1.5

Activities and services supporting mental health in Estonia: the current situation and development needs

Approximately every fifth person worldwide experiences a mental health disorder every year(Steel et al. 2014), For Estonia’s population size, this equals to about 260,000 people yearly. Between 2016 and 2020, more than 140,000 people in Estonia had a mental disorder cited as the primary or concomitant diagnosis on their treatment bill. This suggests that more than 100,000 people do not seek or receive help for their mental health problems from the healthcare system. According to the OECD, Estonia annually loses 2.8% of its GDP, or 572 million euros, due to mental health problems(OECD 2021).

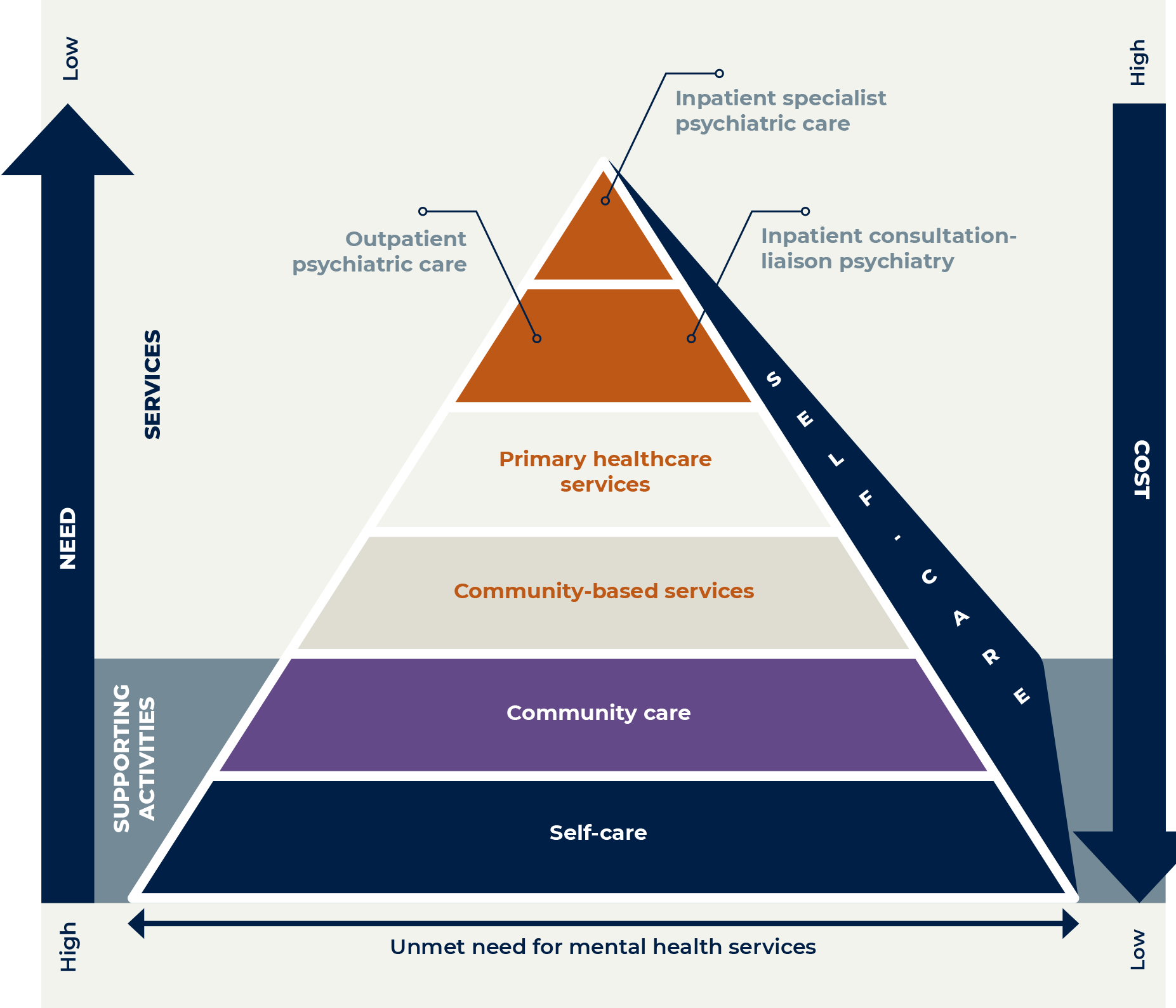

The Green Paper on Mental Health presents a vision of an optimal distribution of mental health services and supporting activities.(Sotsiaalministeerium 2020a; Figure 1.5.1). The pyramid diagram in Figure 1.5.1 shows that the greatest need is for lower-level interventions, such as self-care and community-based services that support mental health. Specialist care is placed on the highest level in the hierarchy of services, as it is expensive but less widely needed if the lower levels function effectively.

