Stress and coping with it: the COVID-19 pandemic in Estonia

All living things have to cope with environmental changes and respond to challenges in order to survive. Every now and then, the quantity or difficulty of these trials can become too much and trigger a state of emotional tension or stress. Accumulating stress and unsuccessful attempts to tackle it can have a strong negative effect on wellbeing and mental health. or example, the COVID-19 pandemic, with its health risks, uncertainty, restrictions and other stressors, raised stress levels for many Estonians.

This article looks at the perceived stress levels among the Estonian population, including their changes both in the long term and in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. We will also present strategies that help people cope better with stress and reduce its negative effects.

There are many ways to assess stress and the ability to cope with it. In this article, we will rely on self-reported indicators of perceived stress from population-based studies. A self-report questionnaire is a convenient and valid tool for assessing the prevalence of stress, since the activation of a stress response depends in large part on how people perceive situations and stimuli (Roddenberry and Renk 2010).

More specifically, we will use data from the Health Behaviour among the Estonian Adult Population survey, which has been conducted every two years since 1990; the Estonian Biobank Mental Health Online Survey conducted in the spring of 2021 by the Estonian Genome Centre at the University of Tartu; the 2021–2022 Estonian National Mental Health Study; and the population-based survey Awareness of COVID-19 and Related Attitudes in Estonia (a COVID-19 rapid survey), conducted by the National Institute for Health Development in 2020–2021

Stress is the body’s natural response to environmental changes and challenges. The word ‘stress’ can have slightly different meanings in different contexts, but

here we use it to describe a relatively constant state of mental and physical tension that has been triggered in response to a perceived threat. The same definition is reflected in the questions that respondents are usually asked in self-report surveys measuring stress levels: “Have you been stressed, under pressure?” and “Considering everything that is going on in your life, how much stress have you experienced lately?“.

Stress is generally caused by the interaction of three components:

- a stressor, i.e. a potentially dangerous stimulus in the organism’s internal or external environment;

- perceiving the stimulus as exceeding the available coping resources;

- a physiological and emotional response that mobilises resources to cope with the stressor.

Any change in the internal or external environment of an organism that can disturb its equilibrium can become a stressor (Selye 1976). In a narrower sense, this disturbance is caused by stressors that disrupt the body’s homeostatic equilibrium (defined as an appropriate range of temperature, fluid content or nutrients). In a broader sense, it is caused by stressors that threaten the achievement of a psychological goal, such as a short deadline for a work assignment, an important exam, or the fear of contracting COVID.

While environmental stressors are necessary for stress to occur, they alone do not trigger stress. The same situation – for example, self-isolation due to COVID – may cause stress in one person but not in another. This difference is due to the second component of stress, i.e. perceiving the stressor as exceeding available coping resources. Here, coping resources can be not only opportunities or skills but also various aids and people to turn to for help. Resources that help people cope with self-isolation, for example, include the possibility to work remotely and having time management skills. Therefore, a stressor triggers a stress response when the individual feels that the stressor poses a significant threat to them and that they lack the resources to cope with the stressor and keep the situation under control (Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

When perceived as a demand that exceeds available resources, the stressor triggers a series of interrelated changes in the body and mind. here are two main bodily systems that respond to it: the sympathetic nervous system1 and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis2. Together, they produce wide-ranging changes throughout the body, increasing the heart rate and respiratory rate, raising blood pressure and blood sugar levels and increasing blood flow to the muscles, liver and brain. These changes aim to help the body mobilise itself in order to cope effectively with the encountered stressor.

A physical stress response is usually accompanied by mental changes. On the one hand, there is a sense of what people describe as unpleasant tension, worry and also stress. On the other hand, stress directs attention and other cognitive resources to processing information related to the situation. Just as the physical stress response helps the body prepare for exertion, mental changes related to stress help the mind to cope with the challenge being faced. As an unpleasant feeling, stress drives people to take action to relieve the tension they are experiencing. Investing cognitive resources increases the likelihood of that action having an effect.

Behaviours that are driven and amplified by the stress response are often effective, and as a result, the problem is resolved more quickly than under normal circumstances. Where such behaviour is ineffective, however, the person may experience a prolonged state of stress. A long-term or chronic stress response strains the body and increases susceptibility to various physical and mental illnesses.

