A MENTALLY HEALTHY POPULATION WILL CARRY ESTONIA FORWARD

- As Estonia has joined the nations with a high level of human development, the main focus in people’s daily lives has shifted from survival to improving quality of life, including the aspiration to be mentally healthy.

Human development can continue even in this uncertain age of global crises (pandemics, climate change, threat of war) if people’s mental health is supported and protected. Promoting people’s mental well-being and ability to take individual and collective action is increasingly important for society to function in crises. - People’s mental health and society’s readiness to face crises depend on people’s social and emotional sense of security and their ties to the community.

When people’s sense of belonging and security declines or disappears, it decreases their mental well-being and increases their risk of developing mental health problems. Feeling like one’s opinions and needs have not been heard causes frustration and defiance and promotes the emergence of alternative social media groups, the consumption of misinformation, polarisation, and a general mistrust of the state and other people. - Constant changes in everyday life and the cult of success put mental health to the test, requiring adaptive skills and the ability to balance demands and resources.

Maintaining mental health involves being able to adapt swiftly to constantly changing circumstances. This requires resilience. From a mental health perspective, it is important to strike a balance between demands and resources at work, in school, and in caring for family members. Large-scale disruptions to this balance can significantly reduce a person’s ability to function. - Mental health is mainly seen in terms of disorders and treatment, not contributing enough to prevention to reduce vulnerability and recognise problems early.

The lack of mental health specialists and poor availability of services is a recognised problem in Estonia. It signals that mental health is addressed when problems have reached an advanced stage and developed into diagnosable disorders. The fact that people seek help shows increased awareness and decreased stigmatisation, but it is important to strike a balance between treating disorders and preventing problems. - Many mental health determinants lie outside the field of healthcare.

Mental health over the life course is shaped by the living environment (psychosocial, digital and physical environment) and individual lifestyle choices. Maintaining mental well-being requires a comprehensive approach to prevention across various fields of life and an increased focus on the meaning of the cultural and spiritual aspects of life: shared values and traditions and the connection between natural and social ecosystems.

We live in an age of uncertainty that has brought great volatility into people’s lives. While life may not have involved less uncertainty in the past, what sets the current uncertainty apart is that it encompasses many aspects of life simultaneously and affects us all globally. The latest UN Human Development Report (HDR 2022) focuses on humanity’s preparedness to cope in our new situation, in which the threat of global pandemics, climate risks and military conflicts has sharply escalated. Meanwhile, humanity has also entered a completely new technological era, with artificial intelligence irreversibly changing decision-making processes and new energy sources upending conventional trends in the economy.

As a result of economic development aimed at unlimited growth, humanity has entered the Anthropocene, an era in which human activity has begun to threaten the future of the planet. The effects on the living environment cause unprecedented changes in the natural world and in the functioning of societies – changes from which no one can safely remove themselves. Increasing the overall uncertainty is the recognition that the usual economic and political mechanisms cannot solve the problems arising from the climate crisis. Many countries are experiencing social division and political turmoil, with changes to society that are difficult to predict. Feeding this uncertainty are the extremely rapid technological advancements of the last decade, which cause many to feel unsafe in an all-too-complex environment defined by concepts such as the green transition, the digital transition, artificial intelligence and climate neutrality. Different capacities to understand and cope with these changes exacerbate the inequalities between countries, regions and groups of people. The crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a strong catalyst in the field of mental health, both globally and in Estonia.

It has painfully highlighted the weak points in the Estonian mental health field, including the lack of mental health specialists and poor availability of services. The COVID-19 crisis has brought uncertainty, physical isolation, social distancing, loneliness, economic uncertainty and reduced physical activity – all factors known to increase the risk of mental health problems. We have yet to see the long-term mental health effects of the crisis unleashed by the war in Ukraine. Crises put people’s mental health under great pressure and undoubtedly cause stress. By forcing people to worry about the future, stress can sometimes embolden them to take action. However, excessive stress can often trigger a mental health disorder (e.g. anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder) and completely inhibit their ability to act.

„The last point that I think is necessary to address is the state of the nation’s mental health. At the moment, it is greatly impacted by the global COVID-19 crisis and the consequent restrictions in Estonia. Especially in young people, the feeling of isolation due to the restrictions causes loneliness, decreased motivation, stress and, in severe cases, anxiety, behavioural disorders and depression. This is illustrated by the significant increase in suicide attempts among adolescents in the past two years. What can we do as a society to improve the situation? The first thing we can do is talk about it. Every day that goes by without us addressing this topic is like a ticking time bomb. The other thing that every person can do is to remember to stay human. It is not difficult to be considerate, friendly, helpful and supportive of others, knowing that many people need mental support.’

