The use of digital technologies shaping mental well-being in the everyday life of families

In today’s society, people live in a world shaped by the media, or a mediatised lifeworld1, because both digital technologies and digital media have a significant role in the everyday life and functioning of families. Recently, several quantitative and qualitative studies have been conducted in Estonia examining the role of digital technologies in the daily life of families. In this article, we take a closer look at the findings of several studies.

The results of a survey conducted among parents of children aged 0 to 3 (N = 400) and a six-month ethnographic research of one family, both conducted as part of Elyna Nevski’s doctoral thesis (2019), provide information about the use of digital technologies in families with toddlers and preschoolers and the role of parents in guiding toddlers’ use of technology. The results of a survey conducted by the EU Kids Online research network among 9-to-17-year-old Estonian children (N = 1,020) and their parents (N = 1,011) in 2010 and 2018 demonstrate parental mediation strategies for guiding children’s use of digital technologies (Kalmus, Sukk, Soo 2022). Marit Napp and Andra Siibak’s (2021) interviews with 8-to-13-year-old children and their mothers (total N = 40) who use applications to track their child’s location provide additional insight into the practices of families using what is known as technological mediation. The experiences of the participants in two qualitative studies reveal the changes in digital media consumption practices during the coronavirus crisis. Ten Estonian families participated in the DigiGen study (on the impact of technological transformations on the Digital Generation) conducted in 2020/2021, where individual interviews were conducted with ten children aged 5–6 or 8–10 and two other family members, one of them a parent (total N = 30) (Kapella and Sisask 2021). In order to investigate changes in toddlers’ use of digital devices during the COVID-19 pandemic, mothers of 2-to-4-year-old children (N = 15) were interviewed for Pihel Sahk’s master’s thesis (2020)

Based on the results of the empirical studies, this article provides an overview of the practices, understandings and agreements on the use of digital technologies in Estonian families, as well as the changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. We also discuss the perceived associations between the use of digital technologies and the mental well-being of children, parents and families.

The studies revealed that family members recognise both beneficial and harmful effects of the use of digital technologies in the families’ everyday life and communication with loved ones. From the perspective of mental health, the importance of digital technologies was particularly clearly felt when maintaining relationships among family and friends in social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, interviews with mothers of 2-to-4-year-old children revealed that video calls were almost the only way for toddlers to stay in touch with their grandparents or their father working abroad during the state of emergency in the spring of 2020.

Today, various portable devices (e.g. smart watches) and phone applications (e.g. Find My Kids, Google Family Link and Family Tracker) enable parents to keep track of their children’s whereabouts even when they cannot accompany the child. A 2021 survey that used Q methodology2 and interviewed families who use applications for tracking revealed that parents adopt such technological aids mainly for the safety of their children. Parents stated that such apps are a quick and convenient way to assert parental control (e.g. by providing a quick look at where the children are and what they are doing) but also have a disciplinary effect on the child, since the child knows that their location can be tracked.

However, from a mental health perspective, it is important to note that tracking apps are perceived as providing peace of mind and reassurance. Therefore, many parents who participated in the study felt that the use of digital tools with real-time geolocation made it possible to ensure the child’s safety. They added that with the support of digital tools, parents can fulfil their parental duties more efficiently and, simultaneously, be a more devoted parent.

Interviews and Q sorting with preadolescents revealed that they also get confidence and peace of mind from tracking apps. Several children who participated in the study revealed that in the event of problems or unexpected situations (e.g. if the child got lost), their parents could still help them, thanks to geolocation apps. Therefore, many parents and children trusted such technological applications and did not have much to criticise, as the apps helped create a sense of control and security.

1 ‘Lifeworld’ is people’s complete and meaningful relationship with the surrounding reality, i.e. the perceived world in which they live (Vihalemm et al. 2017).

2 Q methodology (also known as ‘Q sort’) is the systematic study of participant viewpoints in the context of public perceptions. Participants are asked to sort a series of statements related to specific topics that reflect perceptions in public discourse (e.g. media and scientific literature) and rank the statements according to the extent to which they agree with them.

WHY DO FAMILIES USE GEOLOCATION APPS?

