Climate concern as a mediator in people’s relationship with the environment

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a dire warning to humanity about the state of the climate and the failed attempts to prevent anthropogenic climate change. These statements were published at a time when extreme weather events such as heat waves, wildfires and floods were becoming more frequent. Studies of attitudes in various parts of the world (including Estonia) show that people’s willingness to understand climate-related future scenarios and relate these to their own future has increased significantly. It has also become apparent that societies are not decisively dealing with this urgent problem.

It has also become apparent that societies are not decisively dealing with this urgent problem. The words and actions of climate-concerned members of society, including their formation into interest groups, put them increasingly at odds with more passive democratic processes, expressed mainly through voting in elections.

This article aims to offer a multifaceted view of a situation in which some people are acutely aware of the dangers of climate-related changes yet have to look for solutions amid diminishing but still widespread indifference. The article first describes people’s attitudes to climate and some worrying implications for human behaviour. This is followed by an analysis of the experiences of climate-concerned people in Estonia, to find out how greater awareness can have a life-changing effect. We describe a new sociality emerging from climate concerns, which has a stimulating and supporting impact on mental health and well-being.

Our analysis is based on statistical data and on sociological and anthropological research related to climate concerns. We have conducted this type of research since 2019. This data comes from ethnographic fieldwork on social media and real-life participant observations among representatives of climate and environmental movements, as well as from interviews with more than 30 activists. Some of the quotes are from Anna Silvia Seemel’s bachelor’s thesis (Seemel 2021).1 Most of the interviewees are involved in the Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion movements and mainly come from the largest Estonian cities.2

Natural disasters caused by climate change can trigger psychological problems that manifest as sadness, anxiety, distress, grief, anger, depression, stress or other emotional states. (Stanley 2021; Cunsolo Willox and Ellis 2018). These feelings have been described using new terms such as ‘solastalgia’3. (Galway et al. 2019) or ‘pretraumatic stress disorder’ (Kaplan 2015). The impact of climate change on our mental health is the subject of climate psychology, a new sub-field of ecopsychology (Climate Psychology Alliance 2020).

Forward-looking emotions related to the global climate crisis, the threat of environmental catastrophe, and the resulting uncertainty have so far been described in Estonia as ‘climate anxiety’ or ‘eco-anxiety’. But anxiety does not necessarily entail a link between a perceived threat and a subjective feeling; it can be interpreted as a subjective negative emotion that is not necessarily related to a real threat. However, climate issues are not a matter of subjective feeling or a mental health disorder but a ‘real-life stressor’ (O’Brien and Elders 2021). The term ‘climate anxiety’ obscures the fact that there is a real and serious problem behind the emotional response. Those concerned about climate change perceive the term ‘anxiety’ as implying powerlessness and weakness and undermining agency and ability. The terms ‘climate grief’, ‘climate fear’ and ‘climate concern’ are considered far more appropriate and empowering.

A review of the vocabulary used is also necessary because of its social implications. One reason climate-conscious people are concerned is the experience that much of society does not take the climate problem seriously enough. Downplaying the concern by labelling climate-conscious citizens as ‘anxious’ does not support them in their search for solutions. Instead, it reduces their ability to overcome concern- and fear-induced apathy or panic and seek like-minded people to find solutions. If society refers to the problem as imaginary rather than real, and there is no understanding of the need for wider action, then climate concern may indeed become an actual mental health problem in an indifferent and judgmental environment. (O’Brien and Elders 2022, Pihkala 2020). On the other hand, wider societal understanding and

recognition of the problem of climate change and the need to act on its solutions can mitigate risks to mental health, mobilise people to address the problem and build resilience.

For these reasons, we use the term ‘climate concern’ throughout the article to refer to a justified stressful concern about real threats from climate change. It aptly points to a reality that causes such feelings.

Climate change, the cause of climate concern, differs in several ways from other environmental problems affecting mental health. (Pihkala 2020). First, climate change is a global and systemic problem. Unlike air pollution or noise, the changes that come with it are not necessarily perceptible locally. Local weather conditions do not provide a clear understanding of broader climate processes, and even less of the future changes in a particular place. But we still need to mitigate climate change, although actions by any individual society towards changes in the economy, politics or everyday life are insufficient to slow down climate change.

