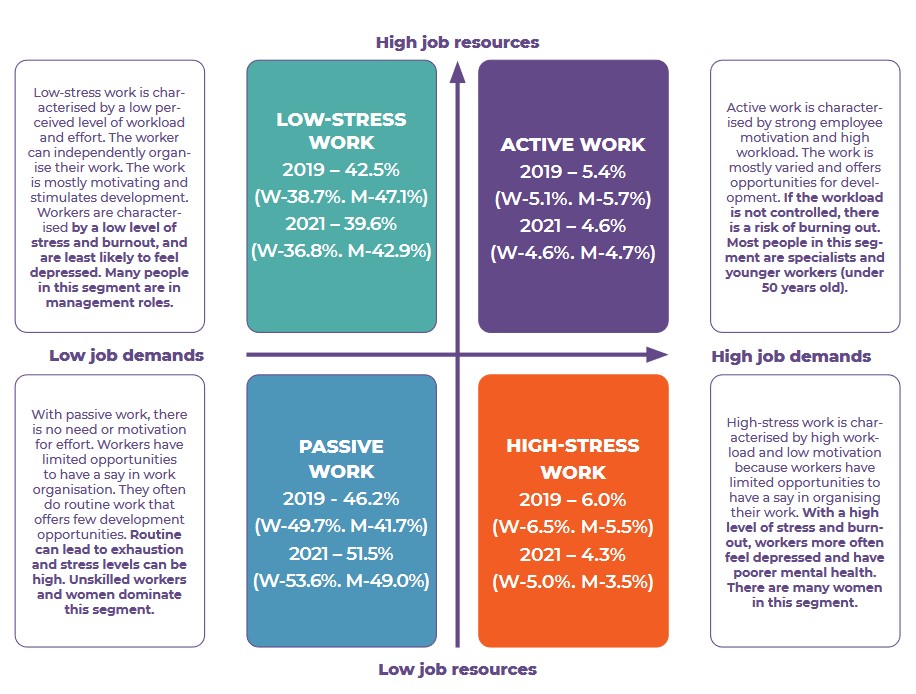

The quality of the working environment and its impact on employees’ well-being can be assessed in terms of the job demands on the employees and the job resources available to them. The balance of job demands and resources is expressed in how complex, varied and intensive the work is, what opportunities it offers for personal and professional development, and the extent to which the employee can have a say in matters concerning their work and organise their activities independently.

In 2019, TalTech and Qvalitas Arstikeskus AS began a study to assess the psychosocial quality of the working environment, using the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire COPSOQ III1. The sample consisted of employed people visiting Qvalitas clinics for occupational health checks. The data collected from nearly 26,000 respondents in 2019 and 2021 are used below to compare pre-pandemic and post-pandemic assessments of people’s working environment and well-being.

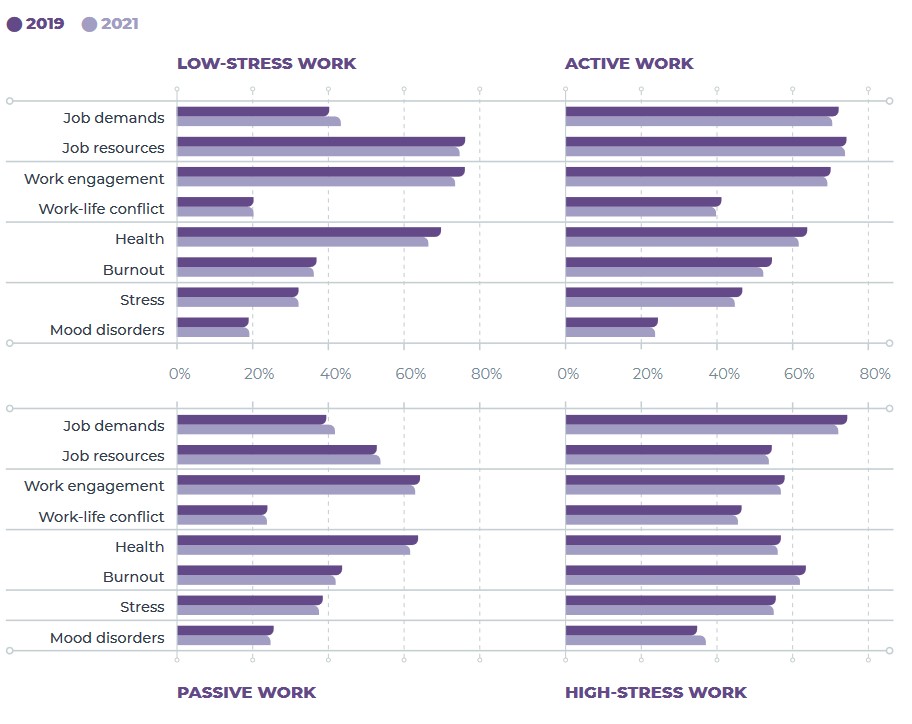

For a more general assessment of the nature of work, we used the job demands and resources model created by Bakker and Demerout (2007) ,which gives insight into employees’ work motivation and performance and helps predict their work stress and burnout (Figure 3.4.6).

