Mental health stories from the past: Where do we come from?

For centuries, opinions have been voiced about the health of Estonian minds. First it was by strangers, who saw the local people as an object of study. And then it was by the Estonians themselves, who formulated their views on the matter in the late 19th century. This period, commonly known as the Age of Awakening, saw imported scientific ideas intersect with the emerging Estonian elite’s inferiority complexes and burgeoning national ambitions. The question of Estonians’ mental health emerged in various contexts, some examples of which are presented below.

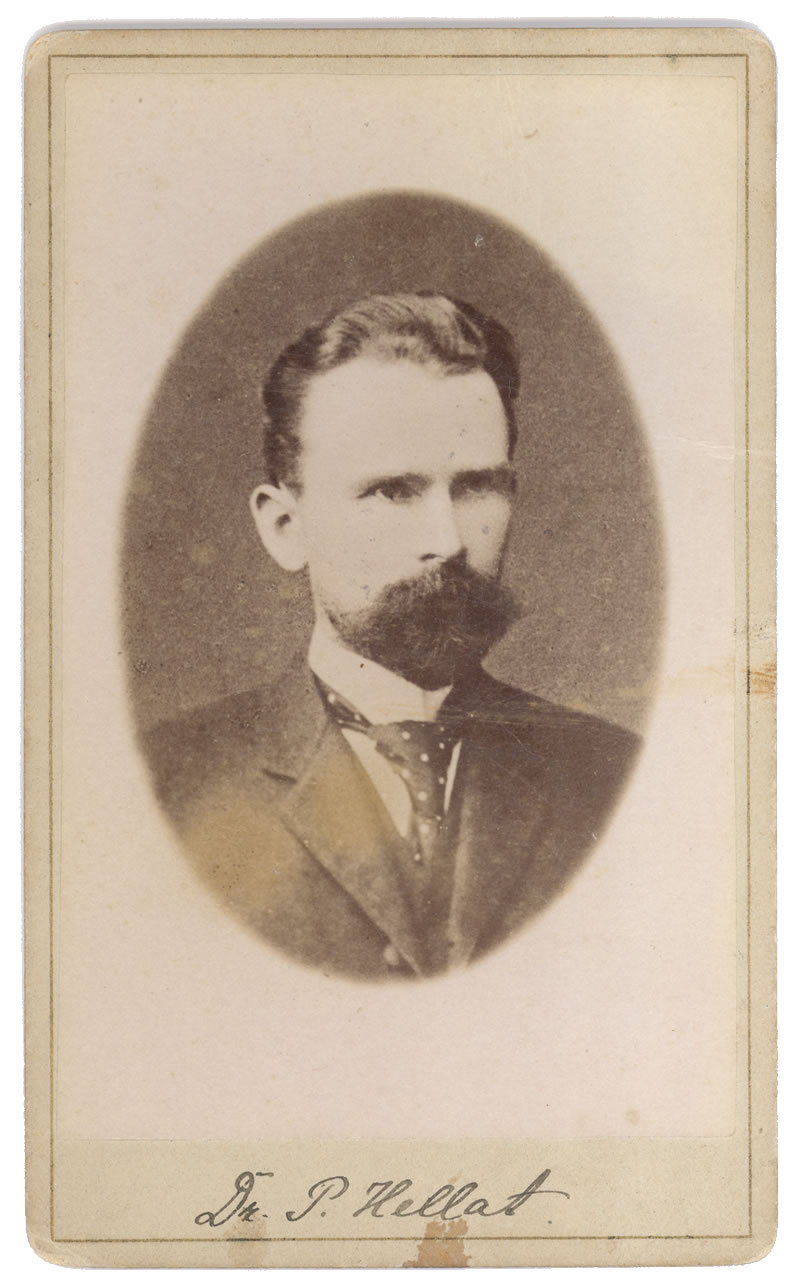

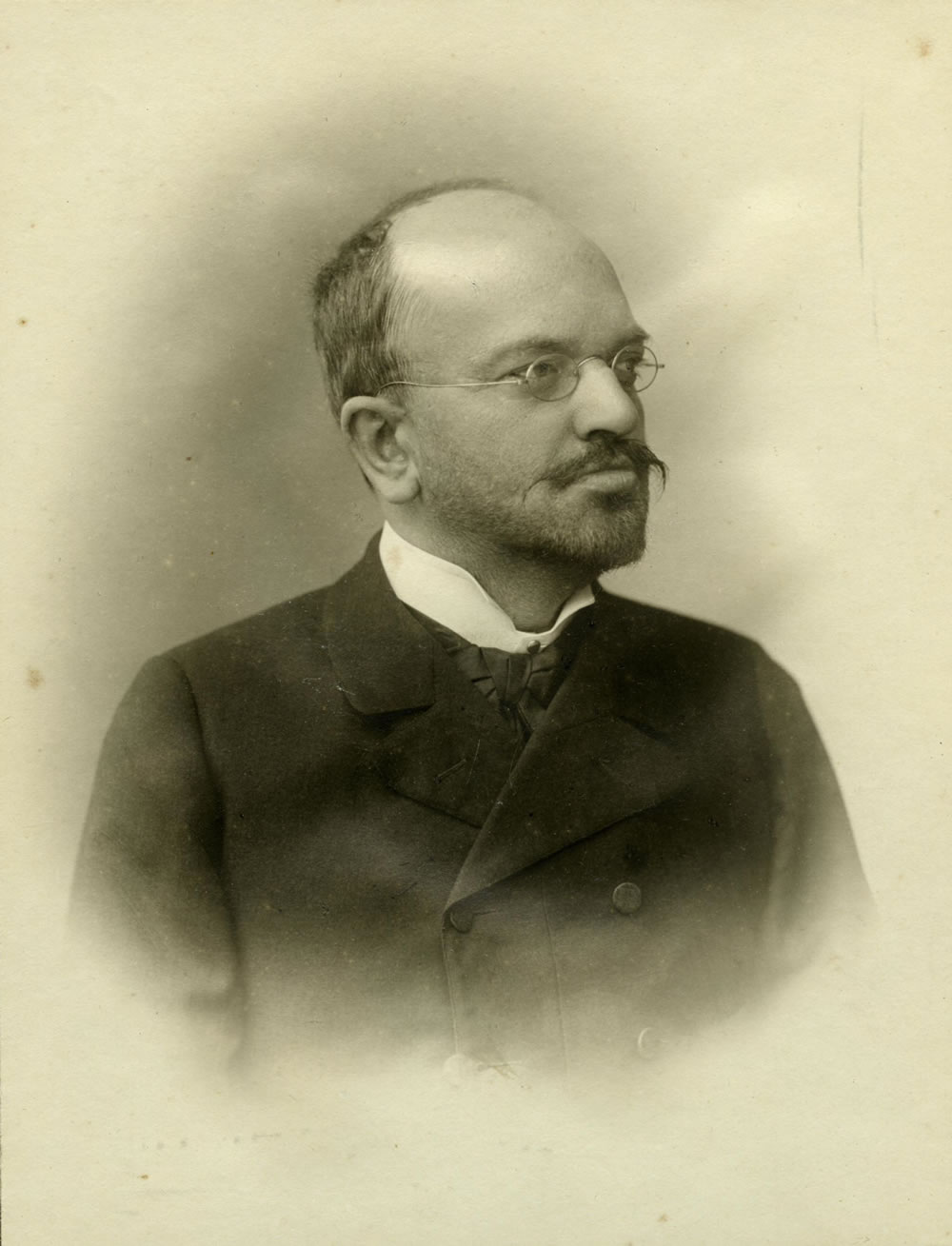

Two hundred years ago, Baltic German scientist Karl Ernst von Baer thought that mental illness was uncommon among Estonians: ‘This demonstrates the extent to which a cultured and refined way of life, a dangerously heightened imagination, and education, by sharpening sensibilities, contribute to the development of these diseases.’ Soon, however, the situation changed, as Estonians gradually gained new rights and liberties and embarked on the course of national awakening. At the beginning of the 20th century, Estonian doctors Peeter Hellat and Juhan Luiga diagnosed many of their compatriots with a condition they called hysteria estonica. It was thought to be the ‘malady of foreign ways’, the kind that strikes those who have abandoned their traditional way of life. We see a parallel here with the labelling of women’s emancipation, which was similarly centred on the concept of hysteria.

Another condition believed to be widespread among the population was neurasthenia estonica, supposedly caused by the mental and physical stress related to urbanisation, the spread of school education, and so on.

These consequences of national emancipation, it was believed, hit the elite the hardest. In 1920, doctor Juhan Vilms wrote that to solve this problem, the whole nation needed to rise to a higher cultural plane, because then “the burden of work would rest on everyone’s shoulders”.

Until that happened, the self-sacrificing efforts of a handful of intellectuals would lead to “physical and nervous weakness, and therefore also limit the prospects of future generations, for it is known that intense physical and mental work has a dampening effect on sexual functions”. In 1940, the anthropologist Juhan Aul complained that city children were being pampered by the lack of physical work while being trained by their ambitious parents “beyond the natural course of mental development, including by taking all kinds of lessons”.

The fear of tuberculosis and impaired vision were therefore not the only reasons for recommendations to shorten the period of schooling. In 1912, Marta Reichenbach-Riikoja, who later became a writer and translator, wrote: “Mothers who have crooked spines, narrow hips and sagging breasts from sitting too much in school at a young age, who suffer from permanent fatigue and boredom with life – mothers such as these are what destroys our nation.” In the same year, writer and manor owner Peeter Lensin saw women’s secondary education as guilty of fostering ambitions that could never be fulfilled, claiming it only produced women who were destined to end up as prostitutes or wander from one “meeting” to the next. (The latter was an allusion to political activism.) Lensin, who believed that fulfilling a mother’s role came first, maintained that learning housekeeping skills was all the training women needed.

His argument was that the average female brain was smaller than the average male brain. The implication was that it was not as well adapted to the stresses of learning.

It was clear that history and circumstances had not been kind to Estonians. When it came to discussions about mental health, however, some wondered whether, in addition to the external circumstances that shaped Estonians’ character and diagnoses, part of our mental health was also shaped by our ‘racial’ attributes. Baer, who believed that the majority of Estonians were phlegmatic and the minority melancholic, spoke in the 19th century about rural people’s cruelty toward the weak. A century later, Vladimir Chizh, professor of psychiatry at the University of Tartu, compared the criminal behaviour of Latvians and Estonians and believed that the latter were more violent.

He claimed that even the most trivial quarrels among Estonians could end in murder. The rate of infanticide was also higher among Estonians, and it was tempting to ascribe this to the lack of communal empathy shown towards unmarried mothers (the ones typically responsible for this type of crime).

Chizh, who maintained that Estonians and Latvians belonged to different ‘races’, believed that his work had demonstrated that criminality was an innate vice. Such biological determinism was difficult to accept for Estonian thinkers, who had to trust in the possibility of change by, for example, fostering a more caring society.

In 1913, doctor Peeter Hellat wrote that the spiritual life of Estonians could take a turn for the better only after “our people rid themselves of another rudiment of perpetual agony and darkness: the beating of children”. Hellat believed that any kind of violence robs the nation of a future because “a weak plant that grew under such conditions snaps and withers more easily under the depravities and hardships of life”. Hellat also wrote: “We have no yardstick for measuring to what extent thousands of years of violence against women has eroded the strength, health and mental reach of humanity.” Hellat was referring to injustice against women in general, but today his remarks call to mind issues of domestic violence and alcohol abuse.

The temperance movement emerged as one of the central components of Estonian nationalism by the end of the 19th century, mainly because alcohol abuse was believed to contribute to the extinction of small nations.

Psychiatrist Juhan Luiga wrote in 1910: „Only degenerate nations can disappear.“ In 1922, educator Peeter Põld asserted: “Even moderate alcohol consumption in parents – and this has been scientifically established without dispute – increases sickliness, dullness, sluggishness and various nervous diseases among children that lead to ruination and decrepitude.” Thus, in addition to hindering population growth, alcohol was also seen as an obstacle to edification.

Considerations of the population’s health and quality, or ideas of “breed improvement”, caused the temperance movement to branch out into the eugenics movement in Estonia. The members of the Eugenics Society, founded in 1924, believed that: “A nation can survive in the struggle for existence only if it contains the most people possible who are endowed with good physical and mental qualities, character and moral strength.”” Eugenics overstated the role of heredity: “The abilities of both a normal person and a genius are predetermined by heredity; this is the great destiny that determines the path and accomplishments of each person.’ Mental disorders were believed to be primarily hereditary (congenital), and experience showed that in most cases, they were also incurable (this was before the pharmacological revolution). And so there were efforts to limit the reproductive capacity of people with psychiatric diagnoses. This was facilitated by the law enabling forced sterilisation that came into force in 1937.

Regrettably, heredity was also associated with areas of life in which biological determinism is not recognised today, and psychiatric diagnoses were often misapplied. For instance, economic considerations were used as a pretext in calls to limit ‘the number of feeble-minded children of feeble-minded unmarried mothers, all of whom remain in the care of society’. Terms such as ‘unmarried’ and ‘number of children’ were enough to elicit a diagnosis…

However, social policy carried out via the surgeon’s scalpel was seen as an extreme position. The same can be said about eugenic views whose proponents suggested leaving some areas of mental health (such as alcoholism and suicide) to “natural selection”. Finding the right diagnosis was not considered enough to improve the situation; the root cause of the problems was sought.

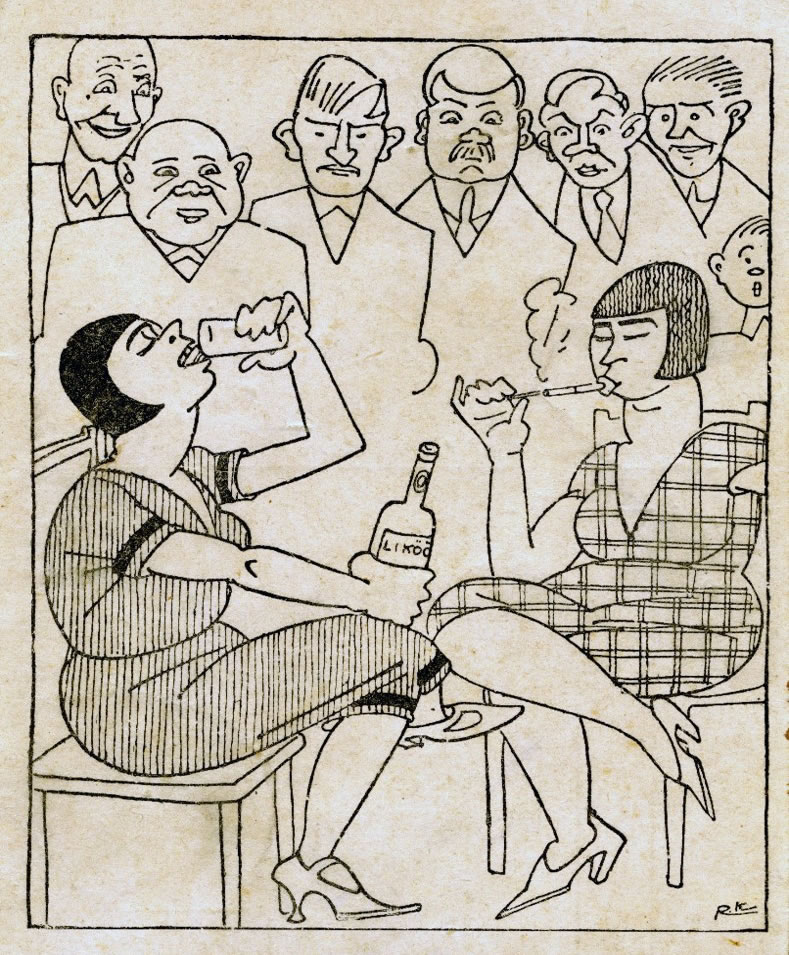

The above examples of the ‘nature versus nurture’ debate in determining the root cause are characteristic of an era in which pharmacological capacity to improve mental health was still in its infancy and a healthcare and welfare system like the one we have today was far from being a reality. Alongside eugenic theories, there were moralising positions that saw “pleasure culture” as a threat to mental health. But there were also those with a more realistic mindset. The Estonian Mental Health Association was founded in 1932 with the position that “Many illnesses stem from worries, misery and humiliation.”” Both lines of thought are still alive today, with molecular biology having replaced eugenics.

An example of the instruments used by the temperance movement in Estonia in the first half of the 20th century

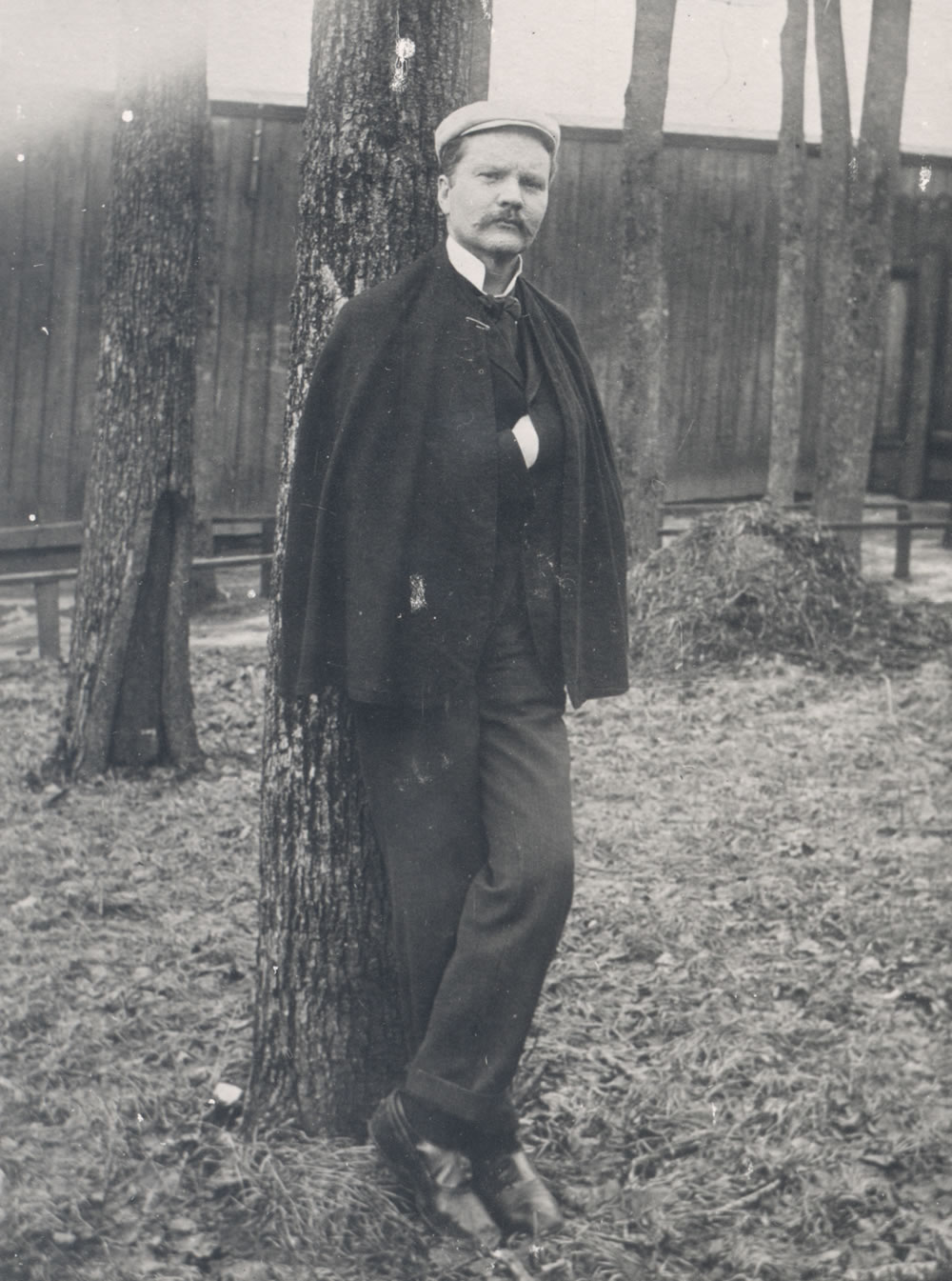

What modern-day Estonia has in common with 20th-century interwar Estonia is that the nation is free. Writing before Estonia became independent, Juhan Luiga lamented that ‘we are tormented by nightmares on either side’, referring to the German and Russian oppressors in our history. Today, we must work to overcome our own nightmares.