A mother: Certainly [one of the reasons is] peace of mind and the fact that I don’t have to annoy the child all the time, like ‘Hey, are you coming already? Where are you already?’ right, ‘Did you get on the bus yet?’ or well, whatever. […] Rather, mostly yeah, for a sense of security for myself and maybe also a sense of security for the children.

A son (10 years old): Well, definitely [one of the reasons is] my safety. If something were to happen, if I don’t answer calls for, I don’t know, a long time, it would be good to know where I am and know that I’m in a safe place. So this is mainly for my safety. […] And that itself makes me feel safer if my mum gets the opportunity to find out where I am. Or if by chance something happens, someone kidnaps me and I am not available, then they know where I am. I think it will be easier to find me then or something.

Even though, as a rule, the 8-to-13-year-olds who participated in the study favoured and accepted the use of tracking applications, the analysis showed that the use of such digital technological aids can also cause conflicts and misunderstandings between children and parents and undermine trust between them. Furthermore, the use of tracking apps can lead to various breaches of privacy, in terms of both interpersonal privacy (i.e. the communication between children and parents and shared information) and commercial privacy (i.e. the commercial interests of the companies providing the services) (Stoilova et al. 2019). Therefore, it is important to understand the use of tracking apps, as well as many other digital applications and platforms that enable parental monitoring (e.g. online school environments or parental control applications), in the context of children’s rights, including the right to privacy and autonomy (Conventions on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 25, 2021). (Conventions on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 25, 2021).

The research shows that the possible effects of using digital technologies depend on the specific context. The effects may sometimes be positive, sometimes neutral and occasionally negative for the same areas of life. For example, the results of a survey conducted among parents of children aged 0–3 years revealed that adults have a number of positive expectations for digital technologies. Almost half of the parents who participated in the study allowed their 0-to-3-year-old children to use digital devices. Their stated rationale was that, with the help of a smart device, their children would learn new skills (68%) and acquire new knowledge (54%) (e.g. learn new words and numbers in both their mother tongue and a foreign language). They also said they did so because it would entertain the child (55%). Here, it is important to note that 67% of the parents who participated in the survey admitted that they leave their toddler alone with digital technology while they do household chores (cook, clean, handle the other child, etc.) or – in the context of mental health – take time for themselves to rest a bit or use digital tools for other purposes at the same time.

This confirms that digital technologies have become a kind of ‘babysitter’ for families.

The need for a digital ‘babysitter’ increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation as families’ usual life arrangements were turned upside down. Interviews with mothers of 2-to-4-year-old children showed that toddlers’ habits of using digital devices changed significantly during this period. It is also important to note that toddlers’ use of screen media during the pandemic was directly influenced by the child’s family background. This included the parents’ employment status and character of work (e.g. the possibility of working from home and distributing work tasks or going on parental leave) and the presence of siblings (older siblings’ distance learning and screen media usage habits, the sleep schedule of younger siblings). It also included the family’s economic circumstances, such as their living arrangements (in a house, part of a house, or apartment), and the presence of various digital technology devices, as well as general restrictions in society (e.g. kindergartens partially closed, playgrounds and playrooms closed).

Interviews with mothers revealed that screen time increased for many toddlers during the pandemic as parents allowed them to use previously prohibited devices (e.g. smartphones and tablets). By acquiring new digital skills, children expanded their range of digital activities (e.g. they started making video calls, watching videos of gymnastics lessons made by kindergarten teachers or listening to bedtime stories read on Zoom). In addition, digital technologies provided shared entertainment for families during the state of emergency. For example, families organised movie nights, watched live concerts, and played video or computer games together. Therefore, digital technologies played a central role in ensuring the mental well-being of family members big and small during the state of emergency.

However, since children were allowed screen time mainly on weekdays, when parents were busy with work, helping older siblings with distance learning or putting younger siblings to sleep, digital technologies also became the primary means of maintaining discipline. It is important to note that the time spent in front of screens increased the most among 2-to-4-year-olds who live in apartments. Since public playgrounds were also closed during the state of emergency in spring 2020, it was not so easy for parents to send their children to play outside.

Interviews with Estonian families in the DigiGeni study revealed that both adults and children are concerned about the harmful effects of digital technologies on mental and physical health. From the perspective of mental health, for example, the addiction narrative rose above the rest. The respondents believed that both children and adults are at risk of becoming addicted to digital technologies very quickly, but they also believed that such an addiction can be quickly shed if a time limit rule is applied or if the use of digital devices is stopped altogether. At this point, it is important to remind ourselves to be sceptical about the addiction narrative prevalent in our social discourse, as it fits the description of moral panic (see also the article on social media by Rozgonjuk et al. in this chapter). Although participants in the DigiGen study also mentioned the potential of digital technologies for reducing stress and promoting well-being, these possibilities were clearly underutilised in the families studied.

As a rule, research participants associated the excessive use of digital tools with increased feelings of anxiety and nervousness.

For example, several mothers of toddlers aged 2 to 4 noticed that during the pandemic-related state of emergency, the children were often more nervous, aggressive, sleepy or lethargic, shouted more or became upset more easily than before. The respondents also felt that children were more disobedient, while their ability to play alone and use their imagination decreased. The parents related all this directly to the excessive use of digital tools.

MOTHERS’ DESCRIPTIONS OF THE EFFECT OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES ON THE BEHAVIOUR OF TODDLERS DURING THE PANDEMICRELATED STATE OF EMERGENCY

MOTHER 2: […] actually, it was noticeable that when using the phone for a long time, [the child] became more nervous; it changed them. Changed their emotions and maybe made them more aggressive. That’s when I realised: okay, now it’s too much.

MOTHER 3 For some reason, the younger one recently often complains about being bored. […] I can imagine how the digital world and these cartoons stimulate the brain, so to speak, and the ordinary world seems boring and slow and monotonous.

While the family members who participated in the DigiGen study often spoke of digital devices disrupting sleep and causing fatigue, the parents of toddlers who participated in the survey and the ethnographic study revealed that digital technologies and screen media are often used to support the child’s sleeping and eating routines. When discussing the dangers of digital technology, parents primarily perceived the risks related to physical health, mainly a decrease in children’s general physical ability or a deterioration of eye health. Less recognised was the threat to the child’s cognitive, social and emotional skills. At the same time, it is important to note that parents of toddlers were more concerned about the relationship between the child’s academic abilities and allowing or not allowing smart devices than about potential health risks. In other words, parents often expressed their lack of knowledge and concern about whether allowing a smart device too early might impair the child’s abilities or, conversely, whether introducing children to digital technologies later than their peers (e.g. from the age of seven, when the child starts school) could interfere with their development compared with peers.

Many parents use various parental mediation strategies to mitigate the mental and physical health risks associated with the use of digital technologies and to increase the benefits.

Parental mediation strategies can be divided into active and restrictive (Livingstone et al. 2017). Active mediation means that parents (or other people around children, such as teachers) provide social support to help children navigate the online world. Restrictive mediation, on the other hand, is related to various social and technical rules and restrictions that parents, teachers or other important people place on children’s technology use.

Studies show that five main strategies of parental mediation stand out:

active mediation of use (e.g. discussing content and sharing online experiences)

active mediation of safety (activities and recommendations related to safer and more responsible internet use)

restrictive mediation (establishing rules that limit time spent online and location of use, as well as content and activities)

technical restrictions (use of certain software or technical applications to filter, limit and monitor children’s online activity)

monitoring (checking the children’s online activities afterwards)

Which mediation strategy is implemented in any given family depends largely on family values, the parents’ attitudes towards internet use and how parents assess the role of digital technologies in the development of their children’s values (Kirwil et al. 2009). For example, studies conducted in Estonia and elsewhere confirm that the more active users of digital technologies the parents, the more their children also want to spend time in the digital world.

nologies the parents, the more their children also want to spend time in the digital world.

On the other hand, parents who could not enjoy the benefits of the modern world in their childhood are especially keen to introduce new technological opportunities to their children. The parent’s age, gender, socioeconomic status, experiences in childhood, education, media literacy and awareness of online risks, as well as the frequency and purpose of the parent’s use of digital technologies and their beliefs and convictions about the usefulness/harm of technology, play an important role in the choice of mediation strategies for children’s internet use (Kirwil et al. 2009). Parental mediation should therefore be seen as a set of practices intertwined with each other, which, in addition to other factors, are influenced by the parent’s cognitive abilities, communication skills, sociodemographic indicators and general ways of raising children (Kalmus 2013).