Another aspect of the problem is that it is still developing and lies mainly in the future. This can increase fear, as even the best models cannot fully predict the future. The fate of human societies in such a situation is also unpredictable. In Estonia, where there is relatively little direct experience of climate change, climate concerns are primarily mediated by the media and political decision-makers. People experience it as a concern, abstracted from fragments of information, about the loss of hope for the future and the imminent arrival of dire consequences.

In this way, climate concern depends on whether and how public discussions address scientific and abstract problems and translate them into everyday language. More broadly, it also depends on the extent to which science is understood and trusted as a coherent reflection of reality, and the ability of science to create adequate models of the future. The similarity of the messages from different branches of science also plays a role (e.g. both climatologists and biologists can see the consequences of climate change), as do the quality and scope of the translation of abstract scientific messages into everyday language, and the level of scientific education of the population. Unlike specific, locally measurable parameters of environmental pollution, climate change – which is global, future-related and abstract – requires an explanation that enables the whole society to begin to understand the problem. This includes those on whom the solution to the problem depends (especially in terms of their production and consumption practices) but who are shielded from societal expectations and demands for change.

Most climate-conscious citizens are critical of the existing economic system and social structures because these are seen as the main sources of the climate problem. .

They do not regard economic growth as a positive trend; they are aware that it leads to increased climate risks and depleted natural resources. Their climate concern is triggered by the experience that social institutions are most likely unable to manage and prevent the climate problem, as they cannot function outside the capitalist economic system and growth ideology. Because of this, they see climate change as a ‘super-wicked’ problem (Gillighan and Vanderbergh 2020), it must be solved in a limited time frame, it cannot be centrally controlled, its potential solvers are also the cause of the problem, and the solution is held back by irrationally continuing policy choices (Levin et al. 2012). PThe super-wickedness of the problem also lies in its entanglement with many other problems, and understanding this leads one to seriously doubt that the existing economic system can cope with the problems it has caused, offering merely greenwashing and ‘technofixes’ as solutions.3.

As a result, climate-concerned people change their economic behaviour, focusing on consumption and lifestyle, which from this point of view is the only conceivable course of action both on the economic and personal level. Striving to prevent the consequences of climate change means new choices and new plans for the future. This behaviour can be seen both as adaptive and as offering mental balance, because it resolves the dissonance between conventional participation in the climate-destroying economy on the one hand and climate concern on the other.

The level of climate concern varies by country and depends on the local circumstances: the climate sensitivity of the region, the threats that are publicly discussed, the socioeconomic situation, environmental attitudes and perceptions of human impact on the environment, and the views of opinion leaders. (Plüschke-Altof et al. 2020). Like everywhere in the world, climate concerns are on the rise in Estonia. An environmental awareness survey of the Estonian population (Turu-uuringute AS 2020) indicates that while only 10% of the population considered climate change a serious problem in 2016, by 2020 this figure had increased to 18%. A similar situation is confirmed by a recent European Investment Bank survey (EIB 2022) according to which 19% of people in Estonia considered climate change a serious problem.

The results of the European Social Survey (2016) indicate that concern among Estonian people is lower than the European average (see Figure 5.1.1). At first glance, the situation could be associated with Estonia’s climatic region, which is less affected by extreme weather conditions.

climatic region, which is less affected by extreme weather conditions. Figure 5.1.1 shows, however, that Estonia’s level of concern is not in the same group with the climatically similar Nordic countries but is rather closer to that of the other former Eastern Bloc countries.