In volatile times, people must be able to control their negative emotions, adjust their attitude and summon up the will to take action while acknowledging the risks. This makes it possible to cope with threats and crises, learn from them and find new ways to move forward.

As a concept, it combines stress tolerance and the ability to cope with one’s emotions, as well as flexibility and adaptability. In other words, it is the ability to balance between standing firm and bouncing back.

Growing insecurity and the fear of an uncertain future can pose a serious threat to people’s mental health and well-being, fuelling violent and angry moods in society. Ultimately, these tendencies weaken people’s will to take action and jeopardise humanity’s ability to show solidarity in managing impending threats. Uncertainty in society does not necessarily have to lead to negative future scenarios, but it does force us to make choices, propelling us to think about desirable changes that are attainable in our quest for furthering human development. From a cultural perspective, this may require rethinking our values.

Looking beyond the assumption that people are mainly or solely interested in their personal well-being and driven by rational self-interest and competitive needs, social norms and narratives that value solidarity, creativity and the spirit of cooperation allow us to view mental health and well-being from an entirely different perspective, one that promotes human development. From this angle, it is easy to see why mental health and well-being are at the centre of both the global United Nations Human Development Report and this edition of the Estonian Human Development Report. The UN Human Development Report directly links humanity’s future prospects to how well people are prepared to cope with the currently looming global threats and how this affects their mental health and well-being.

„In my opinion, a small nation like ours should support each other at every step and stop inciting hate. This way, we could improve cooperation on a national level and pave the way for a better future. I encourage the idea that every person in every community should stick together with others living around them. People need to stop glorifying the open display of intolerance. Instead of stifling life in our communities, we should all contribute to advancing it.“

By employing a systemic approach that enlists the efforts of Estonian social, health and behavioural scientists, this Human Development Report aims to shed light on the functioning of mental health and well-being through factors related to the living environment and lifestyle, in order to understand their expected impact on societal development and to visualise potential future perspectives.

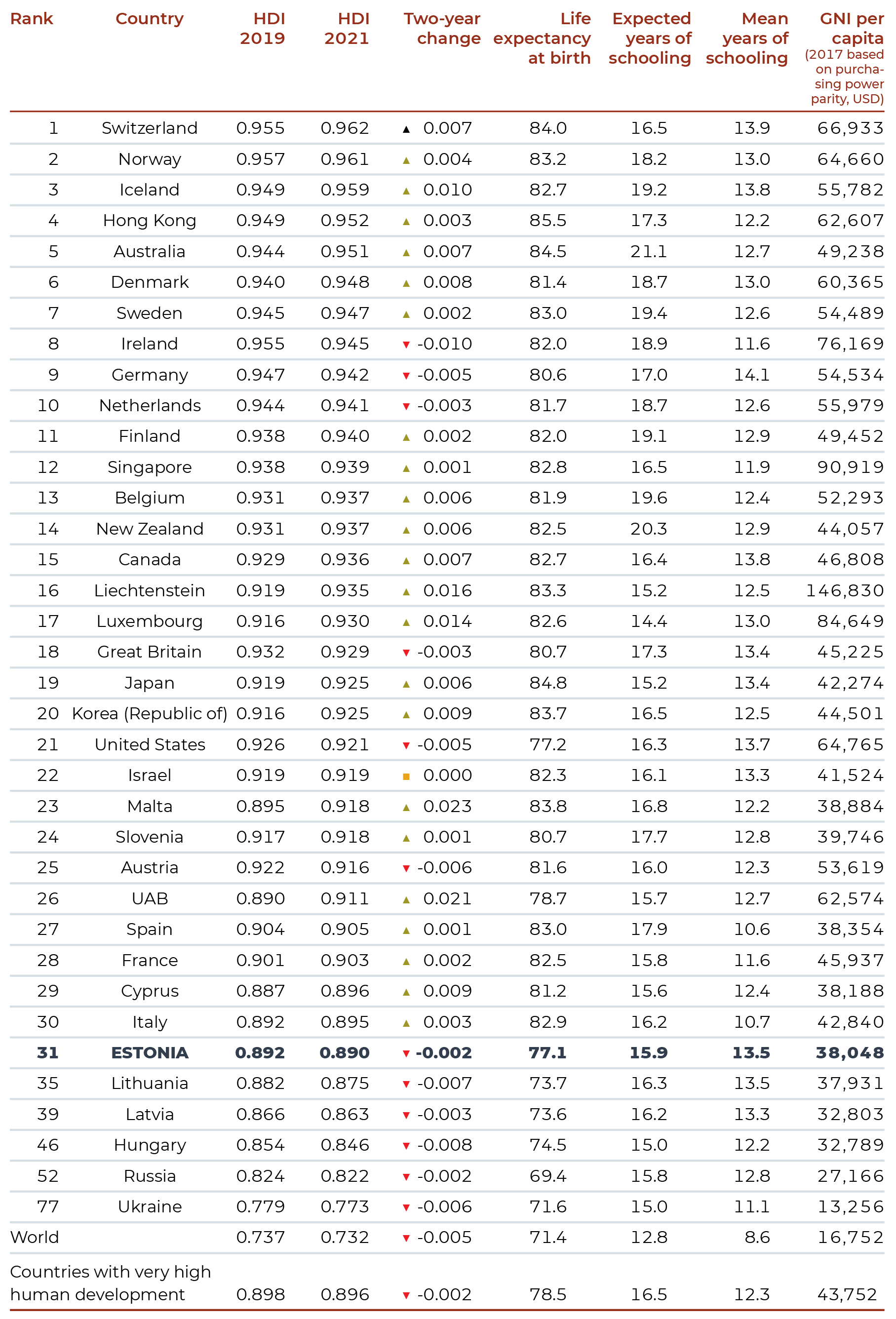

According to the UN Human Development Report 2022, the Human Development Index has been in global decline for two consecutive years for the first time since it was introduced

, with 90% of countries experiencing a slump in either 2020 or 2021 (HDR 2022).

Estonia ranks 31st in the world with an index value of 0.890 in 2021, which places it among countries with a very high level of human development, although the Estonia’s index value and place in the ranking have fallen slightly since the last report (EHDR 2020) (Table 0.1).

The main components of the Human Development Index are life expectancy at birth, education (both expected and mean years of schooling) and GNI per capita at constant prices. The life expectancy of Estonians (77.1 years) and the country’s GNI per capita (38,048 USD) are clearly below average among countries with a very high level of human development (this group includes 66 countries out of 191, with an average index value of 0.896). On the other hand, Estonia ranks relatively high in the average number of years of schooling (13.5 years). In addition, the difference between the expected and the actual mean years of schooling in Estonia is remarkably small compared to the other countries (Table 0.1).

In comparison with European countries, both the average life expectancy of Estonians and their healthy life years – another important indicator of population health – are below the European Union average. Both indicators show significant gender inequality: women have a higher average life expectancy and more healthy life years than men (Figure 0.1). On the other hand, men have a higher proportion of healthy life years (Estonian men 75%, European Union average 82%) than women (Estonian women 72%, European Union average 78%). Within Estonia, average life expectancy is marked not only by gender inequality but also by educational and regional inequality (Ministry of Social Affairs 2020a).

Mental health problems are among the top 10 causes of the global disease burden, with no improvements to this tendency in the past 30 years (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators 2022). The most recent event to negatively impact average life expectancy has been the COVID-19 pandemic. The higher mortality related to the pandemic has affected the average mortality rates of the European Union since 2020 and the average rates of Estonia since 2021.

J0.1.R

maiko.koort

2023-05-10

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J01=read.csv2("PT0-J0.1.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J01$Sugu[J01$Sugu=="(mehed)"]="Mehed"

J01$Sugu[J01$Sugu=="(naised)"]="Naised"

names(J01)[4:16]=as.character(c(2009:2021))

J01=pivot_longer(J01,4:16)

J01$value=as.numeric(J01$value)

J01$Faktor=paste(J01$Faktor,J01$Sugu,sep=".\n ")

ggplot(J01)+

geom_line(aes(x=name,y=value,col=Faktor,group=Faktor),linewidth=1)+

facet_wrap(~Riik,nrow=2)+

theme_minimal()+

scale_color_manual(values=c("#6666cc","#FF3600","#8FA300","#f09d00"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(face="bold",color="#668080"))+

xlab("")+

ylab("Vanus aastates")+

#guides(color = guide_legend(nrow=2,byrow = TRUE)) +

theme(legend.title = element_blank(),legend.position = "bottom")## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (`geom_line()`).Our understanding of mental health and well-being and their determinants has changed over time. Medical approaches equate mental health problems with psychiatric disorders. Although acknowledging psychiatry as a medical speciality in its own right was a sign of progress, providing more effective mental health care requires psychosocial interventions and the contribution of professionals outside the healthcare field. Since the adoption of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986) , there has been a growing recognition that most health determinants, as well as most health solutions, lie outside the healthcare sector, with the focus increasingly shifting towards early recognition and prevention and the promotion of health in the wider community.