The core problems with the mental health services system in Estonia are the fact that care pathways1 are fragmented and complex, there is a shortage of specialists, cooperation is lacking and the division of roles is unclear, there are not enough at-home and community-based services, and the services are not people-centred.

So far, access to specialist medical care services has been seen as the greatest development need in the field. As a result, only people with critical problems tend to reach mental health services. Helping people before they develop critical problems reduces, over time, the number of people who need specialist medical care. Effective and high-quality mental health support services in the community would reduce the demand for higher-level care, but the funding of community-based services in Estonia is fragmented between state authorities, municipalities, and NGOs. The services are temporary and their quality uneven. Mental health problems are often stigmatised, which discourages people from seeking and receiving care.

This article provides an overview of the different types of mental health interventions – supporting activities and services – in Estonia. Describes the problems, development needs, and possible solutions. The underlying premise is that preventing mental health problems is less expensive than treating them, and interventions that support mental health are cost-effective.

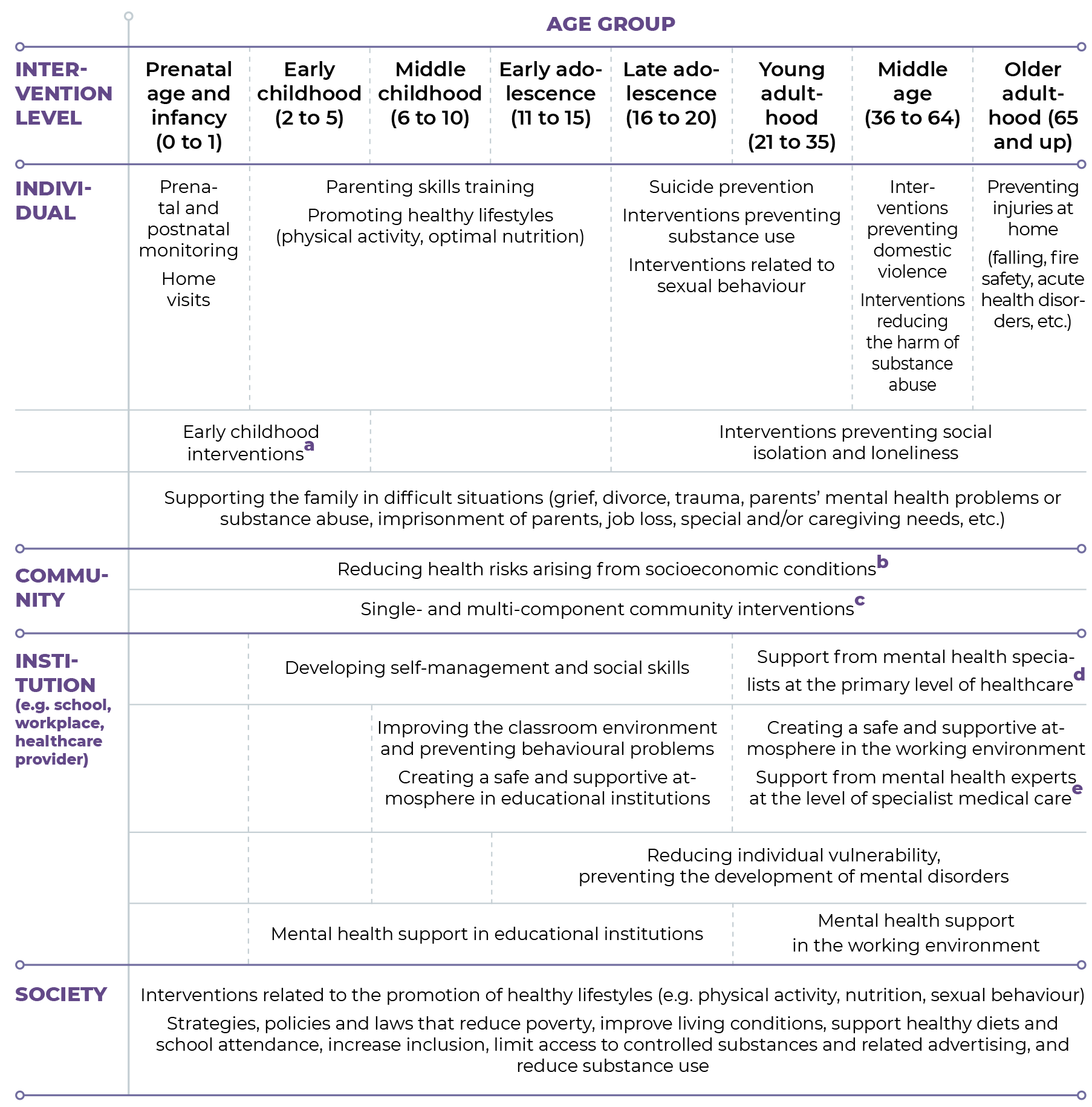

Mental health interventions support people’s wellbeing and prevent mental health problems and their consequences from developing, worsening or recurring. As human behaviour and wellbeing are influenced by individual, social and structural factors. (Barry ja Jenkins 2007), interventions can take place in various environments and be aimed at different target groups (tabel 1.5.1). Supporting mental health begins with adapting the living environment and expanding the available (self-)care options.