J5.1.1.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-24

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

library(scales)

#faili sisselugemine

J511=read.csv2("PT5-T5.1-J5.1.1.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

J511$Keskmine.kliimamurelikkuse.tase..1.5.skaalal.=as.numeric(J511$Keskmine.kliimamurelikkuse.tase..1.5.skaalal.)

names(J511)=c("X","Y")

J511$X[5]="ESTONIA"

J511$X=as.factor(J511$X)

J511$X=factor(J511$X,levels(J511$X)[order(c(5,4,1,2,3))])

font=c(1,1,1,1,2)

ggplot(J511)+

geom_col(aes(x=X,y=Y,fill=X),width = 0.7)+

geom_label(aes(x=X,y=Y-0.1,label=Y),cex=3.5)+

theme_minimal()+

coord_flip()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#295200","#295200","#295200","#295200","#8fa300"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

xlab("")+

ylab("AVERAGE SCORE ON A SCALE OF 1–5")+

theme(legend.position ="none",axis.text.y = element_text(face=font))+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,5),breaks=c(0:5))## Warning: Vectorized input to `element_text()` is not officially supported.

## ℹ Results may be unexpected or may change in future versions of ggplot2.According to a European Investment Bank survey (EIB 2020), (EIB 2020) there are many more men (20% in Estonia; 10% in Europe) than women (12% in Estonia; 7% in Europe) who do not admit that climate change is real. Estonian men and women also differ in terms of their levels of doubt about the anthropogenic nature of climate change (29% of men and 16% of women doubt it) and the extent to which their behaviour can influence climate change (55% of Estonian men and 31% of women do not believe that they can make an impact). On average, a higher percentage of people in Estonia (42%) than in Europe on average (31%) do not believe that their behaviour can affect climate change to any significant extent or at all.

Only 10% of the Estonian population think that climate change affects their daily life, while 17% do not think that even their children’s lives could be affected by climate change. However, the percentage of all those who think that climate change affects their everyday life at least somewhat is considerably higher: 72%. In this respect, Estonians are clearly in the same group with the other climatically similar Northern European countries and share the belief that their location protects them against extreme climate events.

An Estonian environmental awareness survey (Turu-uuringute AS 2020) describes the main perceived threats caused by climate change and the respondents’ assessment of the state’s capacity to handle these threats (Figure 5.1.2). Over time, the threats have begun to be recognised as more important, while the percentage of people who doubt the state’s ability to cope with extreme climate events has also risen. Those worried about the state’s ability to respond are more often older people, Estonian-speakers, residents of small towns and settlements, and residents of central and southern Estonia.

J5.1.2.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-24

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

library(scales)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J532=read.csv("PT5-T5.1-J5.1.2.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J532)=gsub("X", " ", names(J532))

J532=pivot_longer(J532,2:3)

names(J532)[1]="Faktor"

J532$Faktor=as.factor(J532$Faktor)

J532$Faktor=factor(J532$Faktor, levels(J532$Faktor)[order(c(2,4,3,1))])

#joonis

ggplot(J532)+

geom_col(aes(x=Faktor,y=value,fill=name),width=0.7,pos=position_dodge(0.8))+

theme_minimal()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#8fa300","#1E272E"))+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,60))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")+

scale_x_discrete(labels = wrap_format(25))+

theme(legend.title=element_blank(), legend.position = "bottom",)(Turu-uuringute AS 2020)

One might assume that indifference to climate change reflects socioeconomic difficulties and deprivation, such as the inability to find the mental energy to deal with the issue. However, the European survey does not show that indifference significantly increases with low income. Rather, the share of climate change deniers and those who doubt the anthropogenic origin of climate change is somewhat larger among people with higher incomes. The income gap is particularly clear when it comes to being concerned about extreme climate events – low income increases concern and the feeling that individual behaviour has little effect. These differences are even more striking against the absence of such an income gap in the European average attitudes (Figure 5.1.3). The results of the European survey (EIB 2022) also reveal that Estonian residents rank fourth in terms of their fear that green policies may reduce their purchasing power.

J5.1.3.R

maiko.koort

2023-07-24

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

library(scales)

#faili sisselugemine ja andmete formaadi korrigeerimine

J533=read.csv("PT5-T5.1-J5.1.3.csv",header=TRUE, encoding ="UTF-8")

names(J533)=gsub("\\.", " ", names(J533))

J533=pivot_longer(J533,2:5)

J533$X=as.factor(J533$X)

J533$X=factor(J533$X, levels(J533$X)[order(c(2,1,3,4))])

J533$name=as.factor(J533$name)

J533$name=factor(J533$name, levels(J533$name)[order(c(2,3,1,4))])

#joonis

ggplot(J533)+

geom_col(aes(x=X,y=value,fill=name),width=0.7,pos=position_dodge(0.8))+

theme_minimal()+

scale_fill_manual(values=c("#8fa300","#0069AD","#295200","#1E272E"))+

theme(text = element_text(color="#668080"),axis.text=element_text(color="#668080"))+

scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0,60))+

xlab("")+

ylab("%")+

scale_x_discrete(labels = wrap_format(20))+

theme(legend.title=element_blank(), legend.position = "bottom")+

guides(fill=guide_legend(nrow=2,byrow=TRUE))A European survey (EIB 2022) indicates (EIB 2022) that 67% of Estonian residents are convinced that they are doing everything they can in their daily lives to fight climate change. At the same time, only 35% believe that their fellow citizens are doing the same. This difference in opinion is especially significant when compared to other countries: overall, these differences are larger in Southern European countries and smaller in Northern Europe. K The dissonance between experiencing climate change and perceiving fellow citizens’ willingness to change probably creates frustration in people, which is greater in Southern Europe, where the changes are more clearly felt. Estonia is quite exceptional among northern countries: given Estonia’s location and background, our indicators should be lower than those of Lithuania and Latvia, but they are not. Unfortunately, the quantitative data do not explain Estonians’ greater mistrust towards their fellow residents’ willingness to act.

Climate concern has tangible consequences, and a willingness to change one’s behaviour for the sake of the climate is also relatively common in Estonia:

- 14% o have already decisively reduced or stopped eating beef

- 38% buy local food products

- 27% cycle or walk (19% do so based on climate considerations)

- 13% no longer have a car

- 20% spend holidays in Estonia or nearby

- 24% do not fly

At the same time, there is a striking proportion of those who do nothing, and intend to continue doing nothing, for the sake of the climate:

- 37% do not intend to reduce their consumption of beef based on climate considerations

- 27% do not want to start buying local products

- 19% do not plan to reduce car use

- 32% do not intend to start using public transport

- 40% do not intend to fly less

- 50% do not intend to give up their dream holidays in faraway destinations

Given these patterns, seriously concerned residents are likely to feel that fellow citizens do not share their concerns.

We looked at ethnographic data to get an insight into climate concern: how the caring or indifference, inaction or action around us affects the climate-concerned and what that concern or fear means to them. Distinguishing those who are seriously concerned about the climate from the rest of the population is not easy, as other people’s indifference to the climate problem makes it difficult to express one’s concern. A person’s immediate social circle can be downright hostile to their worries. In the past three or four years, the topic has become more recognised, but with the emergence of new global climate movements, their representatives and participants have also come under criticism from the press as well as social media. Some of those concerned conceal their anxiety, while others talk about it only in a narrow circle. Here we look at people who express their climate concerns quite clearly – for example, by participating in groups focusing on the future of the climate and environment. Studying these people allows insight not only into the concern itself but also into the action that stems from it.

Mental health issues make up the framework of this article, but we do not approach them from a psychological perspective. Instead, we view climate concern as a mental health-related experience that mediates human relationships and is linked to people’s actions and perceptions of the environment and the future.

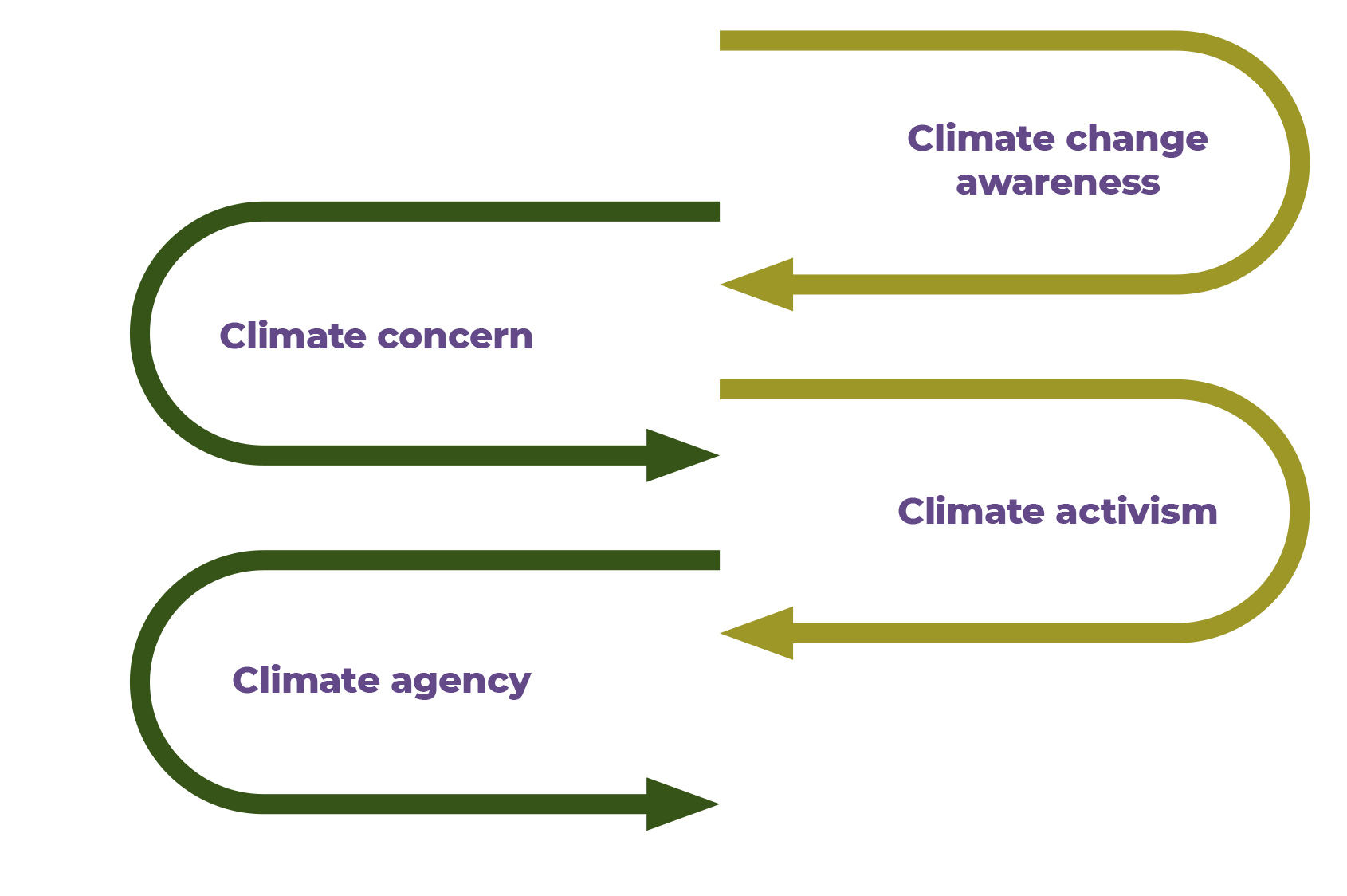

Experiencing climate concern is an important step towards climate agency(Pearse et al. 2018, lk 340–342) that is, towards the ability to act against climate change. Climate agency involves overcoming the abstractness of climate problems so that people start looking for specific ways to find solutions and for support networks (see Figure 5.1.4).

For many of the climate-concerned people in our study, their first exposure to climate issues was information about scientific data in the media and social media. The new knowledge triggered their desire to search for more information, which in turn opened their eyes to the complexity of the problem and the imminence of the threats. This experience can be world-changing. One of our youngest respondents states: „… ‘When I became aware [of the climate issue] six months ago, [I realised] that you will deal with it for the rest of your life’ (Gerli4, 17). Another young interviewee describes her and her family’s concerns about the burden she has taken on: ‘At the same time, I can’t live any other way anymore; now I think more globally, and it’s hard for me not to do that. There is no way back from this’ (Mai, 19).

Several interviewees point out that their first encounters with climate problems brought along negative emotions: sadness, despair, depression and anger. Over time, these have turned into acceptance. Emotions can change across a wide range and in waves,

and many describe their fear as a developing process. For example, in the beginning, „ there was ‘depressing, overwhelming knowledge, which turned into anger at some point. [—] Then there was acceptance, and then I studied even more deeply, and a new wave of depression arose from it’“ (I5, 22: Seemel 2021). A part of the fear is purely existential. As Häli (16) says,„… ‘maybe I’ll just die at the age of 30 because of … some kind of climate change effect.’“ On the other hand, fear motivates action: „‘Fear is a very big motivator for me and why I am involved in climate activism in the first place. I don’t want to live in the kind of future world that is currently being predicted’“ (Alvar 20).

Among the interviewees, the feeling of being alone with their concerns increases their fear. While social media groups partly relieve the fear, personal interaction with like-minded people is mostly the privilege of big-city dwellers and people already living in environmentally-minded communities. While statistics show a fair share of concerned people, there is still only a small percentage of people at the ‘extremely concerned’ end of the scale, and they may not necessarily reach each other if they live in small towns or in the countryside, or if they don’t use social media.

Extreme concern for a global problem that requires the effort of all humanity makes the burden especially heavy for a small group to bear.

The level of concern is therefore related to a lack of opportunity to share it and the sense that fellow citizens value their comfort more than a safe future „.‘[They] just don’t want to change themselves … it’s more convenient as it is, it’s so convenient to continue their lives and […] not just […] want to let it go and not drive a car anymore’“ (Anna, 16).The indifference of other people increases the concern: „… ‘[They] don’t seem to understand the real consequences, how their own lives are affected, right? No one can see that connection’“ (Gerli, 17). Seventeen-year-old Kadri describes her conflicting feelings between the carefree public and her own awareness. „[—] as something she has come to call ‘a schizophrenic feeling. On the one hand, I read in the IPCC report that the time for climate change [mitigation] is running out and we are on the way to a major crisis, and then I look around me, and people are so calm, they still barbeque several hundred grams of meat per person and buy new cars and bigger houses and no one cares at all. And then you get this feeling of living in parallel worlds, and it’s actually quite terrible from time to time.“

Being concerned can isolate a person from others if the others consider the topic trivial. In such a context, a climate-concerned person tends to feel that talking about climate change only annoys and irritates other people. Several respondents mention such an experience, for example:„[—]‘I don’t want to push the environmental issue so much on people, because […] they probably wouldn’t like me very much, because it would be annoying’ “ (Häli, 16).

The gap between understanding climate change as a problem and taking action to prevent or mitigate it is something the climate-concerned are keenly aware of. They state that even those who accept and take the problems seriously ‘cannot grasp the idea that they should make changes in their lives or give something up to deal with the problem now. They are ready to take action if it is beneficial and convenient for them, fits into their schedule and does not take time away from other activities’(Viire, 30).

The fieldwork shows that one pervasive fear is that of a lost or uncertain future: ‘I don’t know at all what the future will bring […] that’s why it’s so scary, it’s very unstable, we don’t know what can happen,’ says Alvar (20). For younger respondents, whose life path choices are in the formative stage, the distortion of future opportunities due to climate change is depressing: … ‘All the previous thoughts I had are of little use if the climate goes to hell, because whatever I will be doing, I will be doing it in an environment that has climate in it’ (Kadri, 17). According to several climate-concerned respondents, their pre-climate awareness visions of the future have disappeared, become meaningless or ‘frozen’, put on hold: „… ‘The whole picture of the world that I had of my future, […] in fact it basically no longer exists […] Right now […] I feel like I can’t make any plans for my life’ (Anna, 16).

The feeling that they are living with a worrying future is shared by all climate-concerned people. Uncertainty is another part of the fear. Uncertainty, and the inability to determine when and how climate processes can have a direct impact on the person themselves, are sources of distress for the participants in the study. Many are thinking about future scenarios of social collapse, caused directly or indirectly by the impact of climate change.

amid an indifferent, complacent society that sticks to its old way of life.

However, preparing for the end of the world, so to speak, is strangely alienating and frightening amid an indifferent, complacent society that sticks to its old way of life.

The concerned have to face an uncertain future so often that they somehow manage to overcome their fear and find some peace in themselves: ‘On the one hand, I am afraid that the system will collapse, and on the other hand, I hope that it will collapse as quickly as possible […] The faster it collapses, the faster it will be possible to build something more functional’ (Marek, 26).

Thinking of climate concern as climate anxiety has meant that climate awareness is associated with the psychological problems that anxiety can lead to. Yet for our subjects, climate awareness is the path to climate agency, through which a person can manage, confront and act upon their fear. Behind climate agency is a clear understanding that climate change is the most crucial issue of our time, and a determination to take it with the seriousness it deserves. The related life changes include climate activism – seeking knowledge and solutions, informing others and publicly demanding solutions.

Although dealing with climate and environmental issues can cause deep sadness or anguish, those who have reached this point feel grateful for the knowledge gained. Awareness is a value we can build on to prepare for the future: ‘Whatever it was at the beginning, it was a real pain – but now I feel like I’m several steps ahead in my thinking. I have knowledge that I can share with others. And I can work in the name of better human relationships, before society falls apart […]’

´Whatever it was at the beginning, it was a real pain – but now I feel like I’m several steps ahead in my thinking. I have knowledge that I can share with others. And I can work in the name of better human relationships, before society falls apart […]’[—]“ (Tiia, 46).

For decades, there have been warnings against presenting too-bleak future scenarios on the climate issue, as the resulting despair can lead to apathy or even denial of anthropogenic climate change. However, it is precisely in the era of talking about the climate crisis instead of climate change that citizens have rapidly mobilised (Reichel et al. ilmumas). It was the ominous message about the climate crisis that brought hundreds of young people to strike outside the Estonian Parliament building as part of the World Climate Strike in March 2019

Although fellow citizens have regarded the climate-active youth as an anxious, panicked group whose mental state should raise society’s concern and who also contribute to the anxiety of bystanders, their activism can also be viewed from a completely different angle. Concern and fear often lead to activism, which helps overcome the concern and leads people into calmer waters. Activism offers a kind of support group with whom the aspects that cause concern and anxiety can be safely discussed. Moreover, the fact that the group aims to solve a problem allows its members to turn their concerns into energy for action. This in turn increases mental resilience (Pihkala 2020).

Shared concern is motivating and empowering, and international reach in climate activism gives it an additional dimension: [—] ‘We all have similar fears and hopes and concerns as regards climate and activism. It is even more empowering somehow, especially the international dimension, the feeling that we all come together, we all have the same goal. It was very life-changing for me’ (Mai, 19). Participating and acting in a group relieves the fear that no one else cares about the issue and is ready for change, as well as the feeling that all action is futile. Fear can be seen as a life-changing catalyst, and the mental state of the climate-concerned does not necessarily amount to being passive or giving up.

In addition to having a support group and enthusiastic agency, participants in climate movements benefit from an awareness of the importance of mental health.

Climate movements started from people’s concerns, which also means that people are aware of the implications of the issue for their mental well-being. Several climate groups have focused on mental balance: ‘Certainly, being climate activists, we have a stronger argument or a stronger motivation to avoid this kind of burnout thing, because the point of this whole thing is sustainability, both in the world with nature and so on, and in the movement itself …’ (Mai, 19). Self-analysis is also important for understanding the role of activism in the balance: ‘Remaining calm at the same time, not being crushed by everything that is happening. I guess sometimes I used to have a hard time being active seeing how bad everything is’ (Anna, 16).

The same thinking is supported by an activist speaking specifically about mental health: … ‘I’ve come across people with crazy traumas, but I understand that it’s just such an emotional topic. […] That’s why I’ve gone a little bit in the direction where I’m really interested in maintaining mental health…’ (Cäthy, 30).The balance is also maintained by placing limits on how much to deal with topics that can aggravate the concern: … ‘We have a rule that we can talk about these topics for maybe two hours a day, and then we stop and start talking about sports or something. You can’t live in it all the time’ “ (Artur, 31).

Thus, participating in climate-conscious groups – both in-person and virtual – helps on many levels. First, it helps that the object of concern is dealt with by searching for information and the best solutions. Second, it provides a supportive social environment where people work together to solve the problem. Third, mental health issues are consciously addressed in such environments.

Summary

Climate concern means awareness of a global, systemic, future-related problem that societies and fellow citizens are not addressing seriously enough. Although there are not many extremely climate-concerned people, an increase in awareness is a clear trend, influenced by both information on climate-related disasters in the world and personally experienced changes in the weather. The rising climate concern is not a passive panic that ends up causing apathy; instead, it leads people looking for relief to seek out new knowledge and groups that share relevant knowledge and offer outputs for action.

As such, climate concern is a path to climate agency and the possibility of channelling one’s concern into new social relations and activities, which in turn help shape the situation and general trends. Therefore, it is not a mental health problem but a solution-seeking adaptation process motivated by a real problem.

However, it should be kept in mind that the path to climate agency cannot be taken for granted. It is important from the mental health perspective that for some people, climate anxiety in its different stages reduces the ability to cope, and they risk developing mental health problems. This is especially so for those who cannot find a way to share and redirect their concerns. Mental health problems arising from climate concern are signs that something is wrong in the relationship between humans and the environment. The whole society should pay attention to this, not just those who experience it more acutely..

Concern or fear in the face of danger is an adequate response, as is seeking social support in such a situation.

Climate-conscious people are usually also aware of the importance of maintaining mental health. Taking climate change and environmental damage seriously and implementing solutions to it should be a common goal for Estonian society. Then climate change adaptation can truly be tackled. And this in turn will help alleviate the tangible consequences of climate change, while also supporting science-based environmental and climate awareness, encouraging climate-concerned people to come together and act towards a common goal, and promoting these people’s mental health in the process.

Climate Psychology Alliance 2020. The Handbook of Climate Psychology. Climate Psychology Alliance. https://www.climatepsychologyalliance.org/index.php/component/content/article/climate-psychology-handbook?catid=15&Itemid=101.

Cunsolo Willox, A., Ellis, N. R. 2018. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. – Nature Climate Change, 8, 275–281.

EIB 2020 – European Investment Bank 2020. The EIB Climate Survey 2019–2020 Database. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank.https://www.eib.org/en/surveys/2nd-climate-survey/index.htm.

EIB 2022 – European Investment Bank 2022. The EIB Climate Survey: Citizens call for green recovery. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank.

ESS8 2016. Public Attitudes to Climate Change. European Social Survey. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/themes.html?t=climatech.

Galway, L. P., Beery, Th., Jones-Casey, K., Tasala, K. 2019. Mapping the solastalgia literature: A scoping review study. – International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2662.

Gillighan, J. M., Vanderbergh, M. P. 2020. Beyond wickedness: Managing complex systems and climate change. – Vanderbilt Law Review, 73(6), 1777–1810.

Kaplan, E. A. 2015. Climate Trauma: Foreseeing the future in dystopian film and fiction. New Brunswick (NJ), London: Rutgers University Press.

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., Auld, G. 2012. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. – Policy Sciences, 45(2), 123–152.

O’Brien, A. J., Elders, A. 2022. Editorial: Climate anxiety. When it’s good to be worried. – Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29, 387–389.

Pearse, R., Goodman, J., Rosewarne, S. 2010. Researching direct action against carbon emissions: A digital ethnography of climate agency. – Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2(3), 76–103.

Pihkala, P. 2020. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. – Sustainability, 12(19), 7836.

Plüschke-Altof, B., Vacht, P., Sooväli-Sepping, H. 2020. Eesti noorte keskkonnateadlikkus antropotseeni ajastul: head teadmised, kuid väike mure? – Allaste, A.-A., Nugin, R. (toim). Noorteseire aastaraamat 2019/2020. Noorte elu avamata küljed. Tallinn: Eesti Noorsootöö Keskus, 57−73.

Reichel, C., Plaan, J., Plüschke-Altof, B. ilmumas. Speaking of a climate crisis: Shared vulnerability perception and related adaptive strategies of the Fridays for Future movement. – Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research.

Stanley, S. K., Hogg, T. L., Leviston, Z., Walker, I. 2021. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. – Journal of Climate Change and Health, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100003.

Turu-uuringute AS 2020. Eesti elanikkonna keskkonnateadlikkuse uuring. Tallinn: Keskkonnaministeerium, Tallinna Ülikool.