In the Health Behaviour among Estonian Adult Population survey, perceived stress is assessed with a single question: “In the last 30 days, have you been stressed, under pressure?”. Figure 1.2.1. shows the prevalence of unbearable or higher-than-average stress levels based on the answers to this question, with 95% confidence intervals, among Estonian residents aged 16–64 in the period from 1990 to 2020.

J1.2.1.R

maiko.koort

2023-06-19

library(tidyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(scales)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J121=read.csv2("PT1-T1.2-J1.2.1.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J121)[2:17]=sub("X","",names(J121))[2:17]

J121d=J121[1:2,]

J121d=pivot_longer(J121d,col=names(J121)[2:17],"Year")

J121d$Aasta=as.factor(J121d$Year)

J121e=J121[3:6,]

J121e=pivot_longer(J121e,col=names(J121)[2:17],"Year")

J121d$Upper=numeric(32)

J121d$Lower=numeric(32)

J121d$Upper[1:16]=J121e$value[17:32]

J121d$Lower[1:16]=J121e$value[1:16]

J121d$Upper[17:32]=J121e$value[49:64]

J121d$Lower[17:32]=J121e$value[33:48]

J121d$value=as.numeric(J121d$value)

J121d$Lower=as.numeric(J121d$Lower)

J121d$Upper=as.numeric(J121d$Upper)

#joonis

ggplot(J121d)+

geom_point(aes(x=Year,y=value,group=X,col=X),pos=position_dodge(0.2))+

geom_line(aes(x=Year,y=value,group=X,col=X),pos=position_dodge(0.2),linewidth=1.5)+

geom_errorbar(aes(x=Year,ymin=Lower,ymax=Upper,col=X),pos=position_dodge(0.2),width=0.3)+

theme_minimal()+

scale_color_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#FF3600"))+

ylab("%")+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,35))+

theme(legend.title=element_blank(),legend.position = "bottom")+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

geom_smooth(aes(x=Year, y=value,group=X,col=X),method="lm",se=FALSE,linewidth=1.5,linetype="dashed")## `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'In 1990, 11% of men and 20% of women experienced unbearable or more than average stress. Six years later, these rates rose to 27% in men and 29% in women. During this transition period, stress was statistically significantly more common among women than among men. Additionally, this period marks the fastest increase and the largest relative change in the prevalence of stress among both men and women. After 2002, the prevalence of stress in men and women has more or less converged. Stress levels fell for both men and women until 2006 and started rising again from 2008 onwards. The economic crisis that broke out in 2008 is one possible explanation. That conclusion is reinforced by the statistically significant increase in the prevalence of stress from 2008 to 2010. While the prevalence rate of stress in men has decreased slightly since 2016, in women, a change was brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, which reached Estonia in the spring of 2020 (at the time of data collection for the study). The pandemic might help explain why the prevalence of stress, which had remained at comparable levels among men and women after 2002, is now statistically significantly different again: in the spring of 2020, 17% of men and 24% of women experienced heightened stress levels.

Across age groups, the long-term trend and dynamic of the prevalence of stress is quite similar to the general trend. The rapid increase in the prevalence of stress among people aged 16–29 compared to other age groups is a notable exception. In 2018, for example, 28% of people aged 16–29 felt stressed, while the same was true for only 15% of those aged 50–64. Although age differences have decreased in the 2020 data, higher levels of stress are still most common among 16-to-29-year-olds.

Because very different situations and circumstances can act as stressors, there is no way to list all the possible sources of stress for Estonians. That is why we have chosen to focus on the stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic offers a unique opportunity to observe how a single event experienced by the vast majority of Estonians affected their stress levels. We will use this opportunity to answer two questions: how much stress did the COVID-19 crisis cause in Estonians, and which aspects of the crisis most contributed to this stress? To answer these questions, we will use data from the Estonian Biobank Mental Health Online Survey, the Estonian National Mental Health Study and the COVID-19 rapid survey.

The first of the three studies offers an initial glimpse into the stress caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The prevalence of stress was measured with the question ‘Considering everything that is going on in your life, how stressed have you been lately?’ Figure 1.2.2 shows the share of people who experienced high and very high levels of stress by gender and age group. The results demonstrated that, on average, women experienced more stress than men (38% of women and 30% of men had experienced high or very high levels of stress). In addition, the experience of stress was highly dependent on age. Respondents with a high stress level were most common in the youngest age group (50% of women, 43% of men). The share of people with high levels of stress decreased in each subsequent age group, reaching the lowest level in people aged 75 and older (17% of women and 10% of men).

