Social media use and mental health

Social media is a technology that offers its users a variety of functional opportunities to connect with others, communicate, create, share and consume textual and audiovisual content (created by others). Moreover, social media can be accessed almost anytime and anywhere, requiring only an internet connection and a suitable device (e.g. a computer or smart device). Today the internet is home to a large number of platforms and applications that can perform various general or nuanced functions but are essentially based on the ability to communicate with other people.

The main functions of social media are the free spread of information and connecting people across geographical barriers. By now, problematic aspects are also evident, such as the spread of misinformation, disinformation or malinformation and the polarisation of social groups. Although there are many threats associated with the use of social media, including cybercrime (e.g. identity theft and phishing) and cyberbullying, this article focuses on the risks associated with excessive social media use that are central to the mental health debate. These risks are often, and sometimes baselessly, described as social media addiction.

This article outlines the problematic use of social media and its associations with mental health, how it is handled in the media and among Estonian youth, and practical recommendations that could help balance (social) media use. The article is based on recent research carried out in Estonia and internationally.

The study of social media addiction is a relatively recent discipline but borrows from older research. While studying social media – a very recent technological innovation – it shares strong similarities with research on digital addiction, including smartphone and internet addiction. In fact, it can be said that the study of social media addiction stems from these other fields of research. The development of this line of research can be summarised as follows: the criteria for alcohol and drug abuse were adapted to the use of technology. This means that concepts such as withdrawal symptoms (e.g. irritability), tolerance (the idea that the same ‘dose’ of social media, smartphone or internet use is no longer sufficient) and disruptions of everyday life (problems at work or home because of excessive use of digital technologies) are now applied to technology use.

In recent years, researchers have spent considerable energy discussing whether the excessive use of digital technology can and should be considered an addiction. Many researchers studying addiction and the interactions between digital technology and the psyche have now concluded that, more often than not, excessive social media should not be described as an ‘addiction’. However, the phrase ‘social media addiction’ is still fairly widely used in the academic world. This seems to be the result of mainly two circumstances. First, many researchers want to be consistent with previous works (including the terminology). Second, the term ‘addiction’ seems to be used in cases where the researcher has yet to explore the discussions in the field. The latter happens when the researcher’s professional background is not related to (clinical) psychology or psychiatry.

It is worth noting that perceived and self-labelled ‘social media addiction’ may stem at least partially from a long-standing narrative that associates technological innovation with changes in a person’s sense of self. For example, the information collected from the diaries of students on a five-day break from social media reveals that media technologies are very important in constructing one’s personal identity and that of one’s generation (Murumaa-Mengel and Siibak 2019). The participants in this qualitative study had adopted the label ‘digital youth’ and described their generation as technologically capable and adaptable to social media. On the other hand, they also stated that ‘we are those addicts; it’s scary to even contemplate’ and tended to use generalisations about the poor mental well-being of the younger generation. However, the results of the survey conducted among Estonian youth reveals that the degree to which the survey participants thought they were addicted to social media did not correlate well with where they placed themselves on the problematic use scale.

In other words, young people may tend to think they are more dependent on social media than they actually are.

One of the biggest problems with the concept of social media addiction is that there is no way to reliably and appropriately measure it. Research in recent years has found that people’s perception of their social media use interfering in daily life is not strongly correlated with their actual behaviour (i.e. the objectively measured time and frequency of their social media use). This is one of the biggest problems in research in this field. For example, a 2018 survey among 350 social media users in Estonia found that although people’s perceived Instagram use frequency was related to poor mental health, the correlation between actual measured time spent on Instagram and depressiveness or anxiety was very weak (Rozgonjuk, Pruunsild et al. 2020). In other words, while people reported they used Instagram often (an indicator that predicted depressiveness), the actual measured time they spent on Instagram did not predict depressiveness. Therefore, perceived excessive social media use may be a better predictor of mental health problems than actual measured use.

Here a general question arises: to what extent is it even possible to define the boundaries of addiction in terms of objectively measurable behavioural data (e.g. frequency of social media use and screen time)?

As the digitisation of people’s everyday life is likely to continue, distinguishing between normal and excessive daily social media use makes answering that question difficult.

In addition to the fact that people’s perception of their social media use does not correspond to actual behaviour, the specifics of social media also raise questions. Should the use of different platforms be distinguished? In cooperation with American and German researchers, we found that social media cannot be treated in a generalised way: different social media platforms can have different potential for addiction (Rozgonjuk, Sindermann et al. 2021), vt Figure 4.3.1.

J4.3.1.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-13

library(ggplot2)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J431=read.csv("PT4-T4.3-J4.3.1.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J431$digi=reorder(J431$digi,J431$keskmine)

#joonis

ggplot(J431)+

geom_col(aes(x=digi,y=keskmine,fill=digi))+

geom_errorbar(aes(x=digi,y=keskmine,ymin=alumine_usalduspiir_95,ymax=ulemine_usalduspiir_95),width=0.2)+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#323E4E","#E9A419","#4D96B9","#2E938B","#634988"),breaks=rev(levels(J431$digi)))+

theme_minimal()+

coord_flip()+

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(0,60,5))+

theme(legend.position = "none")+

theme(legend.title = element_blank())+

xlab("")+

ylab("Average problematic use score (95% confidence interval)")We also need to consider the way social media is used. In recent years, a distinction has been drawn between socially active and passive use of social media. The former is divided into active public use (e.g. posting content and responding to others’ posts) and active private use (e.g. sending messages). Passive use means spending time on social media, such as browsing the news feed and viewing other people’s profiles.

lower well-being.

This distinction is important because socially active social media use (i.e. for communication) has generally been found to be associated with higher levels of well-being, while passive social media use is associated with lower well-being (Verduyn et al. 2020).

To sum up, although studies focusing on social media addiction continue to be published, it is a fairly complex field with many nuances beneath the surface..

While there are problems with the research of social media use (such as the use of terminology referring to addiction), the links to mental health cannot be ignored. One might think that social media use is associated with better mental health, as it effectively satisfies people’s fundamental need to communicate. Social media also makes it possible to raise social capital (build relationship networks between people) quickly and effectively, thus strengthening the feeling of social cohesion. According to a cross-sectional study conducted in 2018 among 436 Estonian social media users, this, in turn, can have a positive effect on well-being (Gugushvili et al. 2020). However, several experimental and meta-analysis studies have shown that social media use is weakly but negatively related to users’ well-being and mental health (Appel et al. 2020).

Why is excessive social media use associated with poor mental health? Researchers have suggested social comparison as one possible explanation. Social comparison is comparing one’s own abilities, characteristics and opinions with those of others to get the most accurate self-image possible. People may compare their appearance, social status and many other characteristics with those of others, but importantly, the comparison requires a comparator – someone to compare oneself against. Choosing a comparator can depend on the direction of comparison: there is a difference between an upward comparison (with people who are better than oneself in terms of the comparable characteristic) and a downward comparison (with people who are worse in that respect). Comparing oneself with those who are more successful can inspire and motivate, but it can also make one feel inferior and envy the comparator. For social comparison related to social media, the feelings of envy can be explained by the fact that people share a more positive image of themselves and their activities on social media than is actually the case in everyday life.

Research confirms that people tend to compare themselves with those who are more successful, and this can cause negative emotions (e.g. envy and resulting frustration), which in turn leads to a deterioration of well-being or mental health (Gugushvili et al. 2020). People who tend to experience sadness and anxiety and who have low self-esteem can be particularly affected when comparing themselves to others. Research also shows that the use of social media platforms can cause information overload, the postponing of important activities and a decrease in face-to-face interactions, all of which can harm people’s well-being (Gugushvili et al. 2020). , or the fear of missing out, has also been identified as an important factor in the negative relationship between the use of social media and well-being. People with high FOMO have a greater fear of missing out on other people’s (such as friends’) activities and experiences. Thus, researchers have hypothesised that FOMO is also associated with greater social media use. In the Estonian sample, it was confirmed that higher FOMO is related to poor mental health (Gugushvili et al. 2020). Although several studies have shown that FOMO is associated with perceived excessive use of smart devices and social media, recent findings of analyses that measure actual smartphone use and combine survey data suggest that FOMO may not predict actual measured smartphone use well (Rozgonjuk, Elhai et al. 2021).

social media consumption or vice versa.

However, it is important to note that researchers have not reached a consensus on the direction of the causal relationship: whether social comparison, sadness, FOMO, etc. increase social media consumption or vice versa.

The problems associated with the excessive use of social media in everyday life should not be underestimated, especially since there is reason to believe that some people are more severely affected by the excessive use of social media than others. However, it is also worth noting that the negative effects of excessive use and the prevalence of social media addiction are consistently framed as a much bigger problem than it actually is.

values. This is an example of ‘moral panic’.

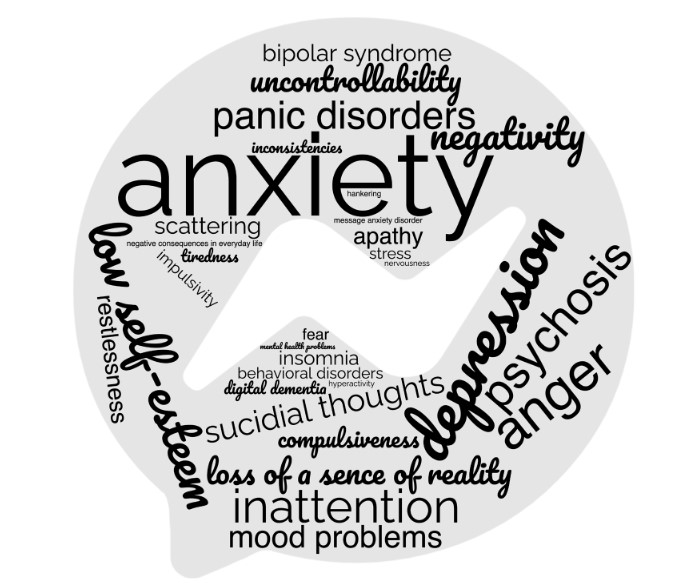

In other words, public discussion and the media tend to label the (excessive) use of social media as dangerous for (mental) health and for social interests and values. This is an example of ‘moral panic’. The increasing use of social media is one of the reasons why overtones of moral panic accompany the media narrative. Another reason may be the fact that addiction as a potential social problem attracts the media: discourse on addictions of various kinds has always been amplified in the media, and the Estonian news media portrays social media use as a problem that urgently requires a cure. For example, various problems related to mental health are discussed alongside social media addiction in almost two-thirds of the articles published in the Estonian media (Sinivee 2022). Figure 4.3.2 shows the frequency of words related to mental health in articles discussing excessive social media use published in the Estonian media between 1 January 2013 and 1 January 2021.

Although a negative tone prevails in media coverage of social media, research has shown that young people use social media primarily to communicate with each other, and as previously stated, socially active social media use is more likely to be associated with better mental health.

with better mental health.

Naturally, it is vital to notice and help young people who are trying to cope with their (excessive) use of social media and create and maintain in-person social relationships. But we need to keep in mind that, according to the results of a cross-sectional study conducted in 2018 (987 young people aged 11–19 years participated), most young people are not addicted to the use of social media (Sinivee et al. 2022), even if they describe themselves as such.

Every spring since 2016, students participating in one of the internet research courses at the University of Tartu have been asked to take a five-day break from social media. The participants record their experiences and feelings free-form in a diary, and at the end of the course, they may give the diary up for research. By the time this article was written, 120 students had shared their diaries, which provide a comprehensive insight into today’s youths’ relationships with smart devices and social media. With a few exceptions, these are 19-to-23-year-old undergraduates in social sciences and humanities. Most are Estonians, but it is estimated that a quarter of the submitted diaries belong to foreign students. There are certain cultural and contextual differences, but in general, the topics covered by Estonian and foreign students are similar. Globally, young adults have many things in common. The diaries of the social media break (Lepik and Murumaa-Mengel 2019) revealed two broad frameworks in the associations between young people’s mental health and the use of social media.

First, the break acts as a wall, isolating the subject: too little communication results in lower well-being.

Young people are used to the fact that everything – friends and family, love and work, entertainment and information – is always at their fingertips. Therefore, they often describe a social media break as a lonely time when there is no way to check whether their existing social relationships still stand and whether anyone notices that ‘I am actually not dead’. This finding is consistent with the results of studies described above – active social media use is beneficial for psychological well-being.

Second, the break acts as a vacation: it is an excuse for reduced communication and thus increases subjective well-being. The social media break is seen as an opportunity, as a way to regain control of communication and time and to return to good old ‘technostalgia’. It is usually preceded by a perceived decrease in the ability to focus and the expectation and hope that even a short break from the constant stream of information will provide mental clarity and the ability to focus again. Moreover, many students describe experiencing an avalanche of notifications, beeps, parallel conversations, videos and images, and reactions and rituals, resulting in feeling buried alive under expectations from numerous sources to communicate.

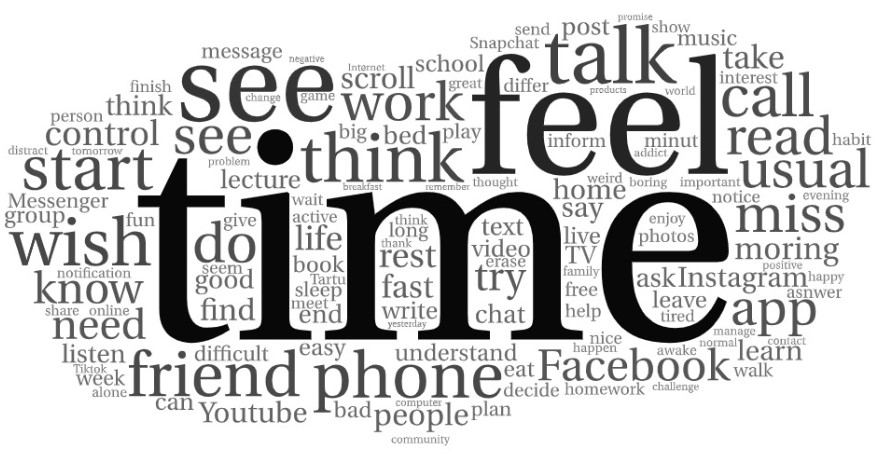

Taking an overview of the diaries (Figure 4.3.3), we see that the most frequently used word is ‘time’: the fast or slow passage of time was mentioned in almost all diaries (a total of 1,743 times). Variations of the word ‘feel’ (1,381), which is typical vocabulary for diaries, take second place, and references to the main device – the phone – are in third place (mentioned a total of 1,295 times). One notable finding is that the phone becomes almost useless if it is not a gateway to social media. The fourth most frequently mentioned word in the diaries was ‘friend(s)’ (a total of 915 times). References to specific social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, are also found in the diaries.

In addition, productivity was a dominant value in the diaries. During the social media break, many felt incomplete as the normal information-filled and fast-paced, parallel activities of everyday life were taken away. On the positive side, the young people wrote that the days passed ‘surprisingly quickly’ and were ‘relatively productive’, as slowness and idleness are something to avoid, according to many diaries.

If psychologist Abraham Maslow, who proposed the concept of the hierarchy of needs, were to read these diaries, he would definitely point out the symptoms of deprivation in the students’ descriptions. For example, they need social media to fall asleep (falling asleep to videos with soothing content), to feel safe in the urban environment (sharing their location with friends on the way home from a party), to maintain friendships (such as streaks on Snapchat maintaining a chain of daily interactions) or to share the latest piece of digital art with their followers.

If a person is concerned about their (excessive) use of social media, they should consider cutting back. Research has shown that limiting the use of social media can also reduce the use of smart devices (and vice versa). One possible approach is to dial down the functionality of the device. For example, experiments with setting the screen to grayscale have reduced smartphone usage. You may find the following tips helpful if you want to limit your use of smart devices and social media.

You may find the following tips helpful if you want to limit your use of smart devices and social media.

- Turn off unnecessary reminders and notifications (sounds, banners and vibration).

- When your phone is in silent mode, keep it face down and out of reach.

- Set a screen lock and make unlocking the screen as inconvenient as possible.

- When you go to bed, leave your phone in another room or keep it on silent mode and face down.

- Reduce screen brightness, set the screen to grayscale and activate the blue light filter (known as night mode).

- Create a separate folder for social media apps, add all relevant apps there, and move the folder away from the home screen.

- Let your loved ones and colleagues know that you will not check your messages often.

- If you do not need your phone, leave it at home.

Summary

Without a doubt, social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter have shaped the norms and practices of daily life. On the one hand, this effect can be negative (echo chambers and information bubbles, polarisation, comparing oneself with others, etc.). On the other hand, social media fulfils many valuable functions, and well-being could suffer without it.

Although social media use is often associated with mental health problems, the mass media can overemphasise this topic and it is often unwise to consider social media as the root cause of mental health problems. Generally, active communication supports well-being. Research on social media has also shown that active communication with others is linked to increased well-being. A study of social media break diaries revealed that not using social media limits communication, which, in turn, can lead to loneliness. Social relationships were one of the main themes in the diaries. Young people often wrote about how they missed their friends, loved ones and family members while on break. At the same time, however, social media encourages comparing oneself with others. And as people tend to share the better aspects of their lives on social media, self-perception can be distorted by comparing one’s life against the positive image that other people choose to project. However, a social media break can also support well-being: activities are not interrupted in order to react to social media notifications, and social comparisons that distort self-perception are reduced. Based on these assumptions, recent research has proposed (relatively uncomplicated) measures to control social media use, such as turning off pop-up notifications, reducing app appeal and functionality, and cutting down the role of social media in everyday life.

Appel, M., Marker, C., & Gnambs, T. (2020). Are Social Media Ruining Our Lives? A Review of Meta-Analytic Evidence. Review of General Psychology, 24(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019880891

Gugushvili, N., Täht, K., Rozgonjuk, D., Raudlam, M., Ruiter, R., & Verduyn, P. (2020). Two dimensions of problematic smartphone use mediate the relationship between fear of missing out and emotional well-being. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-2-3

Lepik, K., & Murumaa-Mengel, M. (2019). Students on a Social Media “Detox”: Disrupting the Everyday Practices of Social Media Use. In S. Kurbanoglu, S. Spiranec, Ü. Urdagül, J. Boustany, M. L. Huotari, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, & R. L. Cham (Eds.), Communications in Computer and Information Science Series (Vol. 989, pp. 60–69). Springer Nature Switzerland.

Murumaa-Mengel, M., & Siibak, A. (2019). Compelled to be an outsider: How students on a social media detox self-construct their generation. Comunicazioni Sociali, 2, 263−275.

Olson, J. A., Sandra, D. A., Chmoulevitch, D., Raz, A., & Veissière, S. P. L. (2022). A Nudge-Based Intervention to Reduce Problematic Smartphone Use: Randomised Controlled Trial. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00826-w

Rozgonjuk, D., Elhai, J. D., Sapci, O., & Montag, C. (2021). Discrepancies between Self-Reports and Behavior: Fear of Missing Out (FoMO), Self-Reported Problematic Smartphone Use Severity, and Objectively Measured Smartphone Use. Digital Psychology, 2(2), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.24989/dp.v2i2.2002

Rozgonjuk, D., Pruunsild, P., Jürimäe, K., Schwarz, R.-J., & Aru, J. (2020). Instagram use frequency is associated with problematic smartphone use, but not with depression and anxiety symptom severity. Mobile Media & Communication, 8(3), 400–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157920910190

Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2021). Comparing Smartphone, WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat: Which Platform Elicits the Greatest Use Disorder Symptoms? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0156

Sinivee, R. 2022. Media framing of social media addiction in Estonia [Avaldamiseks saadetud käsikiri]. European Journal of Health Communication.

Sinivee, R., Sisask, M., Tiidenberg, K. 2022. Social media addiction among Estonian youth [Avaldamiseks saadetud käsikiri]. Social Media + Society.

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., Massar, K., Täht, K., Kross, E. (2020). Social comparison on social networking sites. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.002