Many mental health problems are preventable and can be treated before they reach the healthcare system. If the intervention of a healthcare specialist is necessary, people should get help on the primary level. General practitioners have options for involving mental health specialists, such as referring the patient to a mental health nurse or psychiatric treatment. Various digital solutions support the provision of healthcare services (e.g. e-Health Record, digital prescriptions, remote appointments and e-consultations).

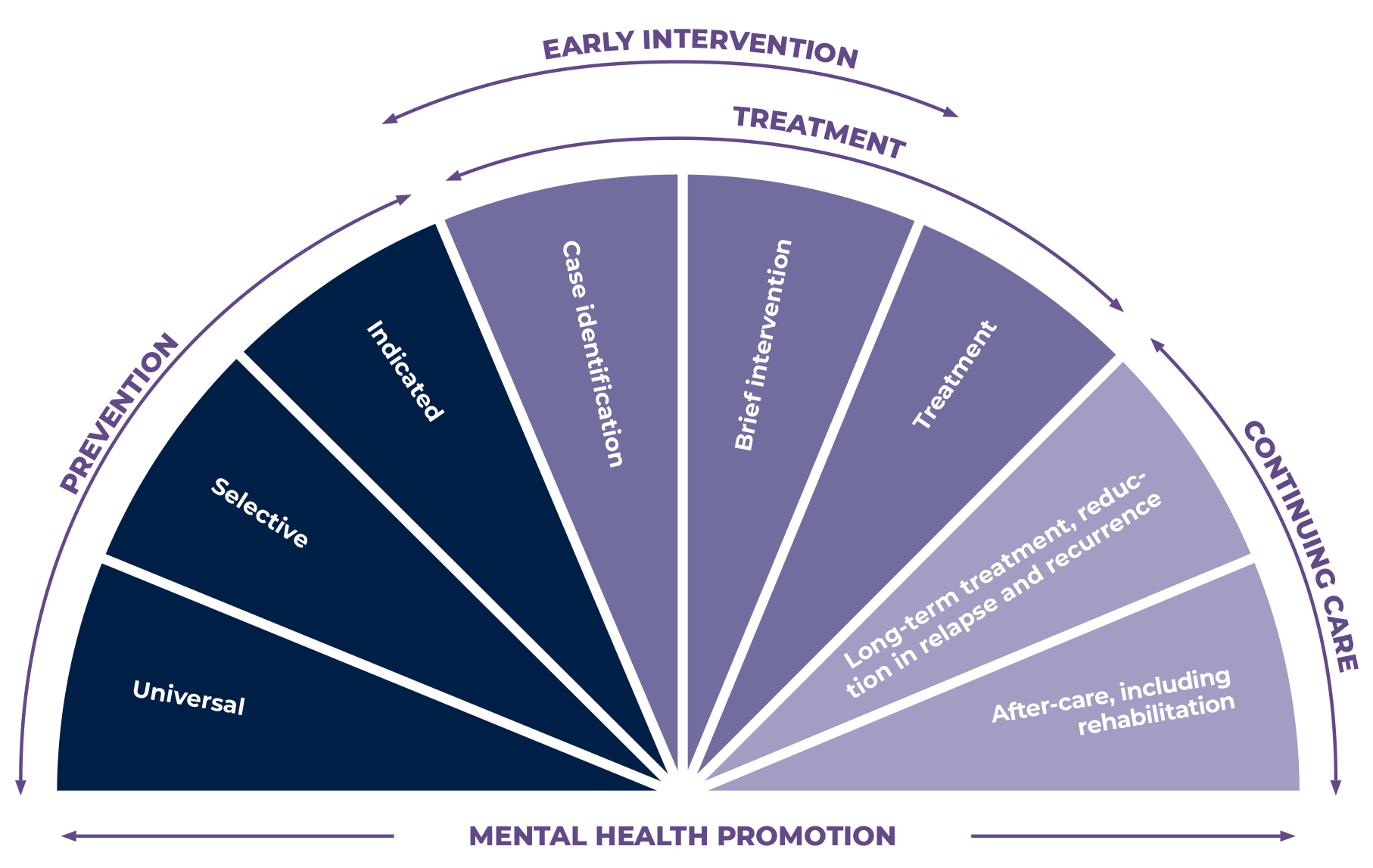

Interventions can be divided into three groups: prevention, treatment and continuing care (Figure 1.5.2). Support networks, community support services and self-care play an important role in all three areas.

Preventive interventions help avoid problems

Preventive interventions help avoid problems emerging or disorders developing throughout life. For example, parents can prevent their child’s mental health problems even before birth by learning about relationship patterns and the child’s development, and monitoring the mother’s mental and physical health during pregnancy. In Estonia, parents can attend family-oriented educational courses, and midwives monitor expectant mothers, but little guidance about changing family relationships is available to parents before childbirth.

Parent-focused interventions (e.g. parenting programmes, family and couples therapy) are effective (Le et al. 2021), but in Estonia they are mostly not free and not accessible to everyone. More than half of Estonian parents have felt that they need help and support in raising their child but either have not known where to get advice or help, or have not dared to ask for it. (Anniste et al. 2018).

Courses for supporting parents in Estonia

- The ‘Incredible Years’ parenting programme is for parents of children aged two to eight years, and other children-raising adults who need support and want to learn how to become better at parenting. The programme takes place over 16 weeks, and small groups meet for weekly sessions lasting 2–2.5 hours. Under the guidance of two experienced instructors and using active learning methods, parents learn how to set boundaries effectively, encourage the child, resolve conflicts, and cope with stress. Childcare is available on-site.

- Gordon Family School’s communication course for parents is intended for parents or adults raising children, and specialists working with parents or children who want to learn more about parenting and family relationships. The programme lasts for eight weeks, and small groups meet for three-hour sessions each week. Using active learning, parents learn about methods for active listening, being assertive, and conflict resolution.

The family supports the child’s mental health during the first years of life. When the child goes to kindergarten or childcare, educational institutions help prevent mental health problems (vt Valk et al. 3. peatükis). Prevention in kindergarten and school means developing age-appropriate social-emotional competence and creating a safe and supportive atmosphere. For example, schools implement the PAX Good Behaviour Game and the KiVa anti-bullying programme, which have been proven to reduce mental health problems. However, not all educational institutions use preventive intervention measures, and the effectiveness and quality of many of the interventions used are unknown. Interventions for vulnerable groups are not accessible to everyone.– Riigikontrolli (2020) audit, only two-thirds of children receive the support services (social pedagogues, school psychologists, special education teachers, speech therapists) they need and that are required by law through educational institutions.).

A special-needs teacher working in an Estonian school on the state of prevention in the field of education:

„We have had very few options for prevention. We are putting out fires because so many of the school staff and students need help.“

The community’s influence in prevention increases during adolescence. For example, alcohol and tobacco policy (including access to substances) affects minors’ substance use, which in turn is influences the emergence of other mental health problems (see Vorobjov et al. in Chapter 2). In adulthood, community-based prevention is reducing loneliness and isolation and supporting social relationships using recreational activities, mental wellbeing support groups, and other similar means.

Notes:a For example, high-quality preschool education that knowingly supports the child’s wellbeing and development; interventions for families at high risk of abuse; and healthcare system based interventions preventing the development and progression of developmental disorders.

b Municipalities offering or mediating support services (including daycare, at-home services and personal care) through social workers, child protection specialists, and others.

c Community intervention measures include psychological counselling (both individually and in groups), support groups, intervention programmes (e.g. ‘Incredible Years’), and others. The content and form of support may vary across support systems. For example, in addition to school psychologists, primary mental health support in educational institutions is provided by teachers, special educational needs coordinators, special education teachers, social pedagogues and others; in a working environment, this is done by (occupational) psychologists, supervisors, and coaches.

d Mental health specialists working at the primary level of healthcare, including mental health nurses and psychologists (e.g. counselling psychologists and unlicensed psychologists working under supervision).

e Mental health specialists working in specialist care, including mental health nurses, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists.

A public health specialist on community-based prevention that supports mental health:

„I think that this kind of involvement or prevention on the community level has a very big impact…I mean the local societies and meet-ups, they should not just be gatherings for dancing and singing. It is possible to bring people together with other objectives as well, and include those who might not otherwise come out on their own … we have been busy with such activites at the moment.“

The working environment influences the mental health of working-age people (see Kovaljov et al. in Chapter 3). In Estonia, prevention aimed at maintaining mental health in the workplace is in its infancy. Some establishments do offer or mediate psychological counselling or training, but there are few long-term systematic solutions that include developing the management’s competence to support mental health in the workplace, involving employees, joint activities, reduced workload and flexible working conditions.

Municipalities and NGOs play a major role in community interventions

In Estonia, mental health interventions (support services and activities) at the municipality and community level have great potential but are underutilised. Local municipalities can facilitate people’s efforts to get help and support early by mediating, for example, hobby clubs, societies and targeted voluntary help and also more formal services, such as counselling and social transport, and by providing access to support groups and intervention programmes. A good example of community support services is psychological counselling that is close to the person’s place of residence. The given municipality has an important role in making such counselling accessible. As of 2021, for the first time, municipalities and primary healthcare centres are able to get financial support from the state to provide psychological care and mental health support services in the community.

Many of the activities promoting and supporting mental health in communities in Estonia have so far been organised by NGOs. But Estonian NGOs’ efforts to promote mental health often lack coordination, not all interventions are equally evidence-based, and the impact assessments are inconsistent. Furthermore, the NGOs’ funding is predominantly project-based, making it harder to prolong even the activities that have proven effective. NGOs in the field are brought together by the Estonian Mental Health and Wellbeing Coalition (VATEK), which deals with both advocacy and policy development in the field and manages the platform enesetunne.ee which offers opportunities for support. There are other great examples of NGOs in the field of mental health membership in VATEK serves as a guarantee of their reliability and ethics .

Online preventive interventions are increasingly being tried out worldwide, but there is still little data on their effectiveness. Various local and nationwide support groups (including virtual groups) exist in Estonia (e.g. there is a support group for parents of children with ADHD and one for the relatives of people with dementia). However, they are not widely known, and funding and the number of seats are limited.

Treatment and continuing care as mental health interventions help people to cope with and recover from problems.

In the event of a health concern or illness, people usually contact their general practitioner and their support team first. PIn addition to the mandatory specialists (family nurse, midwife, physiotherapist), the general practitioner’s support team could also include mental health specialists (mental health nurse, counselling psychologist). If the general practitioner’s team has no mental health specialists, outside experts (clinical psychologists, psychiatrists) can be involved. Minors can be referred to child and youth mental health centres.

General practitioners and their support teams could be the first in the healthcare system to identify mental health problems and risks. They could diagnose and coordinate the treatment of mental disorders and monitor the condition and treatment of patients with chronic diseases to ensure recovery and prevent relapses (Ministry of Social Affairs 2020a).

Primary healthcare centres are currently only recommended to provide mental health services. The willingness of general practitioners and their support teams to treat mental health problems varies greatly from region to region, depending, among other things, on the knowledge and skills of the staff, the availability of tools for assessment and the effectiveness of the cooperating network. The main problems are insufficient preparation and cooperation with mental health specialists. People often cannot get help for their mental health problems from their general practitioner even if they are referred to mental health specialists because there are not enough specialists and waiting times are long.

Many people with mental health problems do not seek specialist care, although getting help at an early stage improves one’s quality of life and saves money. People’s negative attitudes are one of the more significant obstacles to recognising problems and finding solutions. Mental health problems are often stigmatised (Rüsch et al. 2005). Society, for example, holds assumptions about people with mental health problems and seeking help. Individuals might therefore avoid contact with people with mental health problems. In the case of self-stigma, people with a mental health problem might consider their situation shameful and avoid treatment for fear of discrimination and labelling.

Therefore, they only seek help as a last resort, after their situation, daily coping and quality of life have significantly deteriorated.

The Eurobarometer survey conducted in 2006 reveals that Estonians are at the forefront of stigmatising attitudes in the EU. Three-quarters of Estonian residents over the age of 15 considered people with psychological or emotional health problems to be unpredictable (EU average 63%), and 60% considered them a threat to other people (EU average 37%). Nearly a quarter believed that people with mental health problems were themselves to blame for their condition (EU average 14%) and that they would never recover (EU average 21%). Compared to the EU average, Estonian residents less often seek support from a health specialist when feeling bad (40% v. EU average 50%).However, a study published a decade later attitudes have changed somewhat (Ministry of Social Affairs 2016). A significantly smaller proportion of those surveyed believed that people with mental health problems are dangerous (21% of respondents) or that recovering from a mental health problem is not possible (10%). Most respondents in 2016 also agreed that anybody can experience mental health problems (89%) and that mental disorder is a disease like any other (81%). Despite some positive developments, it seems that extensive self-stigma still exists, due to people’s fear of being judged and not wanting others to know about mental health problems (62%). Thus, continued efforts are required to normalise and destigmatise mental health problems in order to encourage people to seek care and improve access to care. At the same time, many people in Estonia also tend to seek support from alternative social media groups (see Tiidenberg et al. in Chapter 4).

The health-supporting choices programme in the Public Health Development Plan 2020–2030 (Ministry of Social Affairs 2020b)outlines the following priorities in mental health interventions:

- development and implementation of evidence-based and consistent mental health policy (including services and networks);

- ensuring sufficient staff for providing mental health support services;

- integration of services and cross-disciplinary cooperation, so that services are accessible and of high quality, based on the needs of the person and consistently supportive of people with mental health problems and their relatives;

- promotion of mental health, including making available evidence-based information, improving health literacy and creating a supportive psychosocial environment.

The main problems of the Estonian health system are the health disparities between socioeconomic groups, poor population coverage, workforce shortages in the health field, and the insufficient management of noncommunicable diseases (Habicht et al. 2018) (Habicht et al. 2018). According to the 2020–2022 data of the Estonian National Mental Health Study, people with no or very low income visit mental health specialists significantly less often than people with higher income, although they do not have fewer subjective complaints. This indicates that access to services in this population group is limited (Estonian Population Mental Health Survey Consortium 2022).

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Mental Health Atlas 2005 pointed out that the burden of mental health problems on healthcare systems has increased, while funding treatment has not increased proportionally and tends to go towards specialist medical care in large hospitals. Although progress has been made in several key areas over the past 20 years, the availability of mental health resources continues to be unequal between countries with different standards of living, and within countries. The WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020 indicates that limited access to mental health resources at the primary healthcare level is particularly conspicuous.

Everyone has the right to access the services they need in a timely manner.

However, Estonia has an extensive shortage of mental health specialists (Ministry of Social Affairs 2020a). In 2019, there were 30–50% fewer school psychologists, and 50% fewer clinical psychologists and mental health nurses, than optimal. PWith the need to step up the capacity to help with mental health concerns at the primary healthcare level the shortage of professional psychologists (counselling psychologists, clinical psychologists and mental health nurses will increase by about 10% in the near future.

Access to non-hospital psychiatric care is central to care planning. The labour shortage in psychiatry, and especially in child psychiatry, has been constantly increasing. Based on OECD data, Estonia should have a ratio of 14 to 24 psychiatrists per 100,000 inhabitants(OECD 2021According to the National Institute for Health Development 28 psychiatrists were working in Estonia in 2019, including 24 child and adolescent psychiatrists, accounting for 16 psychiatrists per 100,000 inhabitants. However, the Estonian Psychiatric Association’s development plan for the field of psychiatry places the recommended level at 260 psychiatrists, or 30 to 40 more than there currently are. Many psychiatrists are of or will soon reach retirement age.

Although the number of psychiatrists in Estonia is just above the lower limit proposed by the OECD, it does not cover the current demand and is far below the level of the Nordic countries and other countries with a high level of welfare (e.g. Finland, Sweden and Germany 20 or more psychiatrists per 100,000 inhabitants).

Suboptimal use of specialist care (e.g. for activities that could be carried out in primary care) leads to overtime work and persistently long waiting times. The actual availability of psychiatrists is, therefore, smaller than the ratio suggests.

Working-age people with depression on the accessibility of services:

„I saw a psychiatrist eight to nine months after my initial visit to the general practitioner.“

„It was difficult to find help in the beginning. I ended up seeing a psychiatrist three to four years later.“

„The psychiatrist didn’t have any available psychologists to recommend.“

„The general practice should have had a mental health nurse.“

„You should be able to see a psychologist thanks to the Therapy Fund. It’s another dead end, because they are not accepting new patients – [they say to] try again in a while.“

„There are no support groups. The support network should be bigger. There is no one to support me.“

More resources alone will not necessarily lead to the desired changes, including reduced waiting times, higher quality of treatment or better outcomes. Currently, Estonian general practitioners can use the funding mechanism created for this purpose – the Therapy Fund – to refer people to specialists, such as clinical psychologists. However, this resource is underutilised. For example, in 2020, general practitioners used only 38% of the funds on average. In 2021, that figure was 44% on average. Bureaucratic barriers in the organisation of the Therapy Fund, a lack of knowledge among general practitioners about various mental healthcare options, and a lack of care options make access to services problematic.

In order to have an efficient mental health services system in Estonia, the funding model of healthcare services has to be restructured (Vainre et al. 2021). One of the important factors to consider is the availability of specialists with appropriate training, competencies and qualifications, which require increased volumes of national training. However, increasing the number of specialists is only part of the overall solution. Mental health problems stand on a continuum – from temporary conditions to highly disturbing chronic diseases, from single problems to clusters of disorders. These conditions require interventions of varying intensity.

People need to have access to the lowest-intensity support necessary and effective for their condition. In Estonia, the main problem seems to be how to provide a suitable service for people in need. There are few easily accessible and low-intensity community-based mental health support services and psychosocial interventions offered in Estonia, although their wider availability could shorten waiting times and improve the overall quality of mental health services. It would also help ensure better access to specialist psychiatric care for people who need intensive intervention.

A network to fight depression: a four-level community-based intervention approach

EAAD (European Alliance Against Depression) is an intervention model aimed at preventing suicidal behaviour in the community through early recognition and optimal treatment of depression. Optimal treatment is a mix of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, which can be integrated with the guided online self-management programme iFightDepression® (www.ifightdepression.com/en). What makes EAAD unique is the synergy of simultaneous interventions at four levels:.

- Primary-care practitioners (e.g. general practitioners and family nurses), who receive training to recognise and treat mild and moderate depression.

- The general public, educated with depression awareness campaigns, with the media helping to reduce stigmatisation and promote seeking help.

- „Gatekeepers“ (e.g. social workers, teachers, police), who can recognise depression early and refer people to care.

- Patients, their relatives and high-risk groups (e.g. people who have attempted suicide or lost a relative due to suicide), whose recovery can be helped with support groups and information materials.

EAAD is one of the more promising multi-level intervention models. References to the evidence base are available on the project’s website. In Estonia, a network for coping with depression based in Pärnu has implemented the EAAD model since 2021. (www.depressioonigatoimetulek.ee).

E-health solutions (electronic health records, telemedicine, digital solutions) are both a challenge and an opportunity for the Estonian healthcare system. They should be applied more effectively in the provision and integration of services and in clinical decision-making (Habicht et al. 2018). Both recipients and providers of the services must adapt to the new solutions, including remote services. As with any other mental health service, digital solutions have to be evidence-based, efficient, high-quality, cost-effective and accessible.

In recent years, the funding of healthcare system development projects has increased. It includes, among other things, people-centred care pathways and remote services. The conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic confirmed that both mental health service providers and users are able to use remote services in a crisis situation. The Estonian Health Insurance Fund facilitated this, financing remote appointments (since March 2020) and remote therapy (since November 2020). As a result of the changes made in the healthcare system during the COVID-19 crisis, the share of remote appointments with psychiatrists increased significantly (from 20% to 38%). The share of remote appointments and remote therapy sessions with mental health nurses and clinical psychologists increased as well (from 13% to 24%). People with a chronic mental health disorder should first contact mental health nurses in the healthcare system. Mental health nurses could benefit from remote appointments. When the patient consents, nurses could use digital solutions to collect and analyse health data and forward it to a specialist in a form agreed on in advance.

Mental health disorders bear high costs for the healthcare system, and first-time cases are generally more expensive to treat than recurring ones. Promoting mental health and preventing problems is effective for the people affected, their relatives and society, but the incentives to invest in it are still too limited. (Le et al. 2021).

From the position of society, it is important to consider two types of costs:

- direct costs to the healthcare and social system, including medical expenses and social welfare expenses due to reduced work capacity;

- indirect costs associated with reduced tax revenue, as reduced work capacity and coping may decrease or even eliminate income.

Depression, which is one of the most common mental health disorders, is a good example of costs related to the treatment of mental health disorders (see Akkermann et al. in this chapter). The analysis of the care pathway of depression (Randver 2021) revealed that the direct cost to the Estonian Health Insurance Fund of treating a two-month episode of depression is approximately 300 euros for the first case of depression and approximately 200 euros in the case of recurring depression. First cases undergo more diagnostic procedures (analyses, examinations) than recurring cases, where less time is required for assessment, choosing an intervention and initiating it. The cost of longer treatments has increased. The annual treatment cost of a first episode of depression is approximately 800 euros, and for recurring depressive disorder, it is approximately 500 euros. Thus, preventing new clinical cases from occurring is the most cost-effective.

Between 2013 and 2020, the annual cost of treatment for first-episode depression (primary diagnosis) in Estonia has increased sharply, from 2 million to more than 6 million euros. For recurring depressive disorder, the figure increased from 2 million to 5 million euros. The cost of incapacity for work benefits has also increased: in the case of first-episode depression, it was less than 1 million euros in 2014 but over 2 million in 2020. RThe costs related to prescription medicines for both the patient and the Estonian Health Insurance Fund remained relatively stable between 2005 and 2020.

A 2021 study on the prevalence and economic impact of treatment-resistant and suicidal depression also shows that depression carries significant costs. Anspal and Sõmer 2021) The cost of suicides in patients with depression was calculated based on the value of statistical life, as recommended by the OECD, which is based on people’s willingness to trade off income for risk reduction(OECD 2012). Transferring the value recommended by the OECD to Estonian price levels in 2020, the calculated average cost of a suicide case was 4.6 million euros. This includes the economic cost for the state and the individual, as well as the loss of wellbeing in general.

Preventing mental health problems is more cost-effective than treating them, and treating the problems is more cost-effective than leaving them untreated. Each euro invested in prevention can save between 5 and 50 euros in the future, depending on the intervention (WSIPP 2019).

Despite this, access to preventive interventions is limited in Estonia; the interventions are not implemented systematically, and their impact is mostly not assessed.

In addition to limited access to preventive interventions, the care pathways of people with mental health problems are fragmented, complex and under-resourced. Interventions provided by the support systems should be better balanced with people’s specific needs. While ensuring that the interventions are accessible, targeted and of high quality.

Reducing stigmatisation and increasing early detection and prevention requires improving people’s social-emotional and self-care skills, extensively implementing effective interventions, creating safer and more supportive environments to enhance social cohesion, simplifying care pathways, and upgrading the accessibility and consistency of care options.

Anniste, K., Biin, H., Osila, L., Koppel, K., & Aaben, L. (2018). Lapse õiguste ja vanemluse uuring 2018. Uuringu aruanne. Tallinn: Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis. Kättesaadav: https://www.praxis.ee/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Lapsed-vanemad-aruanne.pdf

Anspal, S. & Sõmer, M. (2021). Raviresistentse ja suitsiidse depressiooni levimus ning majanduslik mõju. Eesti Rakendusuuringute Keskus CENTAR. Kättesaadav: https://centar.ee/tehtud-tood/raviresistentse-ja-suitsiidse-depressiooni-levimus-ning-majanduslik-moju

Barry, M. M., & Jenkins, R. (2007). Implementing Mental Health Promotion. Springer Nature.

Eesti rahvastiku vaimse tervise uuringu konsortsium (2022). Eesti rahvastiku vaimse tervise uuringu lõpparuanne. Tallinn, Tartu: Tervise Arengu Instituut, Tartu Ülikool. https://www.tai.ee/et/rvtu

Habicht, T., Reinap, M., Kasekamp, K., Sikkut, R., Aaben, L. & Ewout, V. G. (2018). Estonia: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition, 20(1): 1-193

Haggerty, R. J., & Mrazek, P. J. (Eds.). (1994). Economic Issues. In Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research, 405-414. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

Le, L. K.-D., Esturas, A. C., Mihalopoulos, C., Chiotelis, O., Bucholc, J., Chatterton, M. L., & Engel, L. (2021). Cost-effectiveness evidence of mental health prevention and promotion interventions: A systematic review of economic evaluations. PLoS Medicine, 18(5), e1003606. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003606

OECD (2012). Mortality Risk Valuation in Environment, Health and Transport Policies. Kättesaadav: https://www.oecd.org/environment/mortalityriskvaluationinenvironmenthealthandtransportpolicies.htm

OECD. (2021). A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health. OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6-en

Randver, R. (2021). Depressiooniga tööealise inimese raviteekonna kaardistamine ja analüüs. Lõppraport. Eesti Haigekassa. Kättesaadav: https://www.haigekassa.ee/partnerile/raviasutusele/depressiooni-raviteekond.

Riigikontroll. (2020). Hariduse tugiteenuste kättesaadavus. Kättesaadav: https://www.riigikontroll.ee/tabid/206/Audit/2516/language/et-EE/Default.aspx.

Rüsch, N., Angermeyer, M. C., & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539.

Sisask, M., Kõlves, K., & Hegerl, U. (2021). Intervention studies in suicide research. In K. Kõlves, M. Sisask, P. Värnik, A. Värnik, & D. De Leo (Eds.), Advancing Suicide Research (pp. 99–120). Hogrefe Publishing.

Sotsiaalministeerium (2016). Elanikkonna küsitlus: Elanikkonna teadlikkus, suhtumine ja hoiakud vaimse tervise teemal. Kättesaadav: https://www.sm.ee/sites/default/files/content-editors/eesmargid_ja_tegevused/Norra_toetused/Rahvatervise_programm/elanikkonna_teadlikkus_suhtumine_ja_hoiakud_vaimse_tervise_teemadel_2016.pdf.

Sotsiaalministeerium (2020a). Vaimse tervise roheline raamat. Kättesaadav: https://www.sm.ee/media/1345/download.

Sotsiaalministeerium. (2020b). Rahvastiku tervise arengukava 2020-2030. Kättesaadav: https://www.sm.ee/rahvastiku-tervise-arengukava-2020-2030.

Steel, Z., Marnane, C., Iranpour, C., Chey, T., Jackson, J. W., Patel, V., & Silove, D. (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476-493.

Streimann, K. (2019). Riskikäitumise ennetamine paikkonnas. Rahvatervise spetsialistide rühmaintervjuude kokkuvõte. Tallinn: Tervise Arengu Instituut. Kättesaadav: https://www.tai.ee/sites/default/files/2021-03/157355322514_Riskikaitumise_ennetamine_paikkonnas.pdf.

Streimann, K., & Vilms, T. (2021). Vaimse tervise probleemide ennetus koolis. Harjumaa koolide tugispetsialistide ja koolijuhtide rühmaintervjuude kokkuvõte. Tallinn: Harjumaa Omavalitsuste Liit. Kättesaadav: https://www.hol.ee/docs/hol%20vaimne%20tervis_1.pdf.

Vainre, M., Akkermann, K., Laido, Z., Veldre, V., & Randväli, A. (2021). Kroonviiruse epideemia psühhosotsiaalsete tagajärgedega toimetulek. Tallinn: Sotsiaalministeerium. Kättesaadav: https://www.sm.ee/media/2128/download.

WSIPP (2019). Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Benefit-cost results. Kättesaadav: https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost