Family relationships and family members’ self-reported mental health and wellbeing

Every person is part of a family. We are connected with our family members through family relationships, even if we do not live with them or meet them every day. The family is a child’s main context for socialisation, where they learn the meaning of coexisting with others.From family members, the child learns how to participate in a relationship and how to recognise and share their joys and sorrows. Relationship patterns acquired from the family are tacitly passed down to future generations.

Today’s families are characterised by diverse family structures – divorce and repartnering. Today’s families are characterised by diverse family structures – divorce and repartnering. At the same time, a change in family structure does not necessarily cause family relationships to deteriorate. It often leads to relationships between family members that function better (e.g. an abusive parent moving out). In any case, a change in family relationships requires adjustment and a conscious effort to function better.

International studies show that family relationships significantly affect the well-being of adults and have a decisive role in life satisfaction in Estonia and other countries where individuals have a great deal of freedom when it comes to forming couple relationships, becoming a parent or deciding on the number of children they want to have (Margolis and Myrskylä 2013). Among the various aspects of life satisfaction, positive relationships with family members are not in the best shape in Estonia. Compared with other European countries, adults in Estonia have fewer people they can rely on in times of need (Ruggeri et al. 2020). Family relationships also have a significant impact on children’s life satisfaction. If the child cannot understand why the parents are divorcing and forming a new family, and the child is not involved in decisions about their future, this can negatively impact the child’s well-being. (Kutsar and Nahkur 2021).

In this article, we seek answers to three questions: 1. How have Estonian family structures changed over time? 2. How are the mental health and well-being of children and adult family members in different family structures related to satisfaction with family relationships? 3. How do children and adults living in different family structures evaluate their mental health and well-being? We also discuss how the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic affected the mental health and well-being of children and parents in Estonia. We look at mental health and well-being primarily in terms of overall satisfaction with life. Here we define family as people who live together and are in a couple relationship or parental relationship. This includes adults in a couple relationship with or without children, single parents living with one or more of their children but whose partner does not live with the family, as well as families with children and a stepparent.

To understand the changes in Estonian family structures over the past 15 years, we used the 2005 (N = 5,642) and 2021–2022 (N = 9,088) data from the Estonian Generations and Gender Survey, which is a representative study of adult Estonian residents aged 18 to 60.

The patterns of family formation in Estonia have significantly changed over time. At the beginning of the 20th century, 70% of young people started their unions with a marriage, but among the birth cohorts of the 1960s and 1970s, more than 90% of couples started their unions within cohabitation. (Puur and Rahnu 2011). MT

The trend of childbearing not being confined to marriage only appeared in Estonia already in the 1960s, when 14% of children were born out-of-wedlock. The same trend continues today, when more than half of children are born to cohabiting parents.

J3.1.1.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-11

library(ggplot2)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J311=read.csv2("PT3-T3.1-J3.1.1.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J311$Osakaal=as.numeric(J311$Osakaal)

J311$Aasta=as.factor(J311$Aasta)

#joonis

ggplot(J311)+

facet_grid(~Sugu)+

geom_col(aes(x=Aasta,y=Osakaal,fill=Family_structure))+

theme_minimal()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#38bf7b","#6666cc","#e0e8d6","#8fa300","#81DBFE","#1E272E"))+ #Et anda ette terve vektor värve, on vaja lisada eraldi funktsioon. Siin on vaja sätida "täidet" (filli), seega scale_fill_manual

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

ylab("%")+

xlab("")The diversification of family structures can also be seen in the change in the share of single-parent and stepparent families. The majority of Estonian families consist of two parents and their biological child or children. (Steinbach et al. 2016). At the same time, the proportion of people living alone and, to some extent, people living in families with a stepparent has increased in Estonia over time. (vt figure 3.1.1). In 2021, 76.9% of all families with children (N = 3,488) in Estonia were those with two birth parents, 9.7% were single-parent families, and 13.4% were stepparent families. Compared to 2005, the share of both birth-parent and single-parent families has somewhat decreased (by 1.5% and 5.2%, respectively), while the share of people living in stepparent families has increased (6.7%), especially among women, for whom the increase is almost tenfold. (vt figure 3.1.2). Ü In the same period, the share of families with a single mother decreased by more than one-third, while the share of families with a single father more than doubled. It appears that after a previous couple relationship or marriage ends, women who raise children alone have less trouble finding a new partner than men who raise children alone.

The proportion of stepparent and single-parent families in Estonia is one of the largest in Europe. With its high proportion of stepparent families, Estonia is similar to other Eastern European countries. And its high proportion of single-parent families makes Estonia similar to Northern European countries. (Steinbach et al. 2016).

J3.1.2.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-11

library(ggplot2)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J312=read.csv2("PT3-T3.1-J3.1.2.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J312$Osakaal=as.numeric(J312$Osakaal)

J312$Aasta=as.factor(J312$Aasta)

#joonis

ggplot(J312)+

facet_grid(~Sugu)+

geom_col(aes(x=Aasta,y=Osakaal,fill=Family_structure))+

theme_minimal()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#81DBFE","#8fa300","#1E272E"))+ #Et anda ette terve vektor värve, on vaja lisada eraldi funktsioon. Siin on vaja sätida "täidet" (filli), seega scale_fill_manual

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

ylab("%")+

xlab("")In evaluating adult family members’ satisfaction with life and family relationships (18–64 years old; N = 2,466), we relied on the 2003–2016 data from the European Quality of Life Survey EQLS), which is a representative study of the Estonian adult population, using the indicators of overall life satisfaction1 and satisfaction with family life2 respectively. We also studied the quality of the relationship between children and parents3and the support provided to one another in the family4, including how these aspects of family relationships affect overall life satisfaction.The analysis indicates that family relationships play an important role in the life satisfaction of adult family members. The more satisfied one was with family relationships, the higher their evaluation of life satisfaction. This positive association is more apparent in the case of single parents but also applies to parents in a couple relationship. It appeared that across the different aspects of family relationships, only the parents’ desire to devote more time to their child was linked to life satisfaction. Again, this was more apparent in the case of single parents than parents in a couple relationship. The greater the single parent’s desire to devote time to their child, the lower their overall life satisfaction. Such results suggest that single parents realise the importance of and value their role in raising children but also feel that by themselves they cannot do everything they want to do. This perceived imbalance between their abilities and society’s expectations affects the overall life satisfaction of single parents.

When analysing children’s satisfaction with life and family relationships, we relied on the 2018 data from the International Survey of Children’s Well-Being5 (ISCWeB) for 10- and 12-year-old children, using the indicators of overall life satisfaction6 and satisfaction with family members7 respectively. For 11-, 13- and 15-year-old children, we used the 2018 data from the study of Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC), where life satisfaction was evaluated on a 10-point scale8 and satisfaction with family relationships was measured as an overall assessment of the frequency of nine joint family activities.9 In addition, we studied the quality of the relationship between child and parent,10the safety of the family environment11 and family members’ support for one another,12 including how these affect life satisfaction. Both studies have a representative sample for the respective age group in Estonia (ISCWeB 10-year-olds N = 1,013 and 12-year-olds N = 1,079; HBSC 11-year-olds N = 1,570, 13-year-olds N = 1,607 and 15-year-olds N = 1,550).

Satisfaction with family relationships affect children’s life satisfaction differently depending on age, gender and family structure. We compared children living in a family based on whether they were living with two birth parents, a stepparent, or a single parent.

Although there are some age-related differences among family structures, the general trend is that family relationships play a more critical role in life satisfaction for children living in a family with a stepparent. Also, by comparing age and gender groups, the impact of family relationships on life satisfaction differs somewhat across family structures. However, the general trend is that family relationships are tied to life satisfaction more among girls, especially as they get older.

The importance of family relationships in children’s life satisfaction is also evident when looking at various aspects of the quality of family relationships. Among 12-year-old children, the importance of these aspects is greater in the life satisfaction of children raised in a family with two birth parents or a stepparent, and somewhat less in the case of children raised by a single parent. For 12-year-old children living in a family with two birth parents, life satisfaction is mostly strongly related to satisfaction with the people they live with. For children living with a stepparent, life satisfaction is most strongly related to their assessment about home safety, and for children living with a single parent, to their perception of care in family. Among 13- and 15-year-old children, aspects of the quality of family relationships best explain the life satisfaction of girls and 15-year-old children living with a stepparent.

Girls’ greater sensitivity and vulnerability in the context of family relationships is probably supported by the persistence of traditional gender roles in child-rearing. Such findings raise questions about girls’ vulnerability in family relationships vis-à-vis their role as future mothers and the possibilities for boys as future fathers to shift towards more open relationships with their future partners and children.

Becoming a parent is usually seen as something joyful and fulfilling. Typically, a parent suffering from postpartum depression experiences anxiety, irritability, guilt, fatigue, and a lack of energy and interest. All this makes it difficult to take care of the newly born child and oneself. One of the biggest predictors of postpartum depression in fathers is postpartum depression in the mother. Lack of a support network to help new parents is also among the risk factors. Therefore, it is important to pay special attention to family relationships before and after the birth of a child – to improve strained relationships, offer help to one another, and be ready to accept and rely on others for help.Typically, a parent suffering from postpartum depression experiences anxiety, irritability, guilt, fatigue, and a lack of energy and interest. All this makes it difficult to take care of the newly born child and oneself. One of the biggest predictors of postpartum depression in fathers is postpartum depression in the mother. Lack of a support network to help new parents is also among the risk factors. Therefore, it is important to pay special attention to family relationships before and after the birth of a child – to improve strained relationships, offer help to one another, and be ready to accept and rely on others for help.

.

The existence of a couple relationship and parenting relationship plays an important role in adults’ life satisfaction. Out of all family structures, parents in a couple relationship have the highest life satisfaction, and people living alone and single parents have the lowest, especially women (vt figure 3.1.3). However, compared to other countries in the European Union, the life satisfaction of Estonian parents in a couple relationship is rather low or average, while the life satisfaction of Estonian single parents is average.

and gender.

J3.1.3.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-11

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J313=read.csv2("PT3-T3.1-J3.1.3.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J313=pivot_longer(J313, 2:3)

J313$value=as.numeric(J313$value)

J313$Perevorm=as.factor(J313$Perevorm)

J313$Perevorm=factor(J313$Perevorm,levels(J313$Perevorm)[order(c(5,2,4,1,3))])

J313$value=round(J313$value,digits=1)

J313$value[5]=6.5

J313$value[6]=6.1

J313$silt=as.character(J313$value)

J313$silt[7]="7.0"

#joonis

ggplot(J313)+

facet_grid(~name)+

geom_col(aes(x=Perevorm,y=value,fill=name))+

geom_label(aes(x=Perevorm, y=value, label=silt))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(legend.position = "none")+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#4db3d9","#38bf7b"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(color="#668080"))+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,10))+

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45))+

ylab("Average life satisfaction (on a scale of 1–10)")+

xlab("")Having a couple relationship and/or being parents also plays a role in adults’ satisfaction with family life..

People in a couple relationship, either with or without children, are significantly more satisfied with family life than single parents or people living alone, especially men (vt figure 3.1.4), moreover, it is significantly more likely that a person in a couple relationship can get help from a family member or relative in case of mild depression and a need to talk

Regardless of the presence of children, Estonian adults aged 25–34 in a couple relationship are significantly more satisfied with life than adults living alone. This suggests that creating and maintaining a relationship in young adulthood supports life satisfaction. At the same among 35-to-49-year-olds, parents in a couple relationship are significantly more satisfied with life than people in any other family structure. This indicates the importance of having children in mid-life.

A comparison of men’s and women’s life satisfaction shows that parenthood increases life satisfaction for men in a couple relationship more than for women in a couple relationship. At the same time, women who are in a couple relationship and have children are significantly more satisfied with life than single mothers. Moreover, women’s life satisfaction is higher if they are in a relationship without children than if they are living alone without children.

Satisfaction with family life decreases with age, while women’s satisfaction with family life is generally somewhat higher than men’s. There is an exception among women aged 35–49: they are significantly less satisfied with family life compared to men of the same age. Moreover, in case of mild depression and a need to talk, they estimated the likelihood of receiving help from a family member or relative to be significantly lower than men did.

On the one hand, this finding may indicate a discrepancy between women’s expectations and the reality regarding equal parenting. On the other hand, it may indicate a discrepancy between women’s self-esteem and society’s expectations about them handling motherhood. Women’s perceived lack of support from family is concerning. It indicates that Estonian adult family members may not get support from their family during the most difficult periods of their lives.

and gender

J3.1.4.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-11

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J314=read.csv2("PT3-T3.1-J3.1.4.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J314=pivot_longer(J314, 2:3)

J314$value=as.numeric(J314$value)

J314$Perevorm=as.factor(J314$Perevorm)

J314$Perevorm=factor(J314$Perevorm,levels(J314$Perevorm)[order(c(5,2,4,1,3))])

J314$value=round(J314$value,digits=1)

#joonis

ggplot(J314)+

facet_grid(~name)+

geom_col(aes(x=Perevorm,y=value,fill=name))+

geom_label(aes(x=Perevorm, y=value, label=value))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(legend.position = "none")+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#4db3d9","#38bf7b"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(color="#668080"))+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,10))+

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45))+

ylab("Average satisfaction with family life (on a scale of 1–10)")+

xlab("")Living with or separately from parents plays a role in teenagers’ satisfaction with life and family relationships

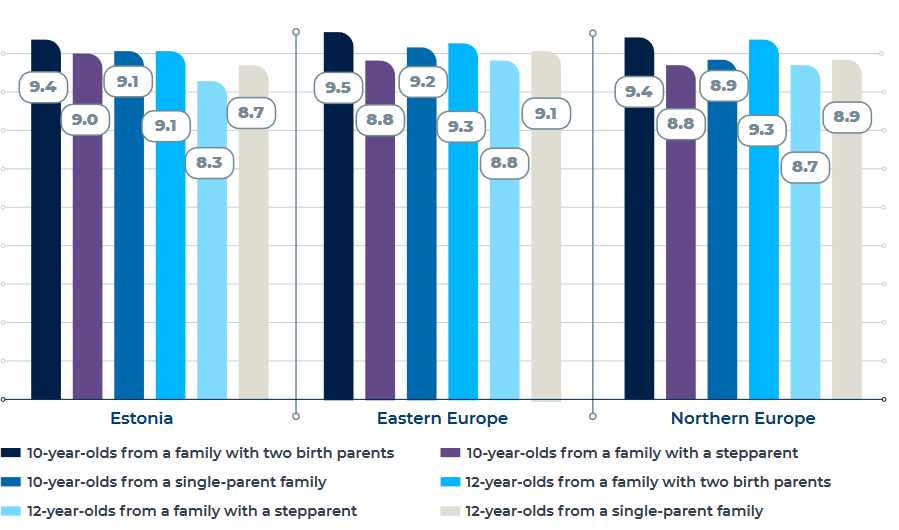

Family structure also has an impact on children’s satisfaction with life and family relationships; it becomes especially important when the child reaches adolescence. his trend is more pronounced in Estonia than in other countries in Eastern and Northern Europe (see Figures 3.1.5 and 3.1.6) (vt joonised 3.1.5 and 3.1.6). Among 10-year-olds, family structure is not significantly related to life satisfaction. However,reaching adolescence, children living with two biological parents are more satisfied with their lives and family relationships than children living with a stepparent or a single parent.

Compared to children living with both of their birth parents, 12-year-old children living with a single parent or a stepparent were significantly less satisfied with the people they live with. Also, they significantly less agree that parents listen and take their opinions into account or provide support in case of a problem. Twelve-year-old children living in a family with a stepparent perceive their family members as caring significantly less often than children living in a family with two birth parents or a single parent, and they consider their home less safe than children living with birth parents.Both 13- and 15-year-old children living with stepparents take part in joint activities with their family significantly less than children living with two birth parents. However, children living with two birth parents have a more supportive atmosphere at home than do children living in other family structures. These findings clearly indicate the need to create and maintain a supportive environment and support network for children, even when the family structure changes. Possibility of expressing their joys and sorrows and spending time with family is especially critical when children reach adolescence.

J3.1.5.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-11

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J315=read.csv2("PT3-T3.1-J3.1.5.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J315)[4]="X10.aastased.üksikvanemaga.perest"

names(J315)[7]="X12.aastased.üksikvanemaga.perest"

J315=pivot_longer(J315, 2:7)

J315$name=sub("X", "",J315$name)

J315$name=sub("10.", "10-",J315$name)

J315$name=sub("12.", "12-",J315$name)

J315$name=sub("\\.", " ",J315$name)

J315$name=sub("\\.", " ",J315$name)

J315$name=sub("\\.", " ",J315$name)

J315$value=as.numeric(J315$value)

J315$name=as.factor(J315$name)

J315$Riik=as.factor(J315$Riik)

#joonis

ggplot(J315)+

facet_grid(~Riik)+

geom_col(aes(x=name,y=value,fill=name))+

geom_label(aes(x=name, y=value, label=value))+

theme_minimal()+

theme(legend.position = "bottom")+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#1E272E","#6666cc","#0069AD","#4db3d9","#81DBFE","#e0e8d6"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

theme(strip.text.x=element_text(color="#668080"))+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,10))+

theme(axis.text.x = element_blank(),legend.title = element_blank())+

guides(fill = guide_legend(nrow=3,byrow = TRUE))+

ylab("")+

xlab("")As age increases, satisfaction with life and family relationships decreases the most among girls living in a family with a stepparent or a single parent. Almost 73% of 10-year-old girls living with a stepparent and 72% of girls living with a single parent gave their life satisfaction maximum points (10 on a 0–10 scale). However, among 12-year-olds, only 29% and 39%, respectively, gave their life satisfaction the highest assessment. The study of Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC 2018) also confirms that family structure plays a more important role in girls’ life satisfaction. As age increases, the assessments related to family relationships decrease the most among girls living in a family with a stepparent.

for 10- and 12-year-old children by family structure in Estonia, Eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland, Romania) and Northern Europe (Finland, Norway)

Recent in-depth studies show that losing their home and friends and adjusting to a new place of residence – including having to find new friends, losing and gaining family members, navigating new relationship patterns and dealing with changes in family traditions – are some of the challenges that children face after their parents separate (Ilves 2021).

Diversifying family structures create the need to support parents in adjusting with the role of a single parent or stepparent and in creating family networks that support the relationships and wellbeing of children and parents. One option is what is known as bird’s nest parenting, which allows children to continue living in their home and maintain contact with both parents, who take turns living with them in their former home (Lehtme and Toros 2019).

It was a difficult moment when I had to leave my home, it was a very difficult moment for me… I cried every day. I still had to get my things. I can’t be there every day anymore, so, yeah… moving out was very difficult for me.

This is how Kira (not her real name), a girl interviewed by Eliise Ilves in 2021 as a part of her master’s thesis, describes her experience of living between two homes (Ilves 2021).

Adults experienced more stress, and children’s satisfaction with life and family relationships decreased, during the coronavirus pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic induced more stress among Estonian adults. In October 2020, according to the Government Office’s study on COVID-19 25% of those surveyed had been under great or very great stress or tension; in March 2021, that percentage increased to 33% According to some analyses, the percentage of the Estonian adult population who experienced stress increased to as much as 52% (Reile et al. 2021). According toa survey conducted by Turu-uuringute AS on behalf of the Ministry of Social Affairs with people who have children in preschool, primary school or lower secondary school, 44% of parents considered the living arrangements resulting from the state of emergency following the COVID-19 outbreak to be stressful and burdensome. Families with children of preschool or primary school age and families with three or more children perceived living arrangements during the emergency as especially burdensome. According to in-depth studies, families perceived social isolation as the most difficult aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic period. It caused misunderstandings in families and led to conflicts (Kopõtin 2021). The state of emergency made it difficult for parents to coordinate remote work and children’s distance learning and to set limits for various activities (especially the use of smart devices). See also article 4 in this chapter, ‘The labour market, the working environment and mental health’, and article 4 of Chapter 4, ‘The use of digital technologies shaping mental wellbeing in the daily life of families’. Uncertainty about the future, the deterioration in some cases of the family’s economic situation, and the long, intensive time that families were forced to spend together caused frustration in both parents and children.

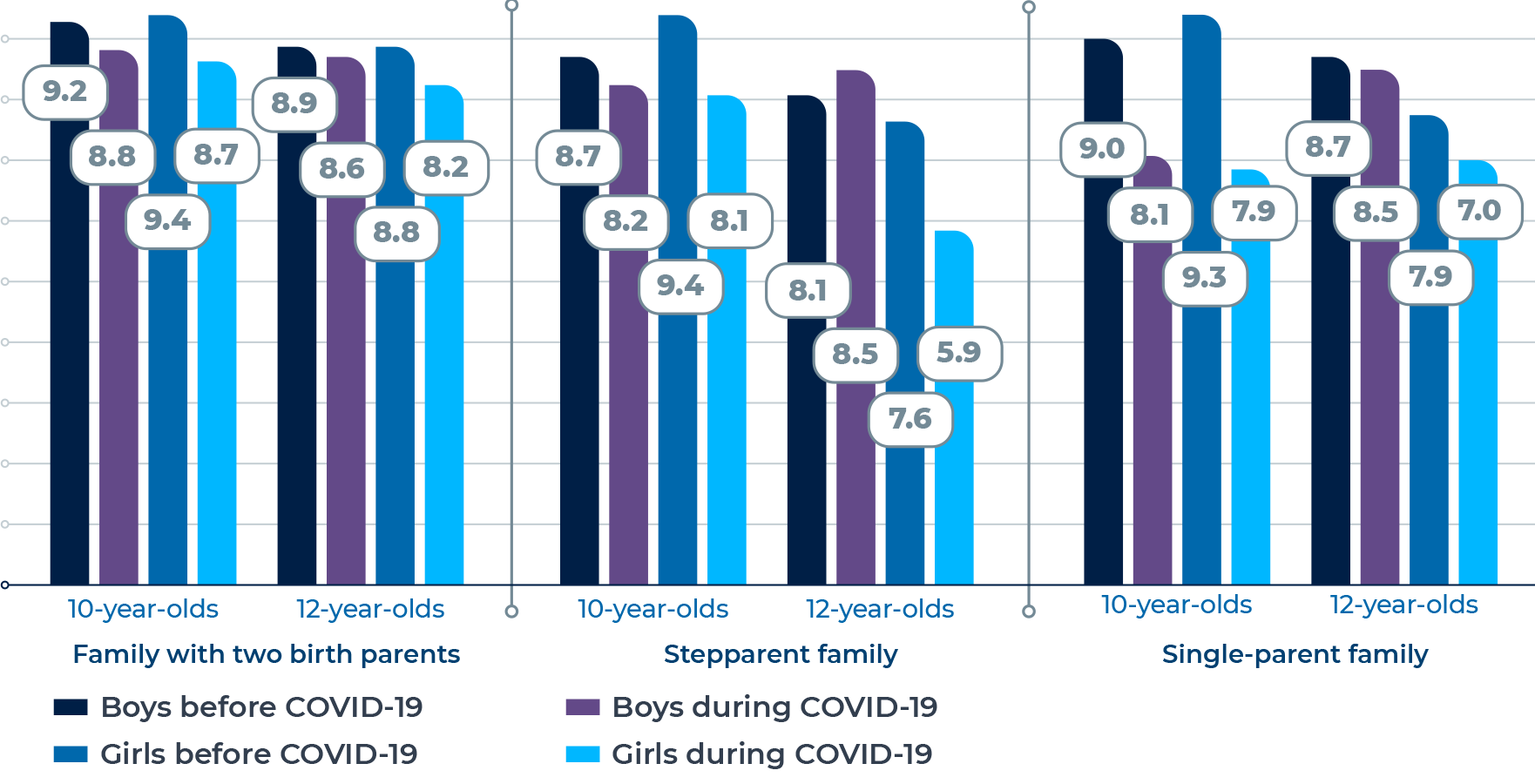

A special supplement survey on the wellbeing of fourth- to sixth-grade children (N = 1,310) conducted in the spring of 2021 revealed that children’s life satisfaction decreased during the COVID-19 period, especially among girls.(vt figure 3.1.7). Children living with a stepparent or a single parent experienced a greater decrease in life satisfaction during the pandemic than did peers of the same age and gender living with two birth parents.

boys and girls before the COVID-19 pandemic and during COVID-19, by family structure

During the pandemic, children’s satisfaction with family relationships decreased. The changes were more apparent in children living in a family with a stepparent and, to a lesser extent, in children living with a single parent.

Girls’ satisfaction with family relationships decreased noticeably. Above all, during the pandemic, girls living with a stepparent or a single parent missed their relatives (e.g. grandparents or a parent who lives or works away from home) more than boys did.How well children and young people adapted to the new situation largely depended on how close they were with their family before the emergency and how well their family coped with the effects of the pandemic (Kutsar et al. 2022). The time spent with family helped bring children and their parents closer, but it also caused tensions between family members (Kopõtin 2021). The analysis by Kutsar et al. (2022) revealed that about half of 10-13-year-old children were very strongly attached to their family, feeling great care and consideration for one another, and there was an increase in closeness within family relationships during the pandemic. About a fifth of 10-to-13-year-old children had a weak attachment to their family. During the second wave of the pandemic (spring 2021), children felt more secure and feared the pandemic less than in the first wave. At the same time, fatigue from being around family members all the time and concern about not seeing friends worsened (Kutsar and Kurvet-Käosaar 2021). Movement restrictions created challenges and were an additional source of stress for children moving between their parents based on visitation arrangements (Ilves 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic was difficult for families. The long, intensive time that families were forced to spend together during the state of emergency created new strains on family relationships. In addition to increasing stress levels, physical and psychological domestic violence occurred slightly more often during the pandemic period. In April 2020, 4% of the participants’ former or current family members had engaged in physical or psychological violence the month before. In April 2021, it was 7% of the participants. It is worth noting that among respondents aged between 15 and 24, this figure was twice as high (14%).

Summary

Estonian family structures have diversified over time. The share of adults who live alone, and the share of children who live with one birth parent or in a family with a stepparent, has increased. These kinds of living arrangements may not always be the best in terms of subjective well-being. However, the family members’ subjective well-being does not depend on family structure alone. The quality of the relationships between family members is also important. A change in a family’s structure can put family relationships under strain as their established relationship patterns no longer work. Family relationships therefore require consciously work and care, so they can be relied on in times of need. Parents are not born; people grow into parenthood. While traditional parenting requires effort, becoming a step or single parent also requires purposeful and informed action.

Many results presented in this article are not surprising. The importance of human relationships, including the importance of open family relationships and emotional closeness, is often discussed in the context of mental health and well-being. It is worrying that Estonian children and adults are not always satisfied with their family relationships and don’t have people in their families to share their joys, fears and sorrows with. Today we know that adolescence is an essential stage in the development of people’s mental health and well-being. However, this knowledge does not seem to help families to consciously prepare for periods that put family relationships under greater pressure, or to pay special attention to rethinking family relationships when children become independent.

In order to build and maintain family relationships that support the well-being of children and adult family members, conscious action is necessary at the individual, family, institutional and national level. In order for today’s children to be able to pass on the experience of a well-functioning family to their children, regardless of the family structure, it is necessary to contribute to the development of an informal and a formal support network for families. This will ensure the availability of prevention and intervention methods that support mental health and well-being for all family members and all families in Estonia.

Ilves, E. (2021). Mitme koduga lapsed: Kes, kus, mis on minu kodu? Suhtluskorra retoorika ja praktika. Magistritöö. Tartu Ülikool.

Kopõtin, K. (2021). Perede toimetulek distantsõppe, kaugtöö ja igapäevaelu ühildamisega Covid-19 tingitud eriolukorra ajal. Magistritöö. Tallinna Ülikool.

Kutsar, D. & Kurvet-Käosaar, L. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Families: Young People’s Experiences in Estonia. Front. Sociol. 6:732984. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.732984

Kutsar, D., Beilmann, M., Luhamaa, K., Nahkur, O., Soo, K., Strömpl, J., Rebane, M. 2022. Laste heaolu tulevik. Tallinn: Arenguseire keskus. https://arenguseire.ee/pikksilm/laste-heaolu-tulevik/

Kutsar, D., Kurvet-Käosaar, L. 2021. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on families: Young people’s experiences in Estonia. – Frontiers in Sociology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.732984.

Margolis, R., & Myrskylä, M. (2013). Family, money, and health: Regional differences in the determinants of life satisfaction over the life course. Advances in Life Course Research, 18(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2013.01.001

Pedersen, S. C., Terkildsen Maindal, H. & Ryom, K. (2021). “I Wanted to Be There as a Father, but I Couldn’t”: A Qualitative Study of Fathers’ Experiences of Postpartum Depression and Their Help-Seeking Behavior. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1–13. doi.org/10.1177/15579883211024375

Puur, A., & Rahnu, L. (2011). Teine demograafiline üleminek ja Eesti rahvastiku nüüdisareng. Akadeemia, 23(12), 2225−2272.

Reile, R., Kullamaa, L., Hallik, R., Innos, K., Kukk, M., Laidra, K., Nurk, E., Tamson, M., & Vorobjov, S. (2021). Perceived Stress During the First Wave of COVID-19 Outbreak: Results From Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in Estonia. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 716. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.564706

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., & Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

Steinbach, A., Kuhnt, A.-K., & Knüll, M. (2016). The prevalence of single-parent families and stepfamilies in Europe: Can the Hajnal line help us to describe regional patterns? The History of the Family, 21(4), 578–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2016.1224730