J1.2.2.R

maiko.koort

2023-06-20

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)##

## Attaching package: 'dplyr'## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## filter, lag## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## intersect, setdiff, setequal, unionlibrary(tidyr)

library(scales)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete struktuur

J122=read.csv("PT1-T1.2-J1.2.2.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J122)[2:6]=c("18-29","30-44","45-59","60-74","75+")

J122_cl=rbind(J122[4:5,],J122[11:12,])

J122_cl=J122_cl[,1:6]

J122_cl$gender=c("Mehed","Mehed","Naised","Naised")

J122_cl=pivot_longer(J122_cl,col=c("18-29","30-44","45-59","60-74","75+"),"Vanus")

J122_cl=pivot_wider(J122_cl,names_from=X,values_from=value)

names(J122_cl)[3:4]=c("upper","lower")

J122_cl$upper=as.numeric(J122_cl$upper)

J122_cl$lower=as.numeric(J122_cl$lower)

J122=J122[,1:6]

J122=rbind(J122[3,],J122[10,])

J122$gender=c("Men","Women")

J122=pivot_longer(J122,col=c("18-29","30-44","45-59","60-74","75+"),"Age")

J122$gender=as.factor(J122$gender)

J122$Vanus=as.factor(J122$Age)

J122$value=as.numeric(J122$value)

#joonis

ggplot(J122)+

geom_col(aes(x=Age,y=value,fill=gender),position = position_dodge(0.9),width=0.7)+

theme_minimal()+

geom_errorbar(data=J122_cl,aes(x=Vanus,ymin=lower,ymax=upper,col=gender),pos=position_dodge(0.9),width=0.3,show.legend = FALSE)+

ylab("% of respondents experiencing high or very high stress level")+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#FF3600"))+

scale_color_manual(values=c("#FF3600","#1E272E"))+

theme(legend.title=element_blank())+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))Data from the COVID-19 rapid survey (Kender et al. 2021). The online survey asked the same people how stressed or anxious they felt on three separate occasions: in April 2020, in June–July 2020 and again in April 2021. Based on the answers, the respondents were placed into two groups: (1) those who did not feel stressed or anxious at all or no more than before and (2) those who felt either somewhat or significantly more stressed or anxious than before. As in other studies, women and younger age groups were more likely to feel more stressed or anxious in all survey waves (Figure 1.2.3). Nearly half of the respondents reported experiencing increased stress or anxiety during the surveys conducted in both the spring of 2020 and the spring of 2021. These coincided with the time that the first and second waves of the pandemic reached their crest in Estonia, with infection rates peaking and the most severe restrictions put in place to prevent the spread of the virus. In the summer of 2020, when infection rates were low and there were relatively few restrictions, only one in four respondents reported experiencing greater stress or anxiety than before. However, seasonal effects cannot be ruled out here: in addition to the temporary easing of the pandemic, the holiday period and nice weather might have also had a role in reducing stress levels during summer. Unfortunately, there is no data to verify this.

J1.2.3.R

maiko.koort

2023-06-20

library(tidyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)##

## Attaching package: 'dplyr'## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## filter, lag## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## intersect, setdiff, setequal, union#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J123=read.csv("PT1-T1.2-J1.2.3.csv",header=FALSE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J123=J123[1:17,]

names(J123)=paste(J123[1,],J123[2,])

J123=J123[3:17,]

J123=pivot_longer(J123,cols=2:11)

J123=separate(J123,1,into=c("Time","Time2","V13","V14")," ")## Warning: Expected 4 pieces. Missing pieces filled with `NA` in 90 rows [1, 2, 3,

## 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, ...].J123$Time=paste(J123$Time,J123$Time2)

J123$V13=paste(J123$V13,J123$V14)

J123=as.data.frame(cbind(J123$Time,J123$V13,J123$name,J123$value))

J123=pivot_wider(J123,names_from=V2,values_from = V4)

J123=separate(J123,2,into=c("Gender","Age")," ")

names(J123)[1]="Time"

names(J123)[4]="Mean"

J123$Mean=as.numeric(J123$Mean)