Job demands are the physical, cognitive and emotional factors of the working environment which are associated with tension and stress. These have a negative impact on the employee’s mental and physical health, reduce work engagement and productivity, and increase the risk of burnout. Job resources are the physical, social and organisational factors related to work motivation helping employees to achieve goals, increase well-being, reduce stress, and deepen their engagement with their work and the organisation. Employees with high levels of job resources can cope with their daily job demands significantly better and also have potentially lower levels of stress.

Different types of work have different effects on the employees’ mental and physical health, as well as motivation and engagement. Therefore, it is important to know how employees perceive their work. Four types of work can be distinguished based on different combinations of job demands and resources: passive, active, low-stress and high-stress work. The survey revealed that in a two-year comparison, the share of those who perceived their job as low-stress decreased by nearly 3 percentage points, while the number of people in passive jobs increased by 5 percentage points. These two types of work are also the most widely represented. A considerably smaller percentage of respondents rated their jobs as active or high-stress. The share of people in high-stress jobs decreased by approximately 2 percentage points during the period. Changes in the share of people in active jobs were less than one percentage point (Figure 3.4.6). The changes in the two-year comparison are small, suggesting that working during the pandemic did not significantly change people’s perceptions of their jobs.

well-being, including fewer sleep problems and feelings of fatigue. However, flexible work arrangements require considerable self-discipline from the employee.

Low-stress work and active work are most conducive to employee well-being. These types of work involve higher job resources; employee well-being and work motivation are likely to be the highest, regardless of the job demands. High-stress work has a different effect on employees’ mental health than passive work does. In high-stress jobs, the workload often requires great effort and self-control, while independence, involvement and opportunities for development are limited. Passive work often consists of simple and routine tasks, with limited opportunities for development and little independence or involvement in decision-making.

There were significant differences in how men and women assessed the types of work they do. The share of women doing low-stress work is significantly smaller than the share of men, while women more frequently report doing passive or high-stress work. Women rated their job demands higher than men, feeling that their work pace was faster and workload higher than they would like. More women are engaged in both mentally and physically taxing work, and there are fewer women among employees whose work is varied and motivating and stimulates development.

rience more mood disorders than men do.

The greater representation of women in passive and high-stress jobs is related to their higher levels of stress and burnout. Women also experience more mood disorders than men do.

There were also differences between job positions (Figure 3.4.7). Among specialists, 40% of respondents were in passive and low-stress jobs. Around 5% of specialists were in high-stress jobs, while specialists formed the largest group among the people in high-stress jobs. They rated their work as varied but found the pace of work fast and the workload high. They also had little say in work organisation matters and time planning.

J3.4.7.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-12

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J347=read.csv2("PT3-T3.4-J3.4.7.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J347)=gsub("\\.", ", ", names(J347))

J347=pivot_longer(J347,2:5)

J347$value=as.numeric(J347$value)

J347$name=as.factor(J347$name)

J347$name=factor(J347$name,levels(J347$name)[order(c(2,4,3,1))])

J347$Tööliik=as.factor(J347$Tööliik)

J347$Tööliik=factor(J347$Tööliik,levels(J347$Tööliik)[order(c(2,4,1,3))])

#joonis

ggplot(J347)+

geom_col(aes(x=name,y=value,fill=Tööliik),pos=position_dodge(0.8),width=0.7)+

facet_grid(~Aasta)+

coord_flip()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#6666cc","#668080","#81DBFE","#38bf7b"),breaks=c("Passive work","Low-stress work","Active work","High-stress work"))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(0,80,10))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

theme(legend.title = element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")More than 70% of unskilled workers perceived their jobs as routine, offering little variety and opportunities for development, as is characteristic of passive jobs. They had very little say in matters of work organisation and time planning, and they lacked flexibility in terms of working time and place. The smallest proportion of these workers were in active jobs. The proportion of unskilled workers who rated their job as high-stress increased during the pandemic. During this period, many of the unskilled workers were frontline workers, whose work became more stressful due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

About 60% of managers rated their work as low-stress, their job demands as moderate or low, and their job resources as high. This means that their jobs are varied and offer opportunities for development, and they can organise their work and time use independently. By being able to organise their tasks and plan their time, the employee can distribute their workload and adjust their work pace. Jobs of this type are versatile and motivating, as well as the most beneficial for mental and physical health.