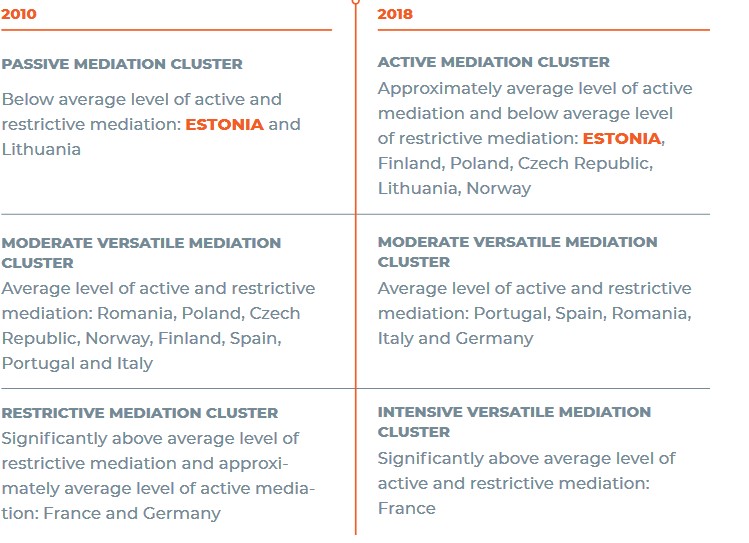

As a result of the analysis of the EU Kids Online survey, countries were divided into different categories by parental mediation strategies and by year as seen in (Table 4.4.1).

The analysis showed that the active mediation of both children’s internet use and safety has grown significantly in several European countries in recent years. For example, the results of the 2018 survey revealed that Estonian parents consider themselves to be active mediators of children’s internet use and safety. Most of the Estonian parents who participated in the survey stated that they talk with their children about what they do on the internet (92%) or give them advice on internet safety (59%) (Sukk and Soo 2018). However, the children themselves are much less aware of their parents’ activity in mediating their internet use. For example, only 54% of the Estonian children who participated in the study reported that their parents ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’ talk to them about what they do on the internet (Sukk and Soo 2018). Thus, the results reveal that children’s and parents’ perceived experiences of the frequency and activity of parental mediation do not match. According to children’s perceptions, parents have room to develop their parental skills.

According to the parents, the use of active mediation strategies took a back seat during the COVID-19 state of emergency, when many parents were busy with working from home as well as supporting distance learning and therefore could not actively monitor what their younger children were doing on digital devices or discuss what they saw with them. Interviews with mothers of 2-to-4-year-old children revealed, for example, that some parents began to implement technical mediation for the first time, using various technical aids (e.g. applications) to regulate children’s screen time and content.

Interviews with parents who participated in the DigiGen study also revealed that parents used restrictive mediation primarily to regulate the amount of time their children spent on digital media. Furthermore, automatically applied restrictions helped prevent conflicts between children and parents. At the same time, parents who often applied restrictive and technical mediation tended to over-regulate children’s use of digital devices and set limits where it was not necessary. The reported reason for the restrictions was to prevent potential health risks, such as damaging the eyes or the brain.

FAMILY MEMBERS’ STATEMENTS ABOUT RESTRICTIONS ON THE USE OF DIGITAL TOOLS

It is no longer possible to get him off this phone, only the time limit rule helps. (ET_F1_mother)

Yes, we have a rule that Mummy put a timer on my phone so that I could not play much. It’s about five minutes; well, about ten minutes or an hour. (ET_F1_child)

There is no such thing as sitting there for an hour straight. More like 15–30 minutes and then let’s move on to the next activity. (ET_F2_father)

I have limits on everything, even on what I don’t use… (ET_F10_child)

They say you shouldn’t use [digital tools] after 20:00, because then it’s evening and the brain and eyes are tired. So after 20:00 we do not use computers or anything like that. If necessary, cartoons, television on a large screen, but otherwise no phones, tablets, nothing. (ET_F9_grandmother)

However, the analysis of EU Kids Online survey data shows that the use of restrictive mediation strategies has clearly decreased among parents in Estonia and other EU countries that participated in the survey.

On the one hand, we can assume that the change is related to parents becoming more aware: restrictive mediation is often used by parents with lower digital literacy (Paus-Hasebrink et al. 2013). On the other hand, the decrease in restrictive mediation can be attributed to the impact of various Europe-wide interventions such as awareness-raising programmes, including the project Targalt internetis (Be Smart Online), which often emphasise the importance of active mediation and have developed training and guidance materials to help parents improve their skills. Although cultural differences between countries are still significant, the analysis shows that parents are using restrictive mediation less and instead actively guide and support children’s internet use.

In 2010, 71% of Estonian parents who participated in the EU Kids Online survey applied an active mediation strategy. In 2018, 87% of the parents who participated in the survey did so. Across both indicators, Estonian parents were still below the European average, which was 78% (2010) and 89% (2018), respectively.

Several studies analysed for our article showed that if there are any rules related to digital technologies in the family, they are mainly established by parents. Children’s opinions and suggestions are usually not asked for or considered. At the same time, children are highly interested in adding their own ideas and opinions to family agreements and want to be included in this process as equal participants. It is often the children who teach and correct their parents when they misuse digital technologies or break agreements.

‘Mummy, you can’t use the phone in the car’ or whatever, right. It is very disciplining. (ET_F7_ mother)

The children claimed that even if the rules within the family were not overly popular, they were still good and necessary.

Data from several studies reveals that parents combine different mediation strategies and adopt different parental roles depending on the specific context. Among the families that participated in the DigiGen study, making rules is an ongoing process spurred by specific situations – parents develop rules through trial and error.By contrast, the parents in the family that participated in the ethnographic study had agreed that the father mainly guided the children’s use of digital technologies, while the mother did household chores (like cleaning and cooking). However, as with the participants in the DigiGen study, the father chose mediation strategies according to the specific situation. For example, whenever the father had the energy and interest to support the children’s use of digital tools, he either explained things to the children and discussed media content with them or introduced the children to new environments and activities on the screen, seeking to broaden the children’s media knowledge. As an active mediator, the father would willingly take on the role of a guide, but when he wanted to watch a TV show or surf on his smartphone, digital tools played the role of a babysitter for the children.

In addition to establishing family agreements, both parents must adhere to these agreements. Problems arise when one parent has set rules (e.g. limiting the child’s time spent using digital devices or the content they are allowed to view) and the other parent does not adhere to them. The interviews with the mothers of toddlers revealed that parents’ principles and understandings on these issues tend to diverge, especially when the parents live apart. Differences in such agreements can cause confusion for toddlers, especially if, for example, one parent places limits on their use of digital technology and the other does not.

However, the parents who participated in the research agreed almost unanimously that children need the support and help of parents and other family members in the digital as well as the physical world. They also sensed that such support was equally important for the mental well-being of children and parents alike. At the same time, parents blame digital technologies to some extent for creating new challenges in parenting. Though parents can rely on intergenerational experience when guiding their children in the ‘real world’, in the digital world, such a collective experience across generations is not yet available. This is why parents often feel helpless and in need of more advice on how to better support their child’s use of digital technologies and reduce the associated potential risks. Such uncertainty stems in part from the fact that many parents still feel inferior to their children in digital skills. Thus, children are often trusted to use digital tools on their own, or older siblings are tasked with mediating younger children’s use of digital technologies.

TEN RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PARENTS ON ENSURING THE APPROPRIATE USE OF THE INTERNET AND SMART DEVICES BY THEIR CHILDREN

- Remember that what you’ve taught your child about being a good person also applies in the digital world.

- Lead by example rather than words.

- The ability to cope in the digital world is vital and is something that has to be learned.

- Decide which websites you want your child to be visiting.

- Set some ground rules with your child about using the internet and smart devices and make sure all of you follow them.

- Do things together in the digital world.

- Make sure you know how social media works.

- Use the same social media as your child but respect their privacy.

- Always try to understand before judging.

- And remember – computers and smart devices are no substitute for parents!