Because of its comprehensive scope, the definition of health in the Constitution of the World Health Organization remains relevant today: ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO 1946). But the WHO definition has also been criticised, saying that a state of complete well-being is unattainable for most people and is far removed from people’s lived experience. Alternative definitions highlight adaptability to the environment and to changing conditions as an essential component of health(Frenk and Gómez-Dantés 2014). This makes it possible to view health as a coping resource, and one that can also be available in the presence of illness or disability.

The WHO’s definition for mental health does highlighting it as a resource but still treats it narrowly as a kind of mental state: ‘Mental health is a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.’ (WHO 2004). Other components of mental health that deserve recognition should be added to the WHO’s definition, such as internal equilibrium, the variability of emotional states, cognitive and social skills, emotion regulation, empathy, flexibility, and a harmonious relationship between body and mind (Galderisi et al. 2015).

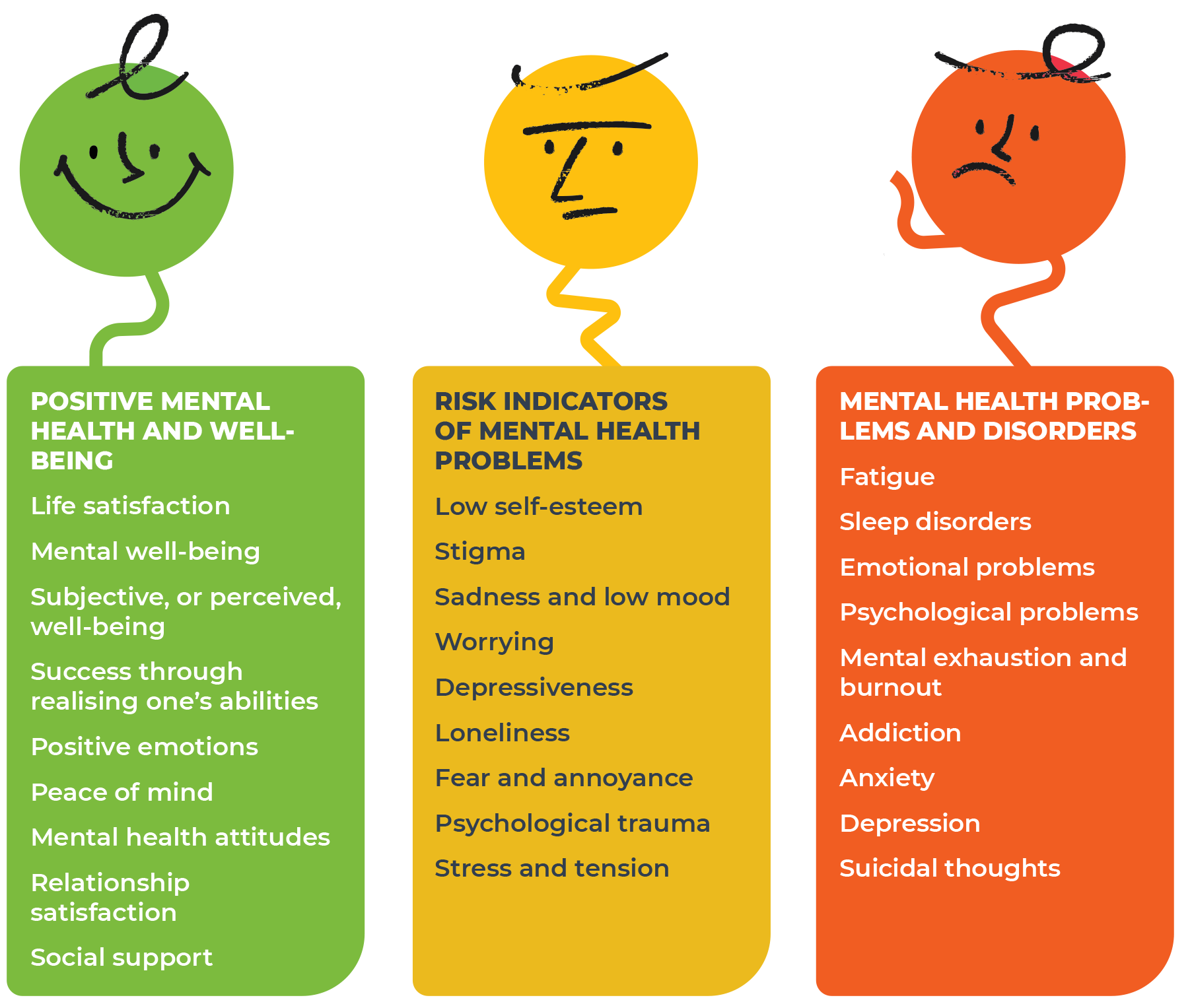

Increasing average life expectancy and growing diagnostic capabilities in healthcare lead to a rising share of sick people and risk groups in society. Focusing on assessing medical conditions means monitoring indicators of mental health disorders and risks. Strategic approaches to mental health, on the other hand, could involve more indicators relating to mental well-being and coping potential. The definitions of mental health used in this Estonian Human Development Report cover a broad spectrum that can be divided into three segments: positive mental health and well-being; risk indicators of mental health problems; and mental health problems and disorders (Figure 0.2). Combining different approaches makes it possible to explore the mental health and well-being of the Estonian population in all its various aspects, through both a normative and measurable and a subjective and interpretive perspective.

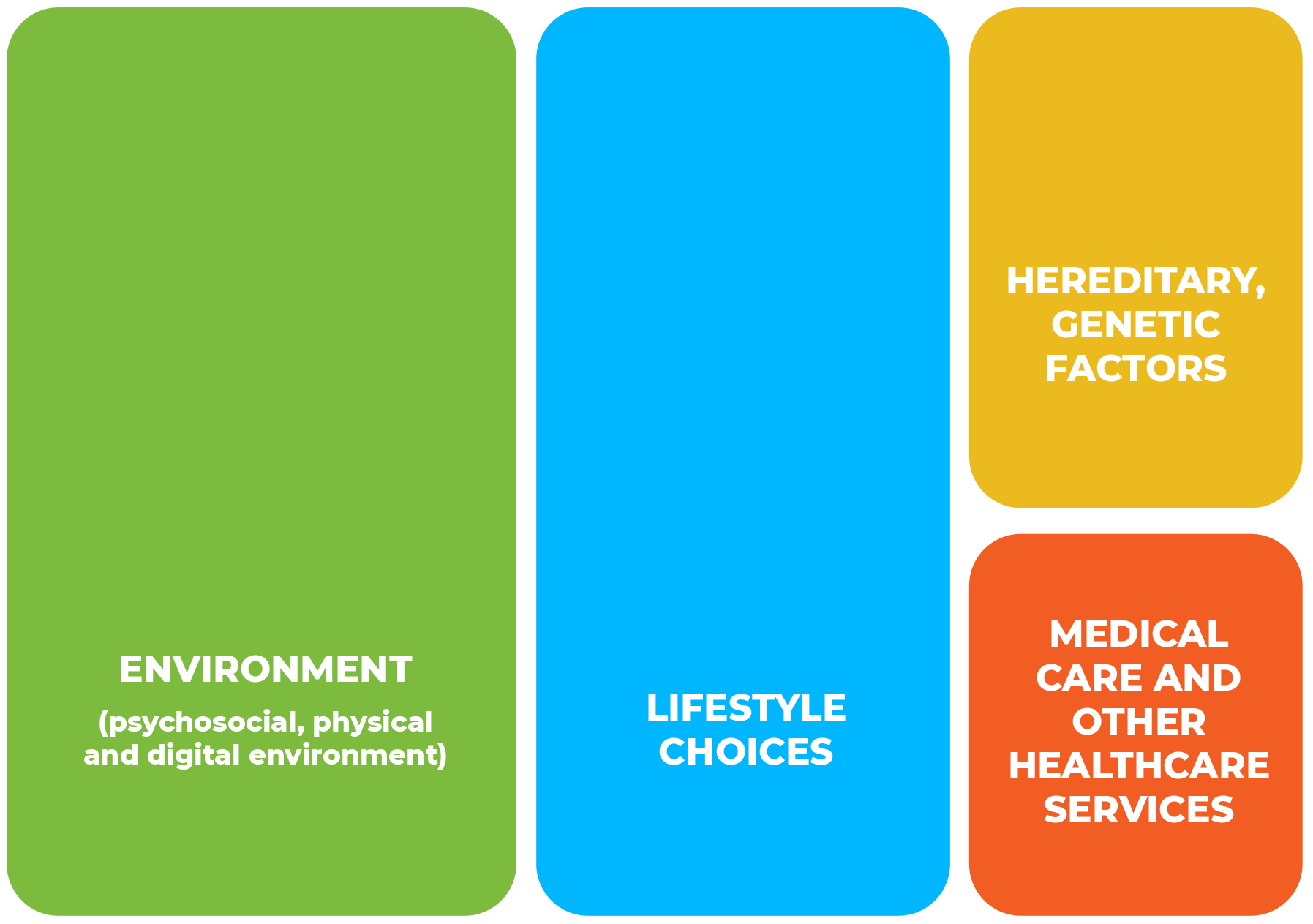

Modern approaches to health suggest that a significant part of mental health and well-being is determined by factors unrelated to the healthcare field (Detels et al. 2015; Ministry of Social Affairs 2020b; Tarlov 1999; WHO 1986, 2022). While genetic factors and health services undoubtedly play an important role in a healthy life, determinants related to the environment and lifestyle actually have significantly more impact, although the exact balance between these factors depends on the circumstances (Figure 0.2). This Estonian Human Development Report explores mental health and well-being with an emphasis on the daily living environment (psychosocial, digital and physical environment) and personal lifestyle choices (health and risk behaviour).

Any approach to mental health and well-being should pay attention to vulnerability, or the interplay of determinants preceding the onset or aggravation of problems. Vulnerability is greater at the beginning and end of the life course – in young children and older people. As humans, we are inherently vulnerable, and our wellbeing depends on cooperation.

Vulnerability is greater at the beginning and end of the life course – in young children and older people. People may be more vulnerable during some stages of the life course that present important developmental tasks (e.g. teenagers, young adults of working age). Adverse life events, crises and traumas can cause temporary increased vulnerability. And finally, vulnerability can result from social conditions, such as people’s skills and opportunities to find social inclusion (e.g. vulnerability resulting from a lack of digital competence).

As an overarching theme of the chapters of this report, we look at the challenges to mental health that arise with the increasing complexity and rising demands of life in society. In their daily lives, people face constant changes and the need to adapt, high demands and a cult of success. Both personal and social time have accelerated and been compressed (Vihalemm et al. 2017). From a mental health perspective, it is crucial to strike a balance between demands and available resources at work, in school and in caring for family members. Large-scale disruptions to this balance can significantly reduce a person’s ability to function.

„I see my parents work very hard as teachers. Their work does not end at school but often continues at home. I want people in Estonia to have more days off from work and school so that they can take time off for themselves. If people had more time for themselves, they could think about what really matters and find ways to improve life in Estonia – for themselves, their family and all of Estonia.“

The opening chapter of this report provides an overview of the mental health and well-being of Estonian people in the 21st century from the perspective of life satisfaction, success, stress, mental health problems and interventions. General life satisfaction in Estonia has grown, and several of our mental health indicators now fall within the average range in a European comparison. Yet at the same time, we are seeing an increase in mental health problems, which is particularly alarming among adolescents and young adults. These seemingly paradoxical parallel trends of increased life satisfaction and increased mental health problems can probably be explained by the general improvement in the standard of living. We have reached a level in human development where our main focus is no longer survival but the quality of life, including the aspiration to be mentally healthy. While the prevalence of mental health problems signals that society needs to act, the increasing number of reported mental health disorders, especially those diagnosed and registered in the healthcare system, also carries a positive message. It suggests reduced stigmatisation, increased mental health awareness and people’s willingness to seek help with their problems.

Following the time trends of Estonian mental health and well-being indicators, we see setbacks occur primarily in connection with transition periods and crises, most remarkably the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 and 2021, which stands out starkly due to its broad and multifaceted impact. Some of its consequences include decreased well-being in children and increased stress levels in adults. In 2018, 19% of adults reported experiencing excessive stress, but by 2020, their share had grown to 52%. And while stress is not a mental health disorder in and of itself, excessive stress serves as a breeding ground for several serious mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts.

As discussed in Chapter 2 of this report, a health-supporting lifestyle – adequate sleep, moderate physical activity, a healthy diet and abstaining from drugs – is associated with better mental well-being in all stages of the life course. The impact of these factors (both positive and negative) can multiply as they accumulate. Lifestyle choices are not just personal choices that regulate behaviour. They largely depend on opportunities, socioeconomic inequality and the surrounding living environment, including spatial planning, proximity to nature, parental role models for children and young people, and social and physical inclusion in society for older people.

In Chapter 3 of this report, we see how important it is for people of any age to have a psychosocial environment that fosters mental well-being and how vital it is to cultivate such an environment. A stable and safe home and school environment is essential for children and young people. An encouraging learning environment and a healthy lifestyle support the mental well-being of young adults. For adults of working age, a stable work environment and work-life balance are the factors with the most impact. The mental well-being of older people largely depends not only on their family relationships but also on their inclusion in the wider community. Intergenerational contact is a factor that supports mental health and well-being all the way from early childhood to old age.

In our technology-driven life, the digital environment functions as both a psychosocial and a physical environment. As we integrate digital technologies into our daily lives, we must remember that in addition to online activities, our days must also include sufficient nutrition, exercise and sleep. As a psychosocial environment, the digital world has created many new opportunities for people to experience well-being – for example, by enabling long-distance communication with loved ones. But using these opportunities requires both access and sufficient competence, which continue to be unequally distributed in society (e.g. the generational digital divide). People’s vulnerability to the risks of the digital world depends not only on their competences but also on their overall mental well-being ecosystem. The digital world today is not something separate from the ‘real world’; it calls for the same values, traits and skills, including emotion regulation and time management. You can read more about the digital environment in Chapter 4 of this report.