J123$`CI upper`=as.numeric(J123$`CI upper`)

J123$`CI lower`=as.numeric(J123$`CI lower`)

#joonis

ggplot(J123)+

geom_col(aes(x=Age,y=Mean,fill=interaction(Time,Gender,sep=":")),position=position_dodge(width=0.7),width=0.6)+

facet_grid(~Gender)+

geom_errorbar(aes(x=Age,ymin=`CI lower`,ymax=`CI upper`,group=Time),position=position_dodge(width=0.7),width=0.3)+

theme_minimal()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#6666CC","#4DB3D9","#982F1A","#EC1D23","#FF3600"),labels=rep(unique(J123$Time),2))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"),legend.title = element_blank(),legend.position = "bottom")+

guides(fill = guide_legend(nrow = 1))+

theme(strip.text.x = element_text(color = "#668080"))+ #Facet_grid pealkirjade vC$rv (Men and Women)

ylab("")A third perspective on the level of stress caused by the coronavirus pandemic is provided by the Estonian National Mental Health Study data, which was collected over three waves: in January–February 2021, May–June 2021 and January–February 2022. The first survey wave in 2021 asked respondents to retrospectively rate the stress caused by the state of emergency in the spring of 2020, and also to rate the COVID-related stress they were experiencing at the time of taking the survey. The second and third waves only studied the respondents’ self-reported COVID-related stress levels at the time of the survey.

From the results presented in Figure 1.2.4, we can see that the state of emergency in the spring of 2020 caused more stress in younger age groups and the least stress in the age group of 75 and over. It should be noted that retrospective evaluations may be affected by recall bias. In older age groups, people’s accumulated life experience and their individual interpretations of events may have somewhat mitigated the perception of past stress. This is indicated by the fact that current stress levels are significantly more uniform across age groups than the retrospective experience of stress.

Young people’s higher stress levels were also reflected by the results of the second survey wave, which took place in the spring of 2021, around the time that COVID restrictions were lifted. During the first wave of the Estonian National Mental Health Study, strict restrictions had not yet been re-imposed, despite the high infection rate. Figure 1.2.4 shows that during this period, COVID-related stress levels were relatively similar across age groups. A striking trend, however, was the accumulation of stress in the younger age groups: their stress level was higher in the third wave than it had been in the first.

J1.2.4.R

maiko.koort

2023-06-20

library(tidyr)

library(ggplot2)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J124=read.csv("PT1-T1.2-J1.2.4.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J124$Vanus=as.factor(J124$Age)

J124$src=as.factor(J124$src)

J124[,2:5]=J124[,2:5]*100

#näidise järgi joonis:

ggplot(J124)+

geom_point(aes(x=Vanus,y=pct,col=src),pos=position_dodge(0.3),cex=3)+

geom_line(aes(x=Vanus,y=pct,group=src,col=src),pos=position_dodge(0.3),linewidth=1.5)+

geom_errorbar(aes(x=Vanus,ymin=pct-se.pct,ymax=pct+se.pct,col=src),pos=position_dodge(0.3),linewidth=1,width=0.2)+

theme_minimal()+

labs(col="")+

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(from=0,to=25,by=5),limits = c(0,25))+

xlab("")+

ylab("")+

scale_color_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#f09d00","#FF3600","#668080"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))Even though there were differences between the three reviewed studies in terms of the questions used to assess stress and the epidemiological situation at the time of data collection, there were similarities in the results that allow us to conclude the following: (1) the COVID-19 pandemic was a significant source of stress that heightened Estonians’ stress levels; (2) the stress caused by the pandemic was perceived more acutely by women and younger age groups; (3) the dynamics of the stress level followed the epidemiological situation and the strictness of the restrictions in force.

We saw that the coronavirus pandemic caused stress for many people in Estonia. However, in order to find out exactly which aspects of the crisis were the main sources of stress, we need more detailed data. In what follows, we will look at which factors best predicted COVID-related stress with the help of data from the second wave of the Estonian National Mental Health Study (May–June 2021). In the study, people were asked to rate the extent to which various coronavirus-prevention measures and related factors caused them stress. There were a total of 27 factors, which, for the sake of clarity, have been grouped into the following sources of stress: entertainment and communication restrictions, the risk of contracting COVID-19 and its consequences, distance learning and work, restricted access to services (including medical care) and restrictions on visits, uncertainty and the ambiguity of restrictions and instructions, the requirement to self-isolate, and public rules for restricting behaviour (mask obligation, etc.).

Figure 1.2.5 shows the share of respondents who rated the corresponding source as a cause of significant stress. Somewhat surprisingly, the strongest stressor in all age groups was the risk of contracting COVID-19 and its potential consequences. For the younger age group, restrictions on entertainment and communication and uncertainty related to the pandemic were other sources of significant stress. Distance learning and work caused the most stress for people aged 35–44, who most frequently include parents of school-aged children. Public rules for restricting behaviour caused the most stress for respondents aged 45–64. In older age groups (65 and older), no sources of stress other than the risk of contracting the virus played a notable role.

J.1.2.5.R

maiko.koort

2023-06-20

library(ggplot2)

library(scales)

#data

J125=read.csv("PT1-T1.2-J1.2.5.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J125$factor=as.factor(J125$factor)

J125$factor=factor(J125$factor,levels=levels(J125$factor)[order(c(4,7,2,3,6,1,5))])

#joonis

ggplot(J125)+

geom_col(aes(x=factor,y=values,fill=Age),position = position_dodge(0.8),width=0.7)+

theme_minimal()+

xlab("Stressi allikad")+

ylab("Tekitab olulist stressi (% vastanutest)")+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#6666cc","#668080","#f09d00","#bf6900","#FF3600","#982F1A"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(legend.title=element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("Sources of significant stress (% of respondents)")+

scale_x_discrete(labels = wrap_format(10))Stress is not an inevitability that one simply has to live with. There are a number of behaviours that people use to cope with stress. James Gross has described these behaviours in his model of emotion regulation (Gross et al. 2019). This model distinguishes between various ways of coping with stress based on the stress modification mechanisms that are activated.

The model views stress and other emotional states as a cyclical process that involves:

- situation;

- attentional deployment;

- appraisal of the situation;

- physical or emotional response.

For example, stress can be caused by a difficult task at work (situation), which troubles the person even outside of work (attentional deployment) and seems hopeless (appraisal). The combination of this situation, attention deployment and appraisal causes a physical stress response to occur, which is partly reflected in an unpleasant sense of tension or anxiety. These four stages can act as a cycle of stress amplification. For example, the person experiencing unpleasant physical tension may think that they are even less likely to cope with the task in the state they are in. An appraisal of hopelessness aggravated in this way can further amplify the stress response. The vicious circle of stress can be broken in any of the four stages: by changing the situation, shifting one’s attention, changing one’s appraisal or altering one’s response.

These four strategies are the stress modification mechanisms that people use, individually or combined, in order to cope with stress. For example, people suffering from work stress can change their situation, by seeking help, asking for an extension on their deadline, or solving the problem causing them stress in some other way. When opportunities to change the situation are scarce, people can often still shift their attention, change their appraisal or alter their response.

To shift their attention, for example, people can seek entertainment that will take their mind off the source of stress. While shifting attention often provides quick relief from stress, the effect usually ends as soon as the activity selected as entertainment is concluded. Changing the appraisal of the situation can have longer stress-relieving effects. Often, there are many ways to appraise a situation. An aspect of appraisal that is particularly important in the context of stress is the perceived manageability of impending threats. The work task may be difficult, but if the person feels that they have the necessary resources, they are likely to consider the task a surmountable challenge. The ability to change one’s appraisals is often related to the ability to recover from stressful situations (resilience) (Kalisch et al. 2015). The last mechanism for coping with stress is to alter the physical or emotional response to a stressful situation. This includes, for example, going for a run in the forest or doing breathing exercises, as well as suppressing one’s emotions or airing them out in the gym or on the dance floor.

Data from the Estonian National Mental Health Study clearly show that such emotion regulation techniques are helpful in both alleviating stress and limiting the unhealthy effects of long-term stress. More specifically, the study included three statements from the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. (DERS), Gratz and Roemer 2004, in Estonian Vachtel 2011), which assessed how frequently people find it difficult to control their behaviour when feeling upset, how often they can focus on things other than their mood in moments of distress and how much power they believe they have to improve their situation when experiencing negative emotions. Based on their answers, respondents were placed into three groups: 1) those who tend to have difficulties with emotion regulation (their answers to all three questions were “sometimes” or more often); 2) those who tend not to have difficulties with emotion regulation (their answers to all three questions were ‘almost never’) and 3) those who fall in between the two groups.

Now we can ask whether people’s association with one of these three groups enables us to predict how much stress the COVID-19 pandemic caused in each person. To find the answer, we looked at the strongest source of COVID stress in the summer of 2021, i.e. the risk of contracting COVID-19 and its consequences. The results provided in Figure 1.2.6 show that the level of stress caused by the possibility of contracting the virus correlated with difficulties in emotion regulation, especially among middle-aged and older people. The more a person belonging to these age groups reported difficulties with emotion regulation, the more stressed they were about the risk of contracting COVID. The association between emotion regulation and stress was weaker in younger people. This pattern may be explained by life experience: emotion regulation has a stronger effect in older people thanks to skills acquired in the course of life.

J1.2.6.R

maiko.koort

2023-06-20

library(ggplot2)

#data

J126=read.csv("PT1-T1.2-J1.2.6.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J126=na.omit(J126)

J126$DERS=as.factor(J126$DERS)

J126$DERS=factor(J126$DERS, levels = levels(J126$DERS)[order(c(1,3,2))])

#joonis

ggplot(J126)+

geom_col(aes(x=VG3,y=Stress,fill=DERS),position = position_dodge(0.8),width=0.7)+

geom_errorbar(aes(x=VG3,ymin=LO,ymax=HI,col=DERS),pos=position_dodge(0.8),width=0.3,linewidth=0.7,show.legend = FALSE)+

theme_minimal()+

scale_y_continuous(breaks=c(25,50,75,100))+

xlab("Age")+

ylab("%")+

theme(legend.title=element_blank(),legend.position = "bottom")+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#668080","#4DB3D9"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

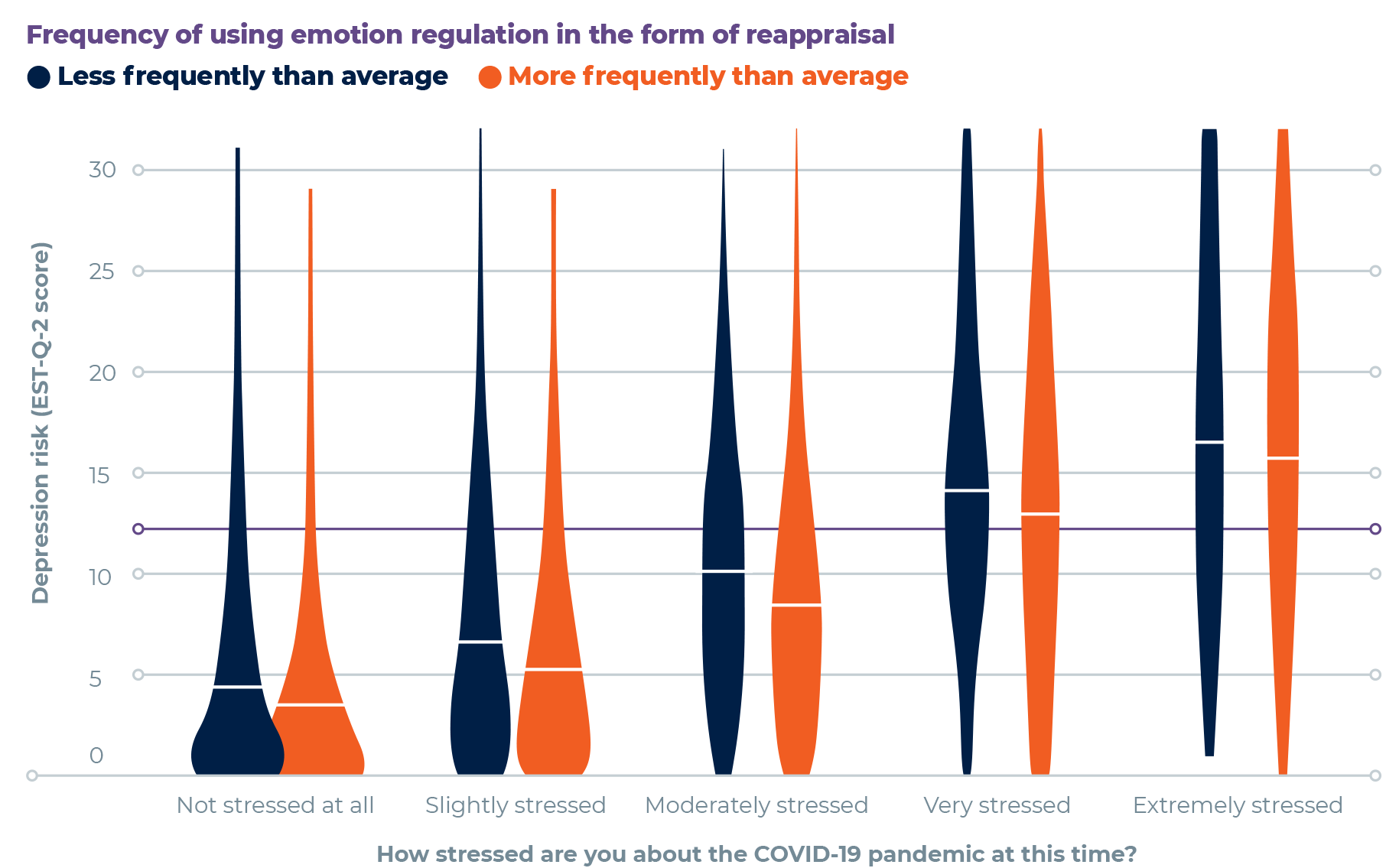

scale_color_manual(values=c("#FF3600","#1E272E","#1E272E"))In addition to reducing the intensity of stress, emotion regulation can mitigate the negative effects of long-term stress on mental health. To illustrate this pattern, we examined whether the use of emotion regulation weakened the association between the experience of stress and the occurrence of symptoms indicating depression using data from the first wave of the Estonian National Mental Health Study (January–February 2021). To measure emotion regulation, we assessed the respondents’ disposition to change their appraisal in an emotional situation, which is considered one of the most effective coping strategies. Respondents were asked to rate how often, in situations that cause negative emotions, they (a) think about what they could learn from the situation; (b) remind themselves that they are able to cope with most unpleasant situations; (c) ask themselves if the situation really means that much to them; and d) accept that unpleasant situations are an inevitable part of life. Based on the median of the average answer given to these questions, we split the respondents into two groups: those who use reappraisal strategies more than average (red shapes in Figure 1.2.7), and those who use them less than average (blue shapes). To measure stress, we used the question ‘How stressed are you about the COVID-19 pandemic at this time?’ To measure the symptoms of depression, we used the depression subscale of the Emotional State Questionnaire (EST-Q-2), where a score of 12 or higher is associated with a high risk of depression (Aluoja et al. 1999).

Fistly, Figure 1.2.7 shows that experiencing stress was strongly associated with depression. The higher the stress level, the higher the share of respondents above the depression risk threshold expressed in the figure. The share of respondents who exceeded the depression risk score was 68% of those feeling ‘extremely stressed’ about the pandemic, 36% of those feeling ‘moderately stressed’, and only 14% of those feeling ‘not stressed at all’. Based on previous studies, there is reason to believe that the relationship between depression and stress is mutual: stress affects depression, but depression also has a moderate effect on stress.

Secondly, Figure 1.2.7 shows how the use of emotion regulation moderates the effect of stress on the risk of depression: the respondents marked in red are located slightly lower in the figure than the ones marked in blue. On average, among the respondents who changed their appraisals frequently (marked in red), 4–11% less of the respondents exceeded the depression risk score than those who changed their appraisals less often (marked in blue). This pattern is consistent with the idea that changing our appraisals shields us from the negative effects of stress. The reappraisal strategy had the most impact on people who experienced moderate to high levels of stress. However, the inhibiting effect of reappraisal against depression was smaller at the margins – that is, among respondents who felt no stress or only slight stress, and those who felt extreme stress. This result was expected. If there are no strong emotions, there is no significant help in regulating them. On the other hand, very strong stress is probably caused by stressors that are adequately appraised as dangerous. In these cases, reappraising the situation is not possible or advisable. Combined, these results illustrate the role of emotion regulation as a possible shielding factor in the interplay between stress and mental health.

The average stress levels of Estonians have gone through several ups and downs over the past 30 years, resting on the personal life experiences of each individual, while also reflecting broader social trends and crises. While the stress levels of women were significantly higher than those of men in the early 1990s, gender differences between stress levels became much more uniform in the following years, until the COVID-19 pandemic that reached Estonia in the spring of 2020 raised women’s stress levels again.

While the pandemic caused increased stress for everyone, it had a greater impact on women’s self-reported stress levels. This may be due to the increased domestic burden that resulted from the lockdown and fell mainly on women, or due to women’s higher susceptibility to stress.

The prevalence of stress in younger age groups rose sharply even a few years before the COVID-19 pandemic, and young people were also under the most stress during the crisis. More than older age groups, young people suffered from the imposed restrictions, especially the decrease in entertainment and communication opportunities, as well as the uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding the crisis.

Given that the coronavirus is generally more dangerous for older people than for younger ones, it is somewhat surprising that older groups felt the least stressed during the pandemic. For them, the only significant stressor related to the crisis was the risk of contracting COVID and its consequences. he risk of contracting the virus caused less stress for those who were better at regulating their emotions.

The example of COVID-related stress demonstrates that the ability to regulate emotions and reappraise the situation can improve the ability to cope with stress and reduce the negative impact of stress on mental health and wellbeing.

WHAT MATTERS IN TIMES OF STRESS?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has put together a toolbox of simple but effective suggestions for improving wellbeing during times of stress. While these techniques are unlikely to completely eliminate stress, increasing your awareness can help significantly reduce your stress level and improve your focus.

- Grounding. First, notice how you are feeling. Shift your awareness to what is happening in your body, slow down your breathing, and when you sit, press your feet firmly into the floor. Now refocus on the world around you: pay attention to sounds, smells and colours.

- Unhooking. Negative feelings and thoughts can keep you on the hook, moving you away from the activity at hand and your values. To unhook from these feelings and thoughts, notice and name them, using labels such as ‘anger’ or ‘unpleasant memory’. (Adding the phrase ‘I notice’ to the label can help you distance yourself from the negative feeling or thought.) Now return your full attention to the activity at hand or your surroundings.

- Acting on your values. Your values describe what kind of person you want to be: how you want to treat yourself, others and the world around you. If you want to be attentive, caring, helpful and courageous, then follow these values even in difficult situations. Change the things you can change and accept the things you can’t.

- Being kind to yourself and others. Based on the values that are important to you, be friendly and gentle towards yourself and others; do not be too harsh or demanding in difficult situations. Show empathy for others and compassion for yourself.

- Making room for all thoughts and feelings. Feelings and thoughts can be very different. Accept both the good and the bad, for rejecting and denying them will not make the situation any better. Assume the position of an observer, and think of feelings and thoughts like the weather: clouds may come and go, but behind them, the sun always shines.

Aluoja, A., Shlik, J., Vasar, V., Luuk, K., & Leinsalu, M. (1999). Development and psychometric properties of the Emotional State Questionnaire, a self-report questionnaire for depression and anxiety. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 53(6), 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/080394899427692

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Gross, J. J., Uusberg, H., & Uusberg, Andero. (2019). Mental illness and well‐being: an affect regulation perspective. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.1002/WPS.20618

Kalisch, R., Müller, M. B., & Tüscher, O. (2015). A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, e92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1400082X

Kender, E., Reile, R., Innos, K., Kukk, M., Laidra, K., Nurk, E., Tamson, M. & Vorobjov, S. (2021). Teadlikkus koroonaviirusest ja seotud hoiakud Eestis: rahvastikupõhine küsitlusuuring. COVID-19 kiiruuring. https://tai.ee/et/valjaanded/teadlikkus-koroonaviirusest-ja-seotud-hoiakud-eestis-rahvastikupohine-kusitlusuuring

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Roddenberry, A., & Renk, K. (2010). Locus of control and self-efficacy: Potential mediators of stress, illness, and utilization of health services in college students. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41(4), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-010-0173-6

Selye, H. (1976). Stress without Distress. In G. Serban (Ed.), Psychopathology of Human Adaptation (pp. 137–146). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-2238-2_9

Vachtel, I. (2011). Emotsioonide regulatsiooni raskuste skaala konstrueerimine: magistritöö. https://dspace.ut.ee/handle/10062/49175

WHO (2022). Kuidas stressiga toime tulla. Illustreeritud juhend. Maailma Terviseorganisatsioon. Euroopa Regionaalbüroo. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/355276.