Source: „Targalt internetis“ (www.targaltinternetis.ee/lapsevanematele/)

Summary

Digital technologies play a central role in the everyday life of Estonian families, and people believe their use shapes mental health and well-being. Digital technologies became irreplaceable during the social isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, when work, education and social life – and thus the general well-being of families – directly depended on the availability of digital tools and the family members’ knowledge of various technological possibilities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the time spent in front of screens increased significantly in many families. While parents working from home and children on distance learning had to spend countless hours in front of the computer because of work- and school-related obligations, digital technologies became a necessary babysitter for many toddlers. Even though, as a rule, Estonian parents consider themselves to be quite competent mediators of their children’s internet use and safety, the state of emergency caused declared during the pandemic seriously tested parents’ ability to actively mediate children’s use of digital technologies in stressful situations and undermined previous family agreements regarding the use of digital technologies – for example, rules on limiting the time spent using digital technologies. However, such rules, ideally agreed on between parents and children, are like a benchmark of common family values and views, and their absence can cause unnecessary tensions and conflicts between family members.

The studies confirm that Estonian families implement family agreements and various parental mediation strategies to minimise the risks related to the use of digital technologies, for example, to prevent the excessive use of digital tools. Research shows that parents are mainly aware of the risks to their child’s physical health but their awareness of the emotional, social and cognitive risks associated with the use of digital technology is still rather limited. Thus, awareness-raising programmes (e.g. Targalt internetis), which over the years have significantly contributed to changing parental mediation behaviour and attitudes, should now pay more attention to the known mental health risks posed by technology use.

Kalmus, V. 2013. Making sense of the social mediation of children’s internet use: Perspectives for interdisciplinary and cross-cultural research. – Wijnen, C. W., Trültzsch, S., Ortner, C. (eds.). Medienwelten im Wandel. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 137–149.

Kalmus, V., Sukk, M., Soo, K. 2022. Towards more active parenting: Trends in parental mediation of children’s internet use in European countries. – Children & Society, 36(5), 1−17. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12553.

Kapella, O., Sisask, M. 2021. Country reports presenting the findings from the four case studies – Austria, Estonia, Norway, and Romania. DigiGen working paper series No. 6. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19070090.

Kirwil, L., Garmendia, M., Garitaonandia, C., Martínez Fernández, G. 2009. Parental mediation. – Livingstone, S., Haddon, L. (eds.). Kids Online: Opportunities and Risks for Children. Bristol: Policy Press, 199–215.

Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., Helsper, E. J., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Veltri, G. A., Folkvord, F. 2017. Maximizing opportunities and minimizing risks for children online: The role of digital skills in emerging strategies of parental mediation. – Journal of Communication, 67(1), 82–105.

Nevski, E. 2019. 0–3-aastaste laste digimäng ja selle sotsiaalne vahendamine. Doktoritöö. Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikool. https://www.etera.ee/zoom/57708/view?page=3&p=separate&tool=info.

Paus-Hasebrink, I., Bauwens, J., Dürager, A. E., Ponte, C. 2013. Exploring Types of Parent–Child Relationship and Internet use across Europe. – Journal of Children and Media, 7(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2012.739807..

Sahk, P. 2021. Vanemate vaade 2–4-aastaste laste ekraanimeedia kasutusharjumuste muutustele COVID-19 eriolukorra ajal ja selle järgselt. Magistritöö. Tartu: Tartu Ülikool. https://dspace.ut.ee/handle/10062/72535.

Stoilova, M., Nandagiri, R., Livingstone, S. 2019. Children’s understanding of personal data and privacy online – A systematic evidence mapping. – Information, Communication & Society, 24(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.16571 64.

Sukk, M., Siibak, A. 2021. Caring dataveillance and the construction of ‘good parenting’: Reflections of Estonian parents and pre-teens. – Communications, 46(3), 446–467. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2021-0045.

Sukk, M., Soo, K. 2018. EU Kids Online’i Eesti 2018. aasta uuringu esialgsed tulemused. Kalmus, V., Kurvits, R., Siibak, A. (toim). Tartu: Tartu Ülikool, ühiskonnateaduste instituut.

Vihalemm, P., Lauristin, M., Kalmus, V., Vihalemm, T. (toim) 2017. Eesti ühiskond kiirenevas ajas. Uuringu „Mina. Maailm. Meedia“ 2002–2014 tulemused. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.