„As a child, I believe Estonia needs more outdoor activities. These days, almost the whole world is online, because the outside no longer offers many opportunities now that we have COVID lurking at every corner. The outdoors needs exciting activities that would invite people to join in. Towns in Estonia offer many attractions, but more remote places could also use some entertainment.“

There has been scarcely any research on the impact of the physical environment on mental health and well-being in Estonia so far. Chapter 5 of this report explores the topic from various perspectives. First, it looks at global climate change and related climate concerns, which can either decrease or increase mental well-being. Second, it approaches the topic from the perspective of annoyance caused by environmental effects (air and noise pollution). Third, it asks to what extent the spatial planning choices of an urbanised society enable social inclusion and a sense of community and facilitate direct contact with nature (green spaces and blue spaces). These choices have a significant impact on stress levels and thus on mental well-being.

The Green Paper on Mental Health (Ministry of Social Affairs 2020b) presents the optimal distribution of mental health services as a pyramid, with self-care as the foundation. We all need effective self-care techniques to cope with stress and strengthen our resilience in daily life, so emotion regulation and applying techniques

to achieve peace of mind should be a natural part of our daily hygiene. Community care and community and primary healthcare services are located in the middle layers of the pyramid, while more expensive specialist mental health services (psychiatric and psychological care) form the top. Unfortunately, the pyramid of Estonian mental health services has so far been shaped more like an hourglass: people try to cope using self-care techniques, and if that fails, they turn to a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist, without first seeking help from the community or at the primary care level. And although it is true that the number of psychiatrists and psychologists in Estonia is far from sufficient, relying on them alone would be like relying only on the rescue services to respond to fires, or only on the police to respond to traffic accidents. Preventing accidents is more effective than waiting until they happen. The same principle applies in mental health: preventing problems is cheaper than treating them, and treating them is cheaper than doing nothing.

Mental health problems impose a high social and economic cost on society. The average total cost of mental health problems in the European Union (EU) amounts to 4% of the gross domestic product (GDP), or about 600 billion euros per year. In Estonia, this figure was 2.8%, or 880 million euros, in 2021 (OECD 2021a; OECD/EU 2018). About 30% of these costs are direct healthcare costs, 30% are social protection costs, and 40% are indirect costs related to reduced employment and productivity (OECD/EU 2018).The consequent loss of work capacity is what gives mental health problems a clear economic dimension and explains why focus is shifting away from other health issues and on to mental health. Moreover, OECD calculations do not take into account all the indirect costs that may be involved, such as the increased need for social services and the treatment of concomitant physical diseases or the reduced work capacity of loved ones. Both the actual cost of mental health services and the need for them are unclear in Estonia, since the available information is fragmented, the costs are based on estimates, and many mental health disorders go undiagnosed (Foresight Centre 2020).

Estonia’s healthcare expenditure, including for mental health, is relatively low. The EU average overall share of healthcare costs in GDP is 10.9%. In Estonia, it is 7.8% (OECD/EU 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare costs increased in most countries, in Estonia even more than elsewhere (OECD 2021b). Mental health costs account for an average 6.7% of the total healthcare budget in OECD countries but significantly less, 4.0%, in Estonia (OECD 2021a).

The economic toll from mental health problems and poor mental health may be huge, and ignoring it will come at a high price. Substantial savings could be made, however, with investments in prevention and early detection (Le et al. 2021; McDaid et al. 2019; OECD 2021a). For depression and anxiety disorders, the return on investment has been calculated as five to one (WHO 2022). Given that various cost-effectiveness calculations often overlook indirect costs such as days missed from work, the real benefits of investing in mental health are likely to be even greater.

Governments only allocate a small share of their health budgets to prevention and promotion, even though most health outcomes are not linked to healthcare or treatment.

In 2020, OECD countries spent 59% (65% in Estonia) on treatment and rehabilitation, 16% (9% in Estonia) on long-term care related to health, and 19% (20% in Estonia) on medical products, mainly medicines. The remaining 7% (6% in Estonia) was spent on collective services, which include prevention and public health, including the management and administration of healthcare systems (OECD 2022). Yet, investing in extensive and effective mental health prevention could significantly reduce the need for treatment.

Globally, mental health problems account for a large percentage of disabled life years, with depression accounting for the second-largest percentage (5.6%) (WHO 2022). People’s health behaviour and awareness play an essential role in prevention and result in financial gain as well as increased subjective wellbeing.For example, if the number of disability-adjusted life years caused by depression were reduced by even 1%, the gain would amount to 29 million euros per year. It is estimated that Estonians’ health behaviour could reduce depression by 6,600 life years, which would mean a financial gain of 420 million euros per year (Foresight Centre 2020).

The idea for writing an Estonian Human Development Report on mental health and well-being was born out of concern for the mental health of the Estonian population. The authors soon realised that mental health has emerged as a broader and more substantial social issue than they had previously thought. In 2020, Estonia adopted a national mental health strategy in the form of a green paper, and a year later, a mental health department was set up at the Ministry of Social Affairs. In 2022, the government established a cross-sectoral commission for prevention. That same year, work started on the mental health action plan for 2023–2026, whose key topics included innovation, promotion, prevention and self-care, community care, mental health services, and crisis preparedness.

This Estonian Human Development Report explores mental health and wellbeing indicators from a broad perspective, with less emphasis on disorders. It focuses on factors related to the living environment (psychosocial, digital and physical environment) and lifestyle choices as the key determinants of mental health. Disorder-oriented statistics are one of the reasons why mental health has primarily been associated with the healthcare field and treatment, and why relatively few resources are spent on prevention. A great deal more of these funds could be directed to education and culture, which offer more opportunities for innovation and flexible solutions for supporting mental health. Social innovation and social entrepreneurship can provide community-inclusive solutions, creating opportunities for people to participate in meaningful relationships and activities. While potential developments in health technologies and artificial intelligence could also provide solutions, there is still too little evidence-based data on their use for prevention in the mental health field.

Our aim in writing this report was not only to highlight problems and weak points but also to show the potential for solving them. The last chapter of the report explores four future scenarios that were developed based on the main global, regional and local trends affecting the future of the mental health field and on the views articulated in co-creative expert discussions. Where the mental health field is headed depends to a large extent on future policy choices and the willingness of people and communities to help find solutions.

Arenguseire Keskus. (2020). Eesti tervishoiu tulevik—Stsenaariumid aastani 2035. Arenguseire Keskus.

Detels, R., Gulliford, M., Karim, Q. A., & Tan, C. C. (Eds.). (2015). Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health (6th edition). Oxford University Press.

EHDR 2020 – Sooväli-Sepping, H. (ed.) 2020. Estonian Human Development Report 2019/2020. Spatial Choices for an Urbanising Society. Tallinn: SA Eesti Koostöö Kogu. https://inimareng.ee/eesti-inimarengu-aruanne-20192020.html

Frenk, J., & Gómez-Dantés, O. (2014). Designing a framework for the concept of health. Journal of Public Health Policy, 35(3), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2014.26

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. 2015. Toward a new definition of mental health. – World Psychiatry, 14(2), 231–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20231.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

HDR. (2022). Human development report 2021/2022: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World. United Nations Development Programme. https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22

Le, L. K.-D., Esturas, A. C., Mihalopoulos, C., Chiotelis, O., Bucholc, J., Chatterton, M. L., & Engel, L. (2021). Cost-effectiveness evidence of mental health prevention and promotion interventions: A systematic review of economic evaluations. PLoS Medicine, 18(5), e1003606. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003606

McDaid, D., Park, A.-L., & Wahlbeck, K. (2019). The Economic Case for the Prevention of Mental Illness. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013629

OECD. (2021a). A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health. OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6-en

OECD. (2021b). Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en

OECD/EU. (2018). Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en

OECD/EU 2022. Health at a Glance 2022: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/507433b0-en.

Ministry of Social Affairs 2020a. National Health Plan 2020–2030. Sotsiaalministeerium. Sissejuhatuse link: https://www.sm.ee/rahvastiku-tervise-arengukava-2020-2030

Ministry of Social Affairs 2020b. Vaimse tervise roheline raamat. Sotsiaalministeerium. https://www.sm.ee/media/1345/download

Tarlov, A. R. (1999). Public Policy Frameworks for Improving Population Health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896(1), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08123.x

Vihalemm, P., Lauristin, M., Kalmus, V., & Vihalemm, T. (Eds.). (2017). Eesti ühiskond kiirenevas ajas. Uuringu “Mina. Maailm. Meedia” 2002-2014 tulemused. Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.

WHO. (1946). Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization.

WHO. (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Canadian Public Health Association. https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference#:~:text=The%20Ottawa%20Charter%20for%20Health%20Promotion&text=It%20built%20on%20the%20progress,on%20intersectoral%20action%20for%20health.

WHO. (2004). Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice. World Health Organization.

WHO. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338