In 2019, there were more people in high-stress jobs among managers than in other positions: 9% of mid-level and top-level managers rated their work as high-stress and their mental and physical health worse than other employees. By 2021, the proportion of those in high-stress jobs decreased to 6% among mid-level managers and to 3% among top-level managers.

As seen in Figure 3.4.8, employees in high-stress jobs had the worst mental health indicators in both 2019 and 2020. They reported having moderate stress and burnout, as well as a higher rate of occurrence of mood disorders than others. They also rated the degree of work-life conflict as moderate, and their work engagement somewhat lower than representatives of other types of work. Those in high-stress jobs are at risk of transferring the tensions arising at work to their family life, which can worsen their mental health.

The situation is similar with people in active jobs. Their mental health indicators are somewhat better but also indicate moderate levels of stress and burnout. In contrast to people in high-stress jobs, they have fewer mood disorders and their subjective assessment of their health is higher. They have a moderate level of work-life conflict, although their work engagement is very high. People in active jobs usually have the highest work motivation and satisfaction with personal and professional development.

The mental health indicators of those in passive jobs continue to border on critical levels, reflecting a moderate level of burnout and a critical stress level. Their level of mood disorders is low and similar to those in active jobs. The level of work-life conflict is also low, which allows us to assume that tensions arising at work do not necessarily disturb family life.

Those in low-stress jobs have the best mental health indicators. Their stress and burnout indicators are below critical levels. Their subjective assessment of their health is higher than that of people doing other types of work. They have the lowest mood disorder and work-life conflict indicators out of respondents in any category of jobs. Their mental health is good and their work engagement indicators are very high, which suggests that people in this type of job can enjoy both their work and their family life.

In a two-year comparison, people doing all types of work subjectively assessed their health as having worsened somewhat, while mental health indicators improved. The exception is people in high-stress jobs, whose mood disorder indicators somewhat increased. At the same time, all the differences are marginal, and their discriminatory power is weak. The results allow us to assume that the mental health of employees is primarily influenced by the type of job they have and less by external events.

In a qualitative study on mental health and COVID-19, interviews were conducted with frontline workers, parents and older people in November and December 2020 (Ainsaar et al. 2021). The study shows that for many employees, both the working time and the pace of work increased because, especially for managers and frontline workers, urgent tasks were added to their regular tasks and unexpected events occurred often. The continuously changing information and the overload caused by being constantly available through various communication channels (e.g. telephone, email, Skype, Messenger and Zoom) added stress for managers.

I was only able to [work] on weekends. It is not realistically possible to instruct primary school children at home and work at the same time. So, when the school day ends, the work day only begins, and it lasts until midnight if you actually have to get anything done. It would have been different only if the workload had not been so big at that moment and I could have somehow managed it in less time. Well, during the day I managed to answer some emails but not to do any kind of thorough, time-consuming things that require concentration and silence and so on.

The interviews revealed that flexible working time and place can lead to additional stress due to the context (e.g. working from home). When working from home, people may not have enough opportunities to be isolated from other family members, or work tools may have to be shared. If there are primary school children at home who need help with schoolwork, the mother’s working hours are especially fragmented and tend to shift to sleep time. During the pandemic, traditional gender roles were reinforced, which increased stress levels, especially among mothers working from home. While their home- and work-related roles were previously separated in time and place, role conflicts now emerged as both roles had to be fulfilled simultaneously, contributing to psychological tension. Also, women with school-age children had to take on the role of a home teacher, which further intensified the role conflict. Those who did not have children found themselves working all the time. Thus, there were several reasons for the time shortage stress: problems related to juggling work and family life, especially for women, on the one hand, and the intensification of work on the other. At the same time, mothers learned to plan time in a new way, making use of all the available gaps (such as children’s sleep time). They began to set boundaries between work and free time and to review the expectations arising from the job. Paradoxically, remote workers learned to enjoy and value what they used to take for granted, such as working in an office (and being able to focus only on work) and having schools and kindergartens available for children.

Just going to the office has an entirely therapeutic effect at times – imagine that there is silence, you take your coffee and you just work. When I went to the office at some point, even if it was after lunch, it had such a ‘wow!’ effect – I can just work here without anyone interfering. What a luxury! Before then, going to the office and working there just seemed like a routine.

That’s the way things are. You can appreciate ordinary things much more, like being able to go to the gym or, wow, I’m here in the office and I can work in silence. Yes, it doesn’t relate to the scale; rather, I think that the whole state of emergency and the current situation has also taught me a lot, to be grateful for things that otherwise seemed to be taken for granted. I think this is the positive side of this whole thing. To believe, to believe, to appreciate things that you otherwise took for granted.

Thus, as the crisis unfolded, people learned to cope with increased stress and tension in a number of different ways. They began to consciously take time for themselves (art, crafts, reading) and left for places with limited access (such as a summer house). Discussing problems with colleagues using different communication tools, but also limiting communication channels, helped people to cope professionally.

Various studies (including Estonian studies on creative workers in the research and development sector) suggest that enabling flexible working hours and remote working is generally positively correlated with work performance and employees’ subjective well-being, including fewer sleep problems and feelings of fatigue.

many new urgent tasks, and to those whose workload was significantly reduced during the pandemic.

Offering flexible forms of work also often means improved competitive advantages for the employer, as the human resources are used more optimally. However, flexible work arrangements require considerable self-discipline from the employee, who must take control of not only the time of starting work but also the time of finishing work and balance the activities and goals of work and private life.

Summary

Several changes have occurred in the mental health of Estonian people due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Working people continue to have a higher level of subjective well-being compared to non-working people. Our analysis shows that among the workforce, special attention should be paid to women who have children in primary school, to workers for whom the pandemic brought many new urgent tasks, and to those whose workload was significantly reduced during the pandemic. Attention should also be paid to frontline workers and those who lost their jobs due to the pandemic.

In broader terms, the starting points for a redistribution of labour market advantages can be seen in the pandemic-related changes in working life. People who functioned best in a labour market with fixed working hours, working in a workplace and having a stable working life may now be at a disadvantage vis-à-vis those who perform best with flexible working hours and remote working and who can better adapt to and cope with mental health challenges in changing circumstances that require high self-discipline. It is important to understand that the differences between people in terms of these advantages are formed through the combined effects of both natural (including genetic) factors and factors arising from the living and developmental environment. Some of these factors are under the person’s control, while others are not. This means that it is crucial to take into account the individual characteristics of people both in the organisation of work at the employer’s level as well as in the design of labour market measures on the national level. More attention should be paid to ensuring different but equal opportunities for different groups of the working-age population (e.g. working mothers with young children, the unemployed and those whose workload was considerably reduced during the pandemic) to ensure their optimal involvement in the labour market and their work contribution and to improve their subjective well-being.

Overall, people learned new coping mechanisms (time management, choice of communication channels, taking time off and physical separation) due to new situations of tension and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. More important than salary is a sense of belonging and security and the opportunity to take time for self-realisation, which also supports mental health.

mental health.

The COVID-19 pandemic era has rapidly provided new solutions to enable various social groups to work more flexibly and for management to trust employees to work remotely. Such solutions include flexible options to switch between working from home and in the office, and the development and widespread use of online collaboration tools.

Ainsaar, M., Bruns, J., Maasing, H., Müürsoo, A., Nahkur, O., Roots, A. ja Tiitus, L. (2021). Vaimne tervis, seda mõjutavad asjaolud ja toimetuleku strateegiad lastega perede, eakate ja eesliinitöötajate näitel Eestis 2020-2021. Tartu Ülikool. https://sise.etis.ee/File/DownloadPublic/06a7047f-befb-4bc4-806f-97ea58055c3b?type=application%2Fpdf&name=Vaimne%20tervis_loppraport.pdf&fbclid=IwAR3UWavyONes9s-G7viUnObY-m5XvAz32EGY1uEELNCvczn2nawxFyhvrhc

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328.

Eurofound (2020) Industrial relations and social dialogue Estonia: Working life in the COVID-19 pandemic 2020. https://euagenda.eu/upload/publications/wpef21013.pdf (vaadatud 16.05.2022)

Eurostat (2022) Average number of actual weekly hours of work in main job, by sex, age, professional status, full-time/part-time and economic activity (from 2008 onwards, NACE Rev. 2). Eurostati koduleht. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFSQ_EWHAN2__custom_2671904/default/table?lang=en (Vaadatud 13.05.2022)

Eurostat (2021) Self-reported work-related health problems and risk factors – key statistics. Eurostati koduleht. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Self-reported_work-related_health_problems_and_risk_factors_-_key_statistics#Exposure_to_mental_risk_factors_at_work (vaadatud 13.05.2022)

Harvey, S. B., Modini, M., Joyce, S., Milligan-Saville, J. S., Tan, L., Mykletun, A., Bryant, R. A., Christensen, H., & Mitchell, P. B. (2017). Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 74(4), 301–310.

ILO. (2016). Workplace stress: A collective challenge. Labour Administration, Labour Inspection and Occupational Safety and Health.

Kumar, A., & Nayar, K. R. (2021). COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health, 30(1), 1–2.

Leka, S., Jain, A., & Organization, W. H. (2010). Health impact of psychosocial hazards at work: An overview. World Health Organization.

Reile, R., Kullamaa, L., Hallik, R., Innos, K., Kukk, M., Laidra, K., Nurk, E., Tamson, M., & Vorobjov, S. (2021). Perceived Stress During the First Wave of COVID-19 Outbreak: Results From Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in Estonia